Submit a Bay Area climate change question for KQED’s science reporters at the bottom of this post.

It’s getting hotter. It’s getting smokier. It’s getting scarier.

California’s extreme droughts, heat waves and wildfires will likely worsen in the coming decades and longer if we don’t get our act together.

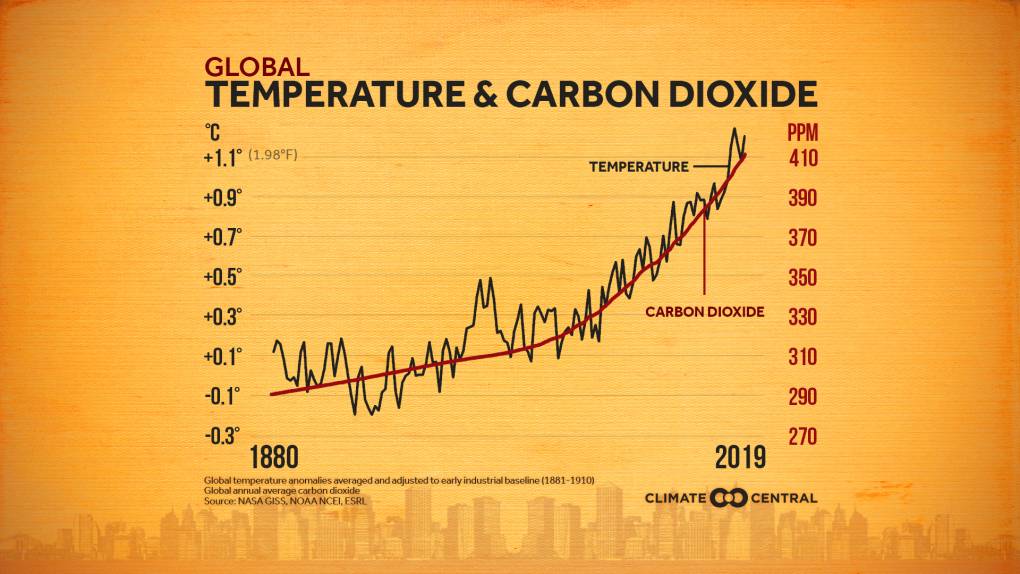

The concentration of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere is greater than any time in at least the past three million years, and the world has already warmed 2 degrees Fahrenheit (1.1 degrees Celsius) since the 1800s.

People of color are and will be disproportionately affected by the health and environmental impacts of climate change, according to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

Taking all this in is overwhelming. But here’s something that makes it easier: there is still time to act.

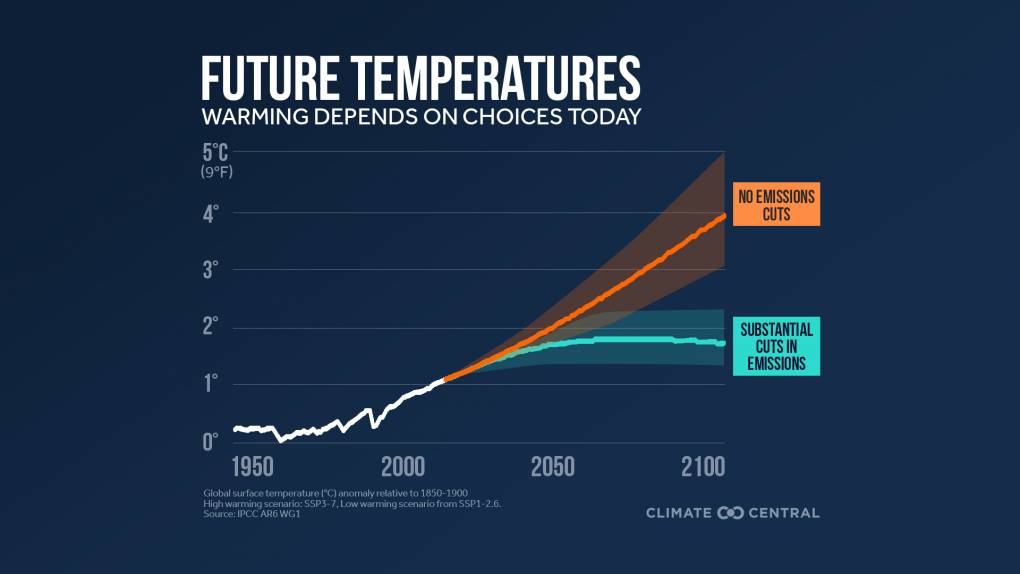

Rapid, bold emissions reductions, starting now, would limit climate change and its effects.

We decide what future we get. The one that will be recognizable to us, with limited warming, would require coordination across communities, states and countries.

While limiting warming to 2.7 degrees Fahrenheit (1.5 degrees Celsius) would be “very difficult, requiring immediate, top-level government attention and effort,” said Michael Oppenheimer, a Princeton environmental scientist and editor of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change review, it’s “not impossible.”

Even if we don’t meet those goals, Oppenheimer said, “there’s no end-of-the-world point where you give up.” Every tenth of a degree matters.

That’s where you come in. Climate scientists made it crystal clear in the U.N.’s most recent report that warming is a “code red for humanity,” according to U.N. Secretary-General António Guterres.

This piece is for those who want to respond, but don’t know where to begin.

All of us

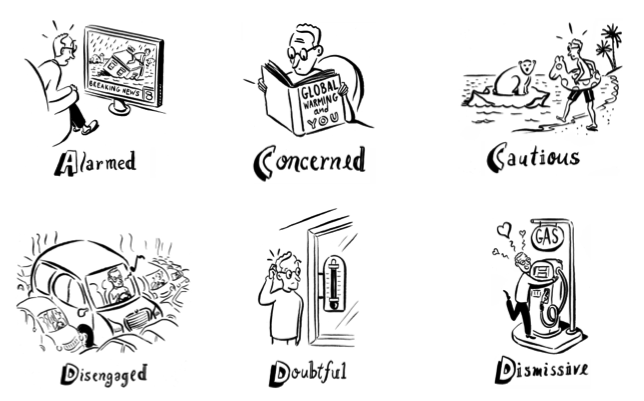

Maybe you think we’re in two camps here in California: those who believe in climate change and those who don’t. But researchers define us with more nuance.

The Yale Program on Climate Change Communication divides Americans into six groups: from those deeply concerned about global warming and supportive of policies (“Alarmed”), to those who view it as a hoax (“Dismissive”).

More than half of people in the U.S. fall into the “Alarmed” or “Concerned” categories. This means they’re engaged in this issue and ready to act.

Most of these folks don’t know what to do with that worry, though, or how to take meaningful action on climate.

Let’s feel some feelings

Longtime Bay Area residents will recall a time when the weather didn’t whiplash from bone dry to flooded streets, when skies choked with wildfire smoke were anomalous and average fall temperatures were cooler (by 3 degrees Fahrenheit in San Francisco, to be precise). If you’re a recent Bay Area transplant, I imagine you can think of similar changes wherever you hail from.

Facing the climate crisis means grieving the version of the planet we grew up with. That means sitting with painful emotions.

The sadness, despair, anger and powerlessness are normal, healthy responses to a serious risk.

“We are biologically wired to respond with anxiety to real threats,” said Robin Cooper, a San Francisco-based therapist and founder of the Climate Psychiatry Alliance.

Resisting these feelings is normal too — it’s a means of protecting ourselves. But burying our heads in the sand ultimately leads to the same outcomes as denying the crisis. Take breaks, but face what is happening. At some point it becomes easier to look at the issue than hide from it.

Finally, let yourself feel things. There are losses we cannot reverse. There will be more.

Feeling the hard emotions lets you move through them and forward. That doesn’t mean you’re free of them — you aren’t, but pushing them down won’t help you move into action.

Here are some ways to process your emotions, since a lot of us are out of practice:

- Connect with people. Talk informally with family or friends, or more formally with a therapist (there are growing networks of psychiatrists and psychologists with specific training on climate change), or grief groups.

- Connect with your body through walking, running, yoga, or any exercise you enjoy.

- Connect with nature. Environmental psychologist Renee Lertzman said getting out in nature is both calming and “reminds me of why we’re doing this. I’m continually amazed by how incredible life is.”

There are plenty of other articles, books, and podcasts about processing these heavy emotions, too.

Imagine the future you want

It’s inspiring to envision a Bay Area less dependent on fossil fuels, with cleaner air, more predictable weather cycles, and a booming green jobs industry.

Air pollution from fossil fuels affects low-income communities and communities of color far more than others, in places close to freeways and industry, like East and West Oakland.

Studies from Oxfam show the poorest 50% of Americans are responsible for far less carbon pollution than the average American — about half. Cleaning up our climate is an act of equity.

Cutting down fossil fuels would save lives. California’s air regulator estimated that we see 7,200 premature deaths each year from air pollution, particularly from pollution related to diesel exhaust.

Globally, air pollution from burning fossil fuels is responsible for 8.7 million deaths annually, shaking out to more than a tenth of U.S. deaths (deaths from COVID-19 stand at nearly 5 million people globally since the start of the pandemic).

The average life expectancy would increase by more than a year across a world without fossil fuel emissions.

Switching out gas appliances like stoves for electric ones significantly improves indoor air quality, which could lead to lower risk for cardiovascular disease in adults and asthma in children.

As many of us experienced during the pandemic, converting streets into places for communities to gather brought a lot of joy, with “slow streets” and increased outdoor dining. San Francisco voters decided to make some of these car-free streets permanent. Should our cities build out a more walkable and bikeable infrastructure, this could be our norm.

Climate action could be a boon for green jobs, like those installing solar panels and restoring wetlands.

And climate progress could significantly impact our mental health. That’s because the antidote to climate anxiety is action.

Act

You do not need to become anything you are not to take action on climate change. The issue is big, and the good part about that is there are endless ways to plug in.

Climate scientist Kim Nicholas says consider where you spend most of your time and where you get the most energy right now. Start there. Ask yourself, “how is it that we as a family, as a business, [or] as a neighborhood, are impacting the climate? What is it that we can do?”

While climate activists debate whether to push people to organize for systemic change or focus on individual actuals, they tend to agree that both are needed. Systems need transforming and the largest reductions in emissions will be found there. But individual changes — especially in rich countries like the U.S. — are important, too.

Action at the systems level

Find a group that works for you: Climate journalist and organizer Bill McKibben says the most powerful thing an individual can do is be less of an individual. Your voice will be more powerful with others, and it’s more fun and hopeful to tackle this challenge together. There’s no shortage of groups of people concerned about the climate and taking meaningful action.

There are groups for skiers, nurses, artists, political conservatives, grandmothers, hunters, and people concerned with national security. See the range? Groups such as these can help guide you to advocate for more change at the systems level.

Vote for climate candidates: The rapid policy reform needed to address the climate crisis requires politicians to enact bolder, faster changes.

Research shows electing representatives that ranked high on the League of Conservation Voters National Environmental Scorecard significantly reduced a state’s carbon dioxide emissions.

Voting female politicians into office is linked with stronger climate policies and lower emissions, and could be an underutilized tool.

Contact your representatives: Call your local, state or federal representative to share your concerns. Sure, there are other ways to get in touch too, like email and snail mail, but activists and lawmakers say the best way to grab a staffer’s attention is to call and not email, The New York Times reports.

If your representatives already share your beliefs, thank them for their efforts and ask them to move further or faster.

Action at the individual level

While the numbers show that minimizing your carbon footprint won’t get us where we need to go on greenhouse gas reductions alone, “If you live in a rich country, and especially the richer you are, your individual actions really matter,” sustainability scientist Kimberly Nicholas writes in her book “Under the Sky We Make.”

Personal climate actions like skipping drives and flights matter in both reducing carbon, and in changing the perception of a wealthy American ideal — using excessive carbon — that’s quickly getting exported.

When changes become a social norm, it becomes more attractive for politicians and companies to take action. Research shows just 25% of a population is needed to create a norm change.

Our suggestions reflect actions shown to have the biggest impact, so you can spend your limited time and brain capacity judiciously, though there are plenty of other worthwhile things to do.

Talk about climate change: While the majority of Americans are worried about climate change, most people don’t talk about it, even if they’d like to, says Anthony Leiserowitz, director of Yale’s climate communication program. He says by avoiding talking about the topic, we fail to signal how much it matters to us.

Climate scientist Katharine Hayhoe has had thousands of conversations about climate change. She recommends a helpful formula for your discussion: start with what you both care about (like your kids, the beach, birds, etc.), connect that passion with climate change (climate change affects everything, so luckily that’s not hard), and then discuss what’s at stake for what you love, and some solutions that are at work locally.

You can also talk about what you’re doing about climate change (no self-righteousness please though, that won’t help your cause). Lots of folks are changing their behavior based on the climate crisis, and sharing that could contribute to societal shifts. There are tools to help your community, company, or place of worship collaborate, or even compete with one another.

Yale’s climate change communication program has tips on how to achieve meaningful conversation outcomes, and you can hear how conversations between a son and his Republican U.S. representative father converted the latter into a conservative climate champion.

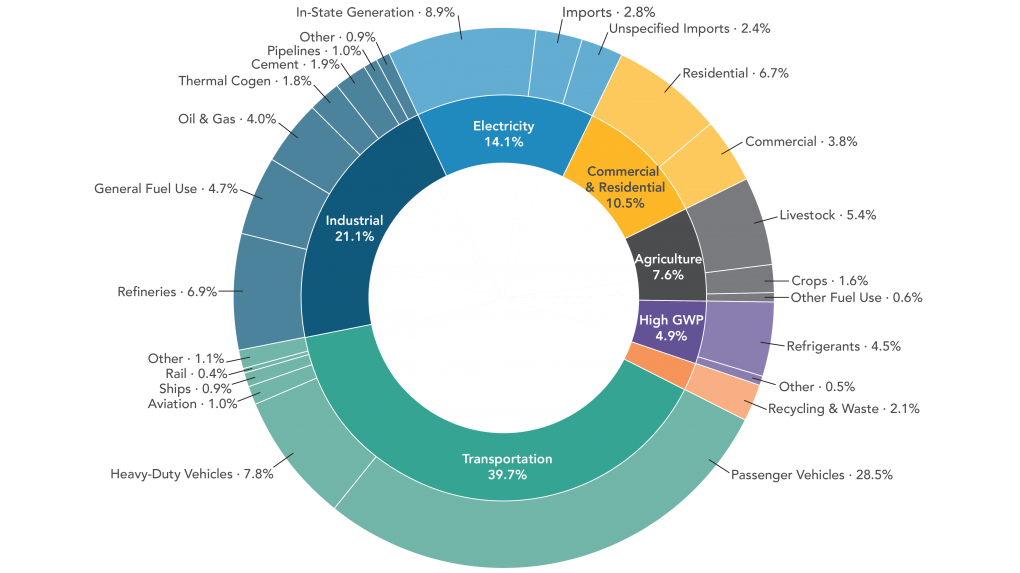

Drive less: The majority of California’s greenhouse gas emissions come from transportation, and for the average U.S. household, gasoline for personal cars is the the biggest source of emissions.

Most emissions come from long car trips.

Reducing travel in gas cars is one of the biggest things you can do, but can be challenging depending where you live. (This is one place where changing the system comes into play — working for better bus, train, biking and walking routes would make our cities and towns more friendly to ditching cars.)

Regardless, reductions in emissions from car trips help, whether that means having no car, taking public transit more, or switching to an electric or hybrid vehicle.

Plus, there are plenty of physical and mental benefits to other, familiar options like walking and biking.

Fly less: Only 1% of people cause half of the emissions from air travel. While carbon dioxide emissions from flights are roughly 2.4% of total greenhouse gas emissions globally, if you’re in that select group of people flying, and flying a lot, cutting down on flights will have an outsized impact on reducing carbon emissions.

Eliminate flights that aren’t essential, and if you’re a frequent flyer, set a goal to cut flights in half, or down to a few per year.

The shift away from air travel during the COVID-19 pandemic modeled what less flying can look like.

Eat a plant-based diet: Growing food for us and food to feed animals (that become food for us), plus deforestation (primarily to grow food) accounts for roughly 24% of global emissions. Methane comes from cow, sheep, and goat burps and their manure, and nitrous oxide from using fertilizers. Some carbon dioxide is also released from plowing and razing forests. Globally, deforestation is also the main driver of the biodiversity crisis.

Beef is more resource intensive than other foods. Producing it requires 22 times more land and emits 62 times more greenhouse gases per gram of protein than plant proteins like beans.

For meat eaters worldwide, cutting back to 1.5 burgers a week would nearly eliminate the need for agricultural expansion, even with a global population of 10 billion.

The average American eats three burgers a week.

Green your home: Energy we use in our homes is the second-biggest source of emissions for the average American. You can change that by installing solar panels and efficient windows, and improving insulation. And when some of the biggest home energy hogs need replacement, choose a more efficient alternative: swap your natural gas furnace and water heater for electric heat pumps, replace your gas stove with an induction one.

Many of these changes aren’t achievable as a renter, but you can bring this up with your property owner, and depending on where you are, there are programs that help with incentives.

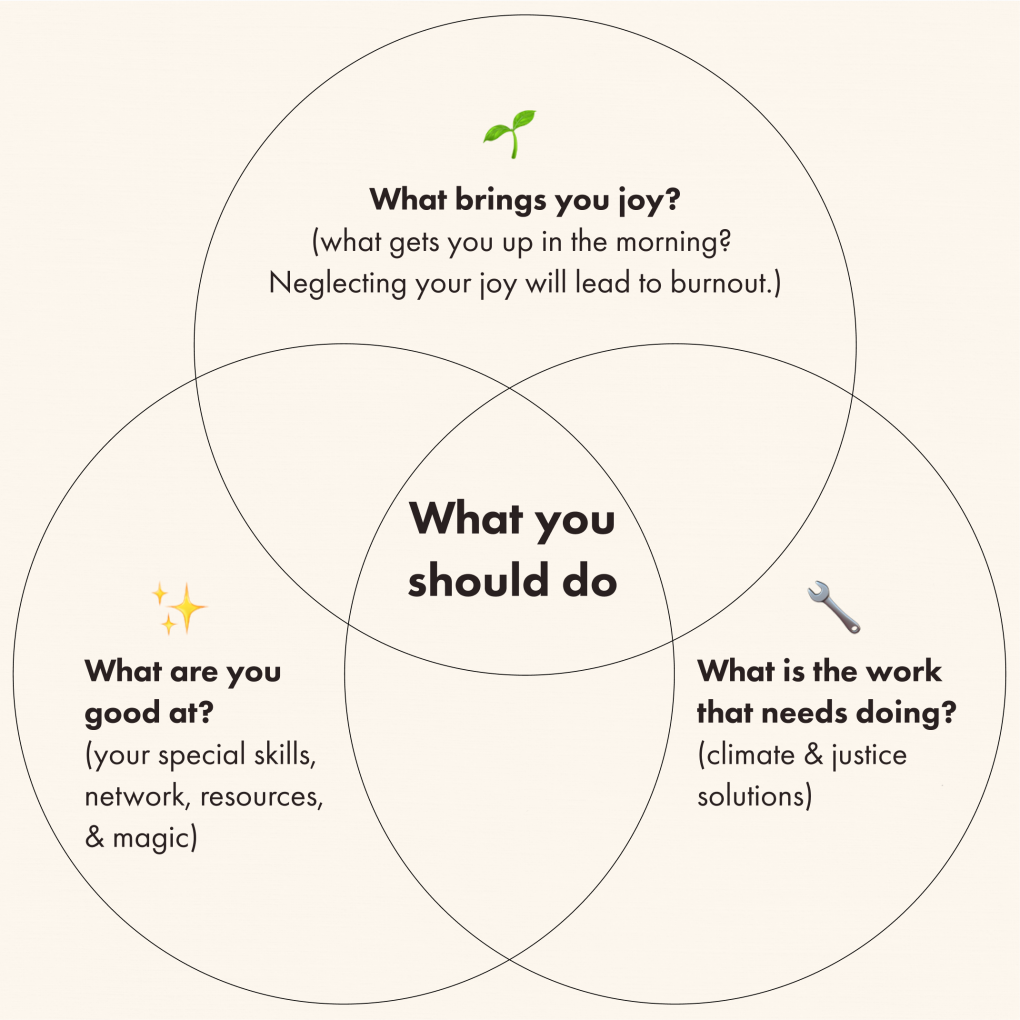

Your climate Venn diagram: In the podcast “How to Save a Planet,” host and marine biologist Ayana Elizabeth Johnson suggests one way to find your space in climate action: a Venn diagram.

Get out your paper.

What are you good at? “What skills, resources, networks, reach, influence are you bringing to the table?” she asked.

What work needs doing? The crisis is so huge that there are many options.

What brings you joy? “What gets you out of bed in the morning? Because this is the work of our lifetime,” Johnson said.

Your job is to move forward on what you identify at the center of those circles.

Active hope: Hope for the climate is not about crossing your fingers and going about your daily routine.

It’s a practice, say climate activist Joanna Macy and psychologist Dr. Chris Johnstone in their book “Active Hope.” This kind of hope involves taking stock of our painful reality, identifying what changes you want to see, and beginning to make them.

Doing these things brings us closer to others doing the same. The hope and action beget more of the same.

Yes, climate change is here. Yes, it’s bad.