When it comes to studying glacier ice for records of past climates, the poles are easy: Antarctica and Greenland have huge ice caps that we can drill cores in to our hearts' content. The real problem is in the rest of the world, where we all live. Scientists cannot model the global climate of the past with data from the poles alone. So a newly published ice-core record from the tropics is real news.

Tropical glaciers are few, scattered and endangered. South America and the Himalaya have most of them, and nearly all have been shrinking rapidly for several decades. Professor Lonnie Thompson of Ohio State University has specialized in drilling ice cores from them for more than 30 years, and the very first one he cored, in 1983, is a remote ice cap south of the equator in Peru named Quelccaya whose top sits above 18,000 feet. There he pioneered the use of a lightweight, solar-powered drill rig and succeeded in collecting two complete cores through the ice, about 160 meters long. Unable to keep them frozen, he had to cut them into sections and let them melt, then brought the water home in bottles.

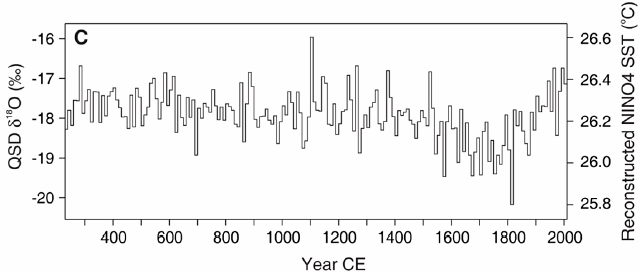

Twenty years later Thompson returned and brought two new cores, intact this time, to Ohio State's ice locker. In a paper published today in Science, Thompson's team shows that the 1983 and 2003 cores faithfully preserve a year-by-year record of tropical climate 18 centuries long, extending back to the year 683 with annual resolution and a little less perfectly back to almost 200. Thompson calls it "the longest and highest-resolution tropical ice core record to date."

The possibility of retrieving such precise records was what excited Thompson from the beginning. The ice consists of spectacular annual layers that represent dry winters and wet summers. The winter layers collect the lion's share of the year's dust and dissolved chemicals while the summer layers represent rainwater from the Atlantic Ocean, filtered through the tropical Amazon basin.

The data from the Quelccaya cores shed light on many scientific problems related to climate. Most notably, the extent of summer snow from the east depends strongly on Pacific Ocean influences from the west, such as El Niño cycles—so strongly that the Atlantic snow record shows us the temperature of the Pacific as if in a mirror. And Pacific sea-surface temperature is one of the most important numbers in the planetary climate because it's the best gauge of how much water vapor enters the atmosphere.

The climate record in the Quelccaya cores gives us the nearest thing to real truth in the centuries before modern science. It helps sharpen the picture provided by other ice cores, especially those in the tropics. And that in turn makes global climate records, and the models built upon them, more robust as we peer into the past and future.