Early in February of 2008, just days after she was born, Tatiana Legkiy lay in a cardiac intensive care unit, her tiny body hooked up to a respirator. After crying for two hours, she was now briefly quiet, the tube in her throat helping her breathe but also preventing her from making any sound.

Tatiana’s heart was failing. A cardiologist, tipped off by a pediatrician who heard something strange in a routine checkup, had examined her earlier that day and grown worried. He sent Tatiana to a nearby hospital in Modesto, California, where she remained for only an hour before being whisked eighty miles west by ambulance to the UCSF Benioff Children’s Hospital.

Tatiana’s parents arrived at the hospital shortly afterwards. At the time, Lana and Andrey Legkiy lived in Manteca, a city in California’s Central Valley. Andrey worked at an animal supply company; Lana stayed home and took care of their four-year-old daughter, Anna. Weekends found the the family outside together, camping or fishing in the Delta where the San Joaquin and Sacramento rivers flow into the ocean.

Even before Tatiana’s birth, the Legkiys knew medical hardship well. A year earlier Lana had suffered a miscarriage, losing an unborn child, a boy, in her third trimester. At the time, physicians had ascribed his cause of death to pulmonary hypoplasia, or incomplete development of the lungs.

Given that medical history, when Tatiana arrived at Benioff in critical condition, the doctors requested slides from the unborn child’s autopsy. This time, taking a closer look at small samples of heart tissue, they noted the true cause of death — an extremely rare heart condition known as left ventricular noncompaction (LVNC), in which the heart muscle remains immature and cannot pump blood normally.

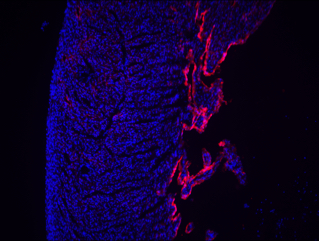

Visually, physicians identify LVNC by the fingerlike protrusions of muscle extending from the wall of the heart into the left ventricle, which supplies the body with oxygen-rich blood. An echocardiogram of Tatiana’s heart showed these same characteristics.

Gently, the physicians told Tatiana’s parents that there would be no surgery, but only because LVNC has no cure.

A Hunch

Immediately, Deepak Srivastava, then-attending physician at Benioff, suspected a genetic connection. He was a geneticist, after all, and Tatiana’s unborn sibling had shared the same disease.

Though he could not have foreseen it as Tatiana struggled for her life that day, proving this intuition would require over a decade of work. It would also require technology which was only just becoming usable, and the dedication of researchers he had not yet met.

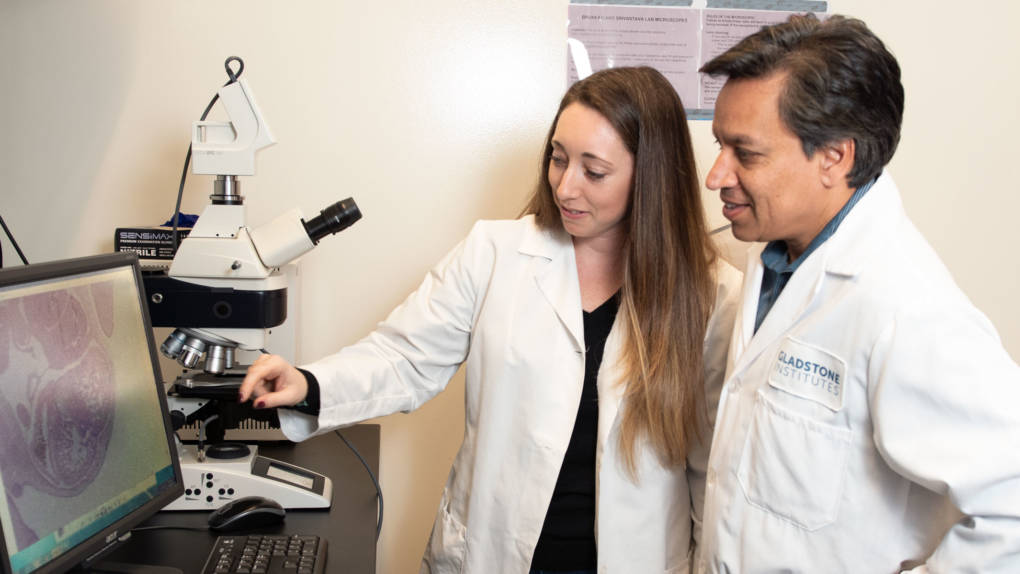

In the coming years, Srivastava would move forward with his own career, juggling the roles of biology professor, pediatric cardiologist, and ultimately president of Gladstone Institutes, a nonprofit biomedical research institution in San Francisco.

But the story of the Legkiys would stay with him. For a decade, he wouldn’t be able to shake the desire to pinpoint a precise genetic cause of LVNC, a necessary first step towards finding a cure for the disease. With that knowledge, physicians could rapidly screen potential drugs using an accurate, personalized model for patients like Tatiana.

Adding to the urgency of the Legkiys’ situation: Tatiana was not their only child. Even as Tatiana received her diagnosis in 2008, her happy four-year-old sister, Anna, ran around the hospital waiting room. Blissfully oblivious, Anna charmed the physicians, who began to wonder: did all three Legkiy children share the same disease?

As Tatiana stabilized, thanks to medication helping her heart pump and a respirator helping her breathe, Srivastava’s team set about finding an answer. Two days after diagnosing Tatiana, the scientists took an echocardiogram, a kind of ultrasound, of her father’s heart. They observed that Andrey had a less severe, asymptomatic case of Tatiana’s condition.