The three-person exhibition now filling SF Camerawork’s second-floor gallery space could easily be titled Other Americas, or even Policing of the Past, Present and Future. Instead, it’s Focal Points, the kind of photography-pun-as-exhibition-title that doesn’t tell you much about the extraordinary images in it, let alone the deeply researched narratives presented by photographers Sarah Blesener, Brian L. Frank and Tomas van Houtryve.

But that’s okay — a picture’s worth a thousand words, right? Focal Points gathers Blesener, Frank and van Houtryve as the inaugural recipients of the CatchLight Fellowship, which provides photographers with a $30,000 grant and a media partner (Blesener, for instance, was paired with the Center for Investigative Reporting) to help facilitate their proposed project.

While the three photographers’ subject matter seems at first glance to be wildly different (training camps for young patriots, a forest prison for incarcerated youth, and the pre-1848 border between the U.S. and Mexico, respectively), they all depict lives little-seen in mainstream media. They also all show how people have been historically disenfranchised, aggressively policed and trained to police.

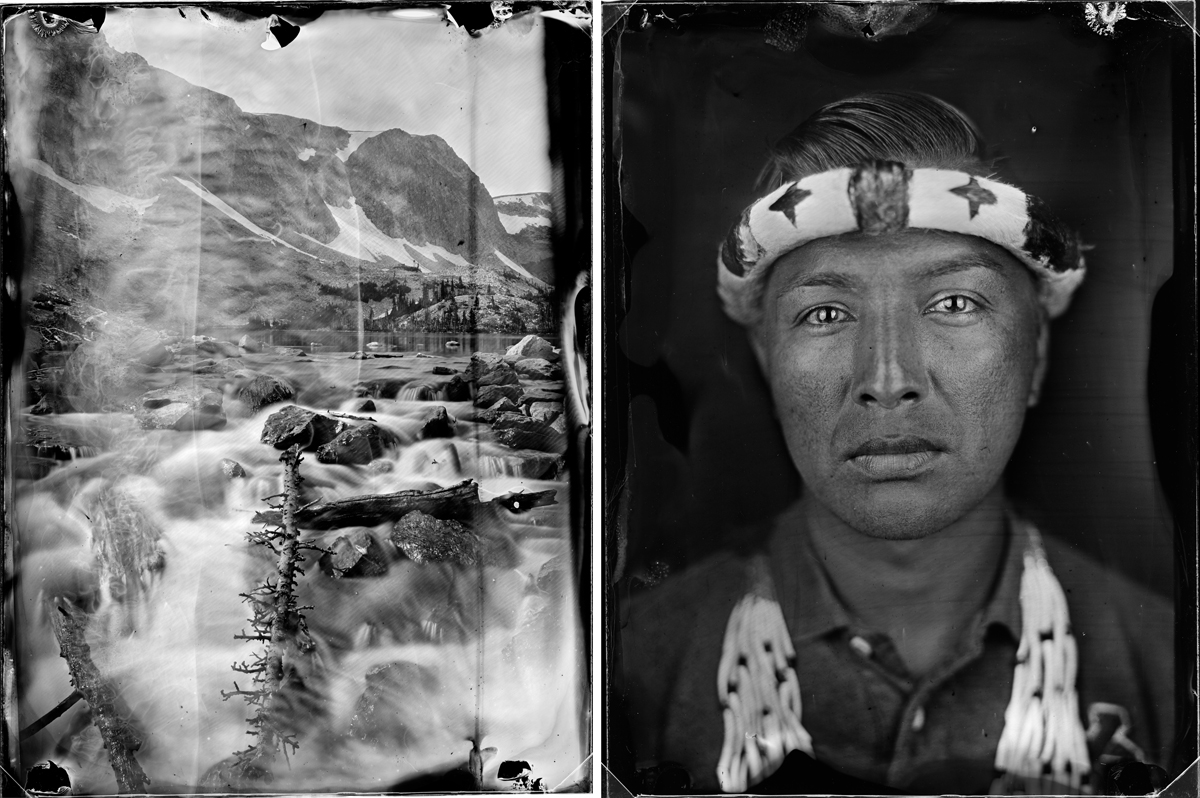

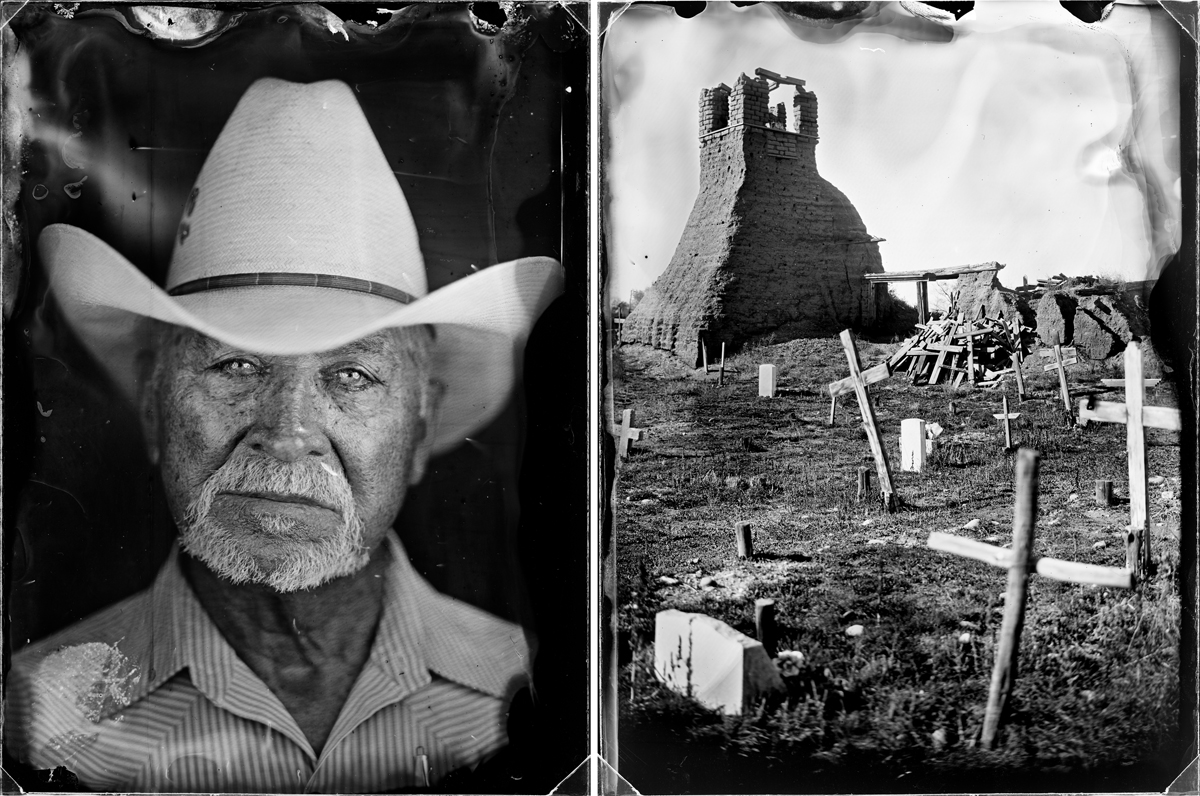

Van Houtryve’s Lines and Lineage is based on the Paris-based, San Francisco-born photographer’s long-term interest in what visual records can tell us about the world, and what’s missing from those records. His selection of images opens with a map of North America from 1839: Mexico stretches up the Pacific coast to the 42nd parallel (today the border between California and Oregon), across what we now call Nevada, Utah, Arizona, New Mexico, Texas, half of Colorado and bits of Wyoming, Kansas and Oklahoma.

That border, which existed from 1821 (Mexico’s independence from Spain) until 1848 (the end of the Mexican-American War), made up van Houtryve’s path as he photographed both the descendants of people who lived in this contested space before it became the United States, and the landscape itself. These photographs, made with glass plates and a 19th-century camera, are van Houtryve’s attempt to fill in the holes from that period’s visual history. The post-1848 American West — that’s well documented, he says, perpetuating myths of white “pioneer” life — but the same land under Mexican rule escaped visual record, simply because photographic technology didn’t arrive in time.