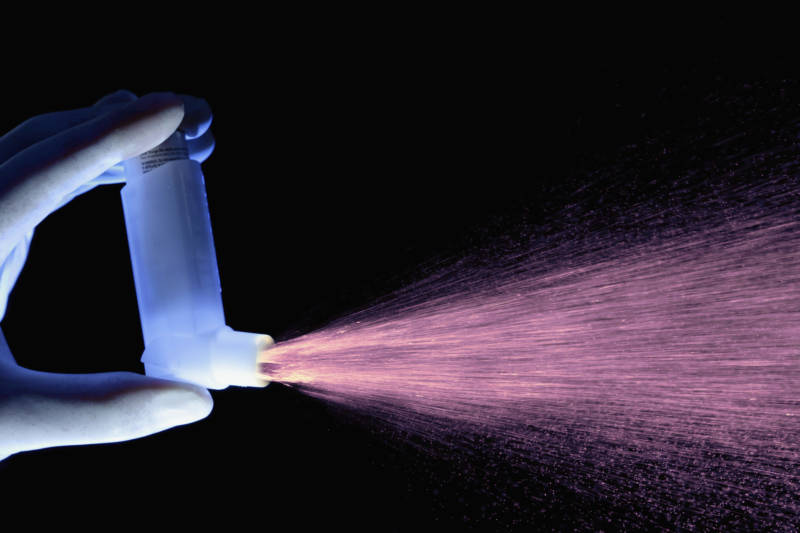

Steroid inhalers commonly used by asthma patients to prevent and reduce asthma attacks may not work any better than placebo, according to a new study published Sunday in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Gold Standard Asthma Treatment May Not Be Effective for Most Patients With Mild Asthma

Synthetic corticosteroids mimic the steroid hormone cortisol, reducing inflammation in the airways. But the drug targets a type of inflammation that may be found in far fewer patients than previously thought. Among those patients, more than half did just as well or better on placebo as they did on the steroid inhaler, the research found.

“We’re suggesting that it’s time to re-evaluate what the standard recommended form of treatment is for these milder patients,” said Dr. Stephen Lazarus, a pulmonologist at the University of California, San Francisco, and the study's lead author.

Since the early 1990s, international guidelines for treating patients with mild, persistent asthma has been to use a low-dose steroid inhaler twice a day. The recommendations were based mainly on studies of people with severe asthma, but the thinking was, if people with mild symptoms used the steroid inhaler early on, it would prevent damage to their airways later.

But when the medications didn’t seem to reduce asthma attacks, doctors blamed the patients.

“For many years, I think we’ve attributed their poor asthma control to the fact that they weren’t taking their medicines, and it may be that many of them were taking their medicines, they just weren’t working,” Lazarus said.

Lazarus and his team studied 300 patients with mild asthma. The vast majority, 73%, did not have type two inflammation — an inflammation characterized by a high level of eosinophilic white blood cells, which are believed to be much more prevalent among asthma patients.

Of those patients, 66% did just as well, or better, on placebo as the steroid inhaler, mometasone, in terms of urgent care visits, days when they had trouble breathing or woke up in the middle of the night unable to breathe.

Merck, the drug company that makes mometasone, declined to comment on the study.

“We may be giving people steroids, subjecting them to potential adverse effects and the increased costs without a significant clinical benefit,” Lazarus said.

While inhaled steroids are generally safe, there is some risk for bone loss, cataracts, glaucoma and thinning of the skin.

Bone loss has long been a concern for asthma patient Suzanne Leigh.

“I’m a low-BMI, white woman with a history of auto-immune disease, which puts me at high risk for osteoporosis,” she said.

Leigh works in UCSF’s media department and when she read the study, she was frustrated. She uses an asthma inhaler that costs $500 and puts her at risk of breaking a hip in a few years. And it may not even work?

“I don’t know where I go from here,” she said. “Do I continue with the medication or do I stop and end up in the emergency department?”

While the study certainly suggests the paradigm on treatments for mild asthma may shift, Dr. Lazarus said, a bigger, longer study is needed before any major clinical changes are made.

“If someone has evidence of episodic, periodic asthma and asthma exacerbations that lead to emergency department visits and they respond when treated with inhaled steroids, then it kind of doesn’t matter what the lab test shows,” he said. “If they have a clinical response that is genuine, that probably is an appropriate treatment regimen.”