We hear a train, then a siren. Fade. Another on-screen message: “This film is dedicated to all the brothers and sisters who had enough of the Man” (no period).

Back to the boy. No dialogue, but we hear the exaggerated clang of dishes. Now the boy is carrying towels; a woman beckons him to her room. She takes her clothes off, then undresses him. Some sort of industrial machinery on the soundtrack. She pulls the boy, maybe all of 12, on top of her. “Move!” she chides. A gospel song on the soundtrack. The boy dutifully humps the woman, who is brought to orgasm. “This little light of mine, I’m gonna let it shine!” we hear sung. “F—,” the woman moans. “You got a sweet, sweet back.”

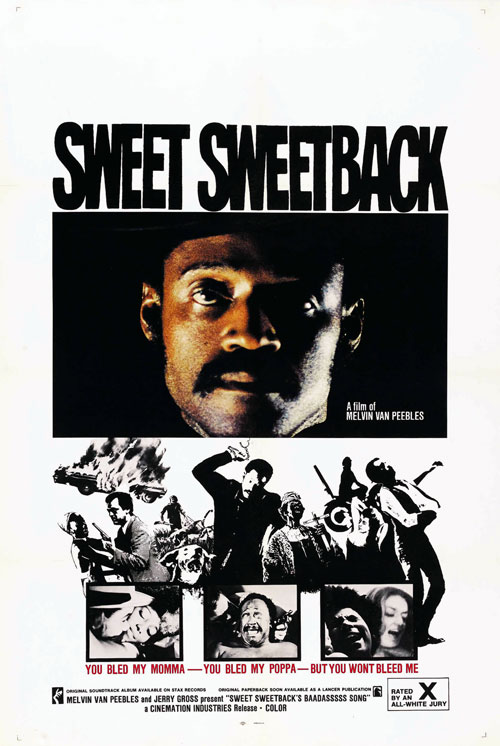

Freeze frame. Big red letters in cartoonish font cover the screen: “Sweet Sweetback’s Baad Asssss Song.” Jazz-funk music over credits:

Starring

THE BLACK COMMUNITY

and

BRER SOUL.

We’re five minutes in and, uh, just what the hell is going on here? Imagine the disorientation, before blaxploitation took hold, from all those black faces on-screen, alone. (Tyler Perry, Spike Lee, Denzel Washington, Wesley Snipes, Samuel Jackson were all just gleams in Hollywood’s eye.) The rest of the film is a political bomb thrown at the movie establishment, and at the “technological colonization of the white aesthetic,” as Van Peebles put it.

The boy who lays down with the prostitute (played by Van Peebles’ son Mario) in one freakishly effective cut arises a man. He now earns his keep as a sexual performer in a hard-core burlesque show for mixed-race audiences. Sweetback, as played by Van Peebles, does not derive even an iota of sexual satisfaction from the erotic encounters we see. When the show’s emcee, a fey black man in fairy godmother costume, invites audience members to have sex with Sweetback, a white woman is eager. But the brothel owner shakes his head — not in front of the white cops who have wandered in. “The offer’s only open to … sisters,” the emcee adds.

At the time of the film’s release, at least one black group was critical: “Van Peebles pictures sexual freakishness as an essential and unmistakable part of black reality and history, a total distortion and gross affront to black people.” But some black Americans undoubtedly related to the total lack of agency experienced by the character. Objectified, fetishized, Sweetback is such a complete cipher that his employer hands him over to the cops to serve as a fake suspect in a murder. While taking Sweetback to the station, the policemen arrest a young black radical and work him over. For a time Sweetback impassively observes the brutality. But he eventually comes to the radical’s defense, attacking the cops. From then on he roams L.A. as a fugitive. We frequently see him literally on the run, and not necessarily from an immediate pursuer, so that his flight becomes the central metaphor of the film, an almost mythological task. Between these desperate flights, the rest of the film happens: Sweetback has various encounters as the police continue their search, and he winds up in the desert with LAPD canines hot on his trail.

Van Peebles recounted a story from the movie’s opening in Atlanta, sitting next to an elderly black woman who mumbled, “Oh Lord, let him die in the desert, don’t let them kill him.” He said about the incident: “It was beyond any thought that someone would defy a white authority and live.”

Which brings up the film’s most explosive component: the overt racism and brutality against blacks on display by the LAPD, an issue that has plagued the department and the community it polices for decades. We see white police fire a gun next to a black man’s ear; the police commissioner spits out a “nigger” then apologizes to his black officers: “I didn’t mean any offense by that word.” In a case of mistaken identity, cops brutally beat a black man in bed with a white woman. “That’s not him,” one of them realizes. “So what?” says the other.

Not exactly crossover material. While Sweetback is often credited with ushering in the blaxploitation genre, it has a much rawer quality than those subsequent 1970s films. And as far as style goes, well, call it impressionistic, call it off-the-wall, or call it a travesty, even. I’ve seen it four times and I still have a hard time figuring out what’s going on. Some audiences weaned on traditional film grammar will find it utterly inaccessible, and you can’t always determine what is a piece of experimental brilliance and what is simply a mistake. If the film has any stylistic antecedents, they’re the films of the French New Wave.

Though he’d directed two other features, Van Peebles began his career with no training. He made Sweetback with a non-union, multi-ethnic crew, half of whom had never seen a camera before, according to the director. They shot guerilla-style, working 20-hour days for almost three weeks. Things went helter skelter on the set. Crew members were arrested. A real gun wound up in the prop box. The film uses mostly amateur actors (including Van Peebles as Sweetback, his stoicism logical and effective, but just as likely due to lack of ability), and the dialogue often feels improvised or uneasily remembered. Dubbed lines, color filters, cross-cut sequences disjointed by an inconsistent soundtrack, repeated shots, freeze frames, double exposures, barely visible lighting — all on display.

Even the music at times disintegrates into a shambles. But it’s also the music that frequently compels us to keep watching, and the film actually might be intolerable without it. Written by Van Peebles and recorded by newcomers Earth, Wind and Fire, the jazz-funk score is an all-time great. While you can often lose the narrative thread of Sweetback, the music married to frequently striking visuals provides some sublimely lyrical moments, a poetic soul-on-fire feeling evoking the metamorphosis of degradation into resilience. It’s probably as apt an anthem as any for the roiling rebellion of that era.

Contrary to the Atlanta woman’s fatalism regarding cinematic rebellion by black people, Sweetback manages to escape his pursuers, and the film ends with another on-screen message: “Watch out… a Bad Assss nigger is coming back to collect some dues.”

We never did get to see that payment — Van Peebles did not make the sequels he’d intended. So those who craved cinematic catharsis in the form of black retribution against the white power structure had to wait until a white director offered it up 40 years later.

Before Sweetback, Van Peebles had once looked forward to completing a three-picture deal with Columbia, but he’d quarreled with the studio over the ending to Watermelon Man, a film about a bigoted white man who one day wakes up black. Van Peebles said he sunk “every penny I had” into Sweetback, completing it with no studio money and a production-saving $50,000 loan from — of all people — Bill Cosby. His studio career over, he turned to the theater, music, and other endeavors.

Not every critic took to Sweetback, as you may imagine. Vincent Canby of the New York Times reviewed it like this:

“The movie is the story of Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Flight, accompanied by lots of soundtrack song, a journey made eventually intolerable not only by the hardships and the duplicity (of even white counter-culturalists like the Hells Angels), but by the simplistic sensationalism of the treatment and the eye-disorienting visual style that substitutes film school technical complexities (such as the superimposition of double, triple and quadruple images) for dramatic content. Instead of dramatizing injustice, Van Peebles merchandizes it. With the exception of perhaps a dozen scenes, the movie is composed almost entirely of the sort of fancy montages with which television (is) the goal. Still to be found are a director and a choreographer to guide a cast of about 25.

But I think of this in-your-face look at institutional racism along the lines of Henry Miller’s definition of his own Tropic of Cancer: “This is not a book. This is libel, slander, defamation of character. This is not a book, in the ordinary sense of the word. No, this is a prolonged insult, a gob of spit in the face of Art, a kick in the pants to God, Man, Destiny, Time, Love, Beauty …” Indeed, some things in this movie only John Waters could love: a man on a toilet moving his bowels and wiping himself, a man biting into a raw lizard, a dead dog drowned under water. It all adds up to the sense of being privvy to a perversity usually kept under wraps, and one uniquely disconnected from the American Dream.

And, it must be noted, black audiences ate it up. As told by Van Peebles, he could only open the film in two theaters, one in Atlanta and one in Detroit. In Detroit, only three people came to the first show and none to the second. But for the third, the Black Panthers showed up in force and eventually the lines went around the block as word spread. The film did by some accounts $15 million at the box office on a budget of $500,000, partly because of heavy promotion by the Panthers.