In the latest round of Star Trek movies, San Francisco finally became a city of the future; at least on the screen. The movie and the city both looked great, even though one might be given to wonder if any elected Board of Supervisors would OK a spaceport in the midst of the downtown skyscrapers.

But San Francisco and the Bay Area have a rich literary history in the future. You can leave your everyday girl-power dystopia at the box office, and saunter in the quite lovely present to any of a number of independent bookstores to find a variety of volumes that present “Baghdad by the Bay” in an imagined future. Happily, dystopias and apocalypses sometimes prove to be a good thing. San Francisco’s unique landscape and cityscape are fertile ground for the writers’ imaginations.

It’s important to remember, as you choose your future, that any given book, no matter how imaginatively conceived, is written in the present. Even the most wildly crafted vision takes its cues from the times in which it was written. In this selection you’ll find visions of the future set in the past, and visions of the future informed by the present. Science fiction is notoriously bad at predicting future, but it’s often spot-on when it comes to describing how it feels to be living in a present that is moving faster than we’d prefer.

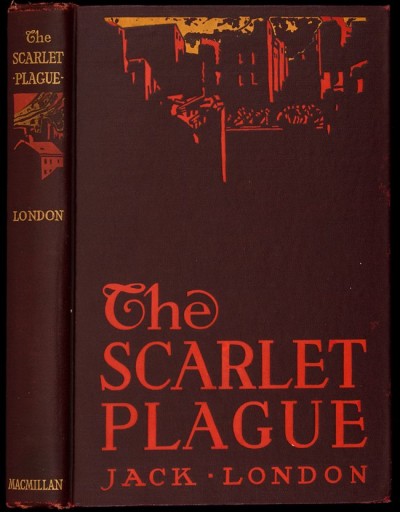

Jack London, The Scarlet Plague (1915)

Jack London, best known for Call of the Wild, was also on the cutting edge of science fiction 100 years ago. First published in 1915, The Scarlet Plague unfolds in the year 2073, sixty years after The Red Death has wiped out most of mankind. The plague first takes hold in the summer of 2013, so readers can be assured we’re not too far into this particular apocalypse. The novel is an excellent early version of the “last men on earth” genre that’s overrunning today’s bookstores. James Howard Smith, one of these last men, takes his time to try to leave something of what he’s learned for those few(er) who will follow. For all his love of the wild, London did not see in depopulation the potential for an Edenic return to nature. Instead, he saw man as devolving into a barbaric state. An ardent anti-Capitalist, London authored another dystopia, The Iron Heel, which saw America under the thrall of an oppressive oligarchy just about now. He’d feel right at home in today’s San Francisco, churning out best-selling action blockbusters and able to afford a $3,500 first edition of his own book.

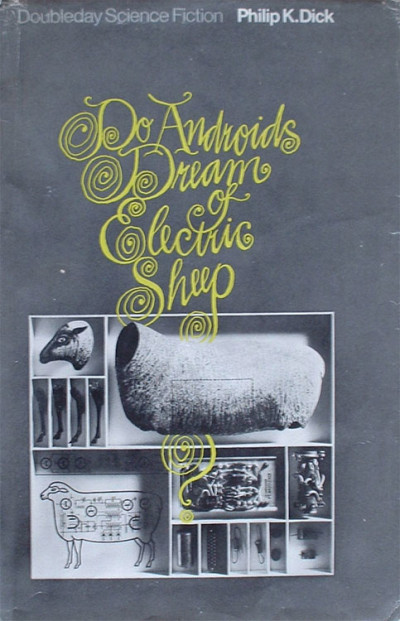

Philip K. Dick, Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? (1968)

Philip K. Dick’s most famous novel, the basis for the movie Blade Runner, is set, unlike the movie, in and around San Francisco. For Dick, the future was 1992 and after World War Terminus, the humans remaining on earth are slowly dying of radiation poisoning. Happily for the City, San Francisco is one of the least affected places. Rick Deckard is tasked with finding renegade Nexus-6 Androids, created for slavery on Mars, who have escaped to Earth and are trying to pass for human. As Deckard pursues his prey, he finds humans who seem artificial and androids who seem human. The power of empathy, for animals and humans, runs through the novel, as Deckard takes his flying car to the source, and administers tests to differentiate the real from the created. Dick’s novel is considerably more complex than Ridley Scott’s movie. Even if it is set more than twenty years in the past, Dick’s future feels tense and pertinent. For a novel that is not just dated, but twice dated, Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? has the timeless feel of fable.

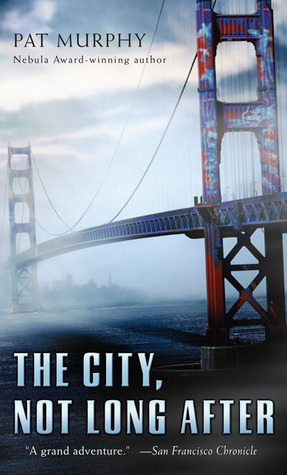

Pat Murphy, The City, Not Long After (1988)

Welcome to post-plague San Francisco, and The City, Not Long After, which, in spite of its premise, is a decidedly Utopian vision of artists and creators living in harmony 20 years after the end. Murphy’s novel perfectly captures the sense of San Francisco, with unusual, intense characters and the feeling of a future that plays like the present and is literally haunted by the past. The characters are a delight, sweet and weird. The Machine makes robots and believes himself to be one; Lily collects skulls with which to dress department store windows, and Danny Boy wants nothing less than to paint the Golden Gate Bridge blue. This is arguably the perfect post-apocalypse for San Francisco, a city overrun by artists who refuse to fight even when threatened by a military force bent on conquest. Moreover, and importantly, Murphy acknowledges the power that the past holds here, as the ghosts of San Francisco play an important role. Reverberating with themes of security versus liberty, the power of art and the peril of that power, Pat Murphy’s The City, Not Long After understands the present as well as it presents the future.

Richard Paul Russo, Carlucci: Destroying Angel, Carlucci’s Edge, Carlucci’s

Heart (1992-1997)

If you’re terrified of the Tenderloin, or love it as much as life itself, you’ll find a friend in Richard Paul Russo’s Carlucci, which collects three science-fiction noir novels set in the mid-twenty first century, as imagined in the late twentieth century. Intricate, intense and as over-the-top as anything you’ll find in San Francisco in real life, Russo’s cyberpunk crime novels are the apotheosis of how the science fiction genre uses a literary toolkit to paint a town that’s already red ten different shades of 3-D purple. The first novel finds Carlucci in more of a supporting role, but the follow-ons build a rich character arc and manage the neat trick of being page-turning pulp with a beating, bleeding heart. Find the paperback original in a used bookstore and revel in the gloriously cheesy covers, then pick up the trade paperback gives you all three for a song, in an eminently readable format. Russo is a highly underrated writer whose future is being revealed as each day peels away the rotting velvet veneer to show us the robotic skeleton we wish we could not see. These books are fun, dark and true.

Richard Morgan, Altered Carbon (2002)

The San Francisco of the 26th Century, portrayed in Richard Morgan’s Altered Carbon offers much of what the city does today: unthinkable wealth jostling up against unacceptable poverty. In Morgan’s universe, humans are stored digitally with “altered carbon” being the storage medium. As long as the Cortical Stack is not destroyed, humans can simply be refitted into another ‘sleeve’, also known as a human body. Having been killed off planet in the novel’s first scene, Kovacs awakens on Earth (‘the most ancient of civilized worlds’), in San Francisco, re-sleeved and the recipient of an offer he cannot refuse. One of Earth’s oldest and richest men, a true Methuselah (a ‘meth’) has committed suicide. Of course he’s immediately resurrected, but his backup was made two days before the suicide. The resurrected Laurens J. Bancroft doesn’t believe for a minute that his predecessor committed suicide. The police, in the form of the Organic Damage Squad’s beautiful Lieutenant Ortega, aren’t that interested in the case. Takeshi has to find the truth. Prepare for an intense and exciting novel where great characters and thought-provoking ideas are enmeshed in a smart, inventive mystery. (Morgan also took Kovacs off-planet in two sequels, Broken Angels and Woken Furies.)

Leigh Richards, (Laurie R. King) Califia’s Daughters (2004)

Men are an endangered species in Laurie R. King’s Califia’s Daughters. King, who wrote “Daughters” under the pen name Leigh Richards, knows genre fiction well and is a wonderful writer. In this novel, King’s inversion of reality as we know it proves to be a rather excellent portrait of the world as it is. After the plague, which was probably a primary color, Northern California is a land of warring tribes made up of mostly women. Men are kept and precious. When strangers come to Dian’s tribe, she’s off on a quest to understand their story, and, of course her own. King’s feminist vision manages to be rich and character-driven and well ahead of its time. Califia’s Daughters was in fact King’s first novel, and there’s clearly room for a much-desired sequel.

Dale Pendell, The Great Bay: Chronicles of the Collapse (2010)

Plagues are popular. It’s an easy way to wipe the slate clean. Unlike Jack London, who headed up this list, Dale Pendell finds the aftermath of his plague in The Great Bay, to be decidedly naturalistic and Edenic. It might take sixteen thousand years to get there, but it will happen. Of course, that’s only after rising sea levels transform what we now call the Central Valley into, well, The Great Bay. Pendell uses oral history to take readers through thousands of years, leaving us (that is the so-called present) behind in what he terms the Thermocene. Maps, journals, diary entries, newspaper clippings and field notes stitch together the story of humanity without technology. This generally proves to be a plus, so long as you don’t like technology too much. Pendell is a crafty writer with a grand, grand vision of the future. If H. G. Wells had the climate data, he might have attempted a book like this.