The Gaza war is a tragedy, a pointless and destructive clash whose only lasting effect will be to increase the suffering of civilians. That’s my perspective; you have yours. This isn’t a political blog, clearly, but I have to acknowledge what’s happening in the real world before I can talk about filmic representations of reality and our responses to those representations. Now imagine the meetings in the last week among the programmers of the San Francisco Jewish Film Festival.

The SFJFF, opening tonight and continuing through August 10 in San Francisco, Palo Alto, Berkeley, Oakland and San Rafael, is the first, largest and most liberal Jewish film festival in the country. Although it’s not as willfully provocative as it was in its radical youth, SFJFF consistently maintains the progressive values of compassion and justice that the Bay Area has long embodied. One way that shows up onscreen is the perennial inclusion of movies that acknowledge Palestinians are human beings with rights. That’s a radical attitude to some people — a provocation — and the SFJFF has taken a good deal of heat for it over the years. Even in “peaceful” years.

I would think the SFJFF brain trust would prefer that the festival not take place in the middle of a war, a crisis that compels bystanders to take sides and to question the loyalty of anyone who remains in the rational, reasonable middle (or expresses empathy for the losses endured on the other side). On the other hand, this festival has always held itself up as a place of discussion and debate, where views beyond the American Israel Public Affairs Committee mission statement get a hearing. (That’s one reason the festival has attracted a following among Jews who aren’t connected to synagogues and other Jewish institutions. I almost said “traditional” Jewish institutions, but after 34 years the SFJFF has achieved the status of an institution.)

The upshot is that the war will impel audiences to engage with the films on a more visceral and more meaningful level, and the festival brass will welcome (or at least accommodate) the rise in temperature. The stakes are higher, if you will; real life trumps academic and hypothetical arguments. That’s human nature. But let’s not forget that the “normal” state of affairs between Israel and the Palestinians is anything but placid.

So, can we talk about movies now? You can see more about the films or buy tickets by clicking on the film titles.

Truth Is Stranger Than Fiction

In the opening night slot, where festivals typically seek out un-challenging, crowd-pleasing narratives to set an innocuous tone, SFJFF programmed Nadav Schirman’s nonfiction nail-biter, The Green Prince. Based on the memoir Son of Hamas, the documentary recreates the clandestine dealings between the son of a Hamas leader and the Israeli intelligence agent who he funneled information to about imminent suicide bombings and other attacks. The relationship between the two men came to transcend their respective loyalties, and this feel-good aspect, presumably, persuaded programmers to make it the curtain raiser. Alas, peaceful coexistence is a remote concept at the moment.

Date Film

Israeli filmmaker Talya Lavie developed her acerbic and piercing debut, Zero Motivation, at the Sundance Lab, and it boasts a stronger structure and more coherent vision than most indies. With a sharp intelligence, the film depicts the escapades and rivalries of the low-level female desk jockeys at a nowheresville military base. Lavie zings darts at sacred cows and underdogs alike, pitching her movie somewhere between a smart chick flick and a satire of military intelligence.

Your Conscience Is Calling

The most important film in the entire lineup, hands down, is Watchers of the Sky, Edet Belzberg’s meditative documentary about the “inventor” of genocide (Viennese Jew Raphael Lemkin, who developed the concept, invented the word and lobbied and labored the UN for years to codify its legal ramifications) and his contemporary successors in the thankless field of bringing mass murderers to justice.

Fathers and Sons

Israeli directors Guy Nattiv and Erez Tadmor combine a couple of every filmmaker’s favorite subjects, estranged families and road trips, in the enjoyable, picturesque and occasionally moving Magic Men. A widowed baker returns to his Greek birthplace after many years, accompanied against his will by his despised Hasidic son. This soulful film largely evades the potholes of clichés, including the hooker with a heart of gold (and a young son).

Sex On Camera

Joseph W. Sarno wrote and directed dozens of arty soft-core movies in the 1960s and ‘70s before hardcore and home video killed off the grindhouses. Peggy Steffans horrified her upper-middle-class Jewish parents by acting in a few of those films and marrying the director. Swedish filmmaker Wiktor Ericsson’s A Life In Dirty Movies profiles an uncommonly candid couple, and fills in a fascinating chapter in film history. David Cairns and Paul Duane do the same for Bernard Natan, a Romanian Jew who became a leading producer of French silent films and turned Pathé into a major studio in the 1930s before the bottom fell out. Natan introduces and rehabilitates a profoundly tragic figure, whose reputation continues to be sullied by the charge that he performed in pornographic films in the ‘20s. (Natan actually contains more explicit images than A Life in Dirty Movies.)

Everyone’s a Critic

El Critico, another title of special interest to film lovers yet accessible to all, follows a divorced, morose Argentine film critic through his dreary existence, which consists mostly of watching and eviscerating insipid mainstream Hollywood movies. First-time director Hernán Guerschuny has fun mocking the conventions of romantic comedies before employing them to portray the critic’s own out-of-the-blue love affair. Perfectly passable entertainment, even if it flags in the middle and only contains one fleeting bit of Jewish relevance.

Justice League

East Bay filmmaker Abby Ginzberg, an attorney turned documentary maker, delivers her most accomplished work to date with Soft Vengeance: Albie Sachs and the New South Africa. This deeply inspiring film profiles the principled, primary legal mind of the African National Congress, who eventually became one of the original justices of the Constitutional Court created after apartheid. If you think lawyers aren’t compelling enough to carry a movie, consider that he was targeted for assassination by car bomb (he lost an arm) by the South African government while in exile in neighboring Mozambique. Sachs’ response at the time couldn’t be more applicable to the Israeli-Palestinian situation: “An eye for an eye, and an arm for an arm. Is that what freedom means? The idea fills me with anguish.”

Suitable for Children, and Everyone Else

As his bar mitzvah approached, San Franciscan Mica Jarmel-Schneider decided to collect and send baseball equipment to Cuba as a social-justice project. Havana Curveball (a world premiere) follows his ever-expanding campaign, which ultimately led to the island to guarantee delivery of the gear. Mica’s savvy filmmaker parents, Marcia Jarmel and Ken Schneider, go beyond simplistic platitudes to convey the disappointments that can accompany doing the right thing.

You Say Schlemiel, I Say Shlemazel

Even if you know nothing about Yiddish culture, here are words to live by: Anything with Molly Picon is worth seeing. Mamele, Joseph Green’s marvelous comic melodrama finds the vastly talented actress taking care of her underemployed, unappreciative siblings and father. Made in Poland in 1938, when life was terrible for Jews and about to get unimaginably worse, Mamele screens in a new restoration.

A Little Night Music

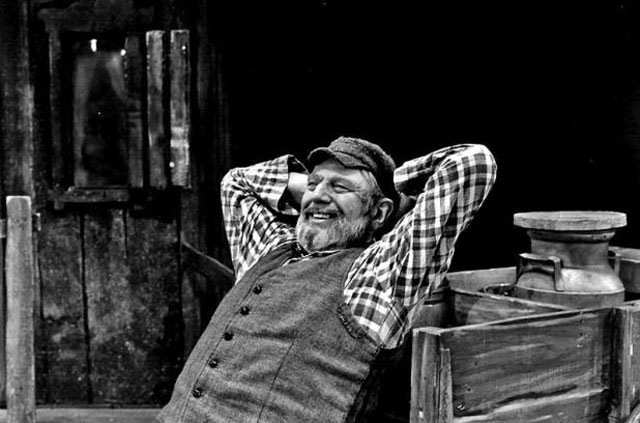

The singer and actor Theodore Bikel, who played Tevye in hundreds of performances of Fiddler on the Roof, comes to town to receive the SFJFF’s annual Freedom of Expression Award. The 90-year-old legend is going to sing a tune and perhaps recite a poem or text, showcasing the gifts on display in Theodore Bikel: In the Footsteps of Sholem Aleichem. John Lollos’ performance-packed doc, receiving its world premiere at the festival, is destined to have a long life — as long or longer than Bikel’s, God willing.

Politically Incorrect

Somehow I’ve managed to get this far without mentioning the films that are likely to provoke the most complicated responses from audiences. Local filmmakers Judith Montell and Emmy Scharlatt’s In the Image: Palestinian Women Capture the Occupation (receiving its world premiere) shows us the occupied West Bank and the indefensible behavior of settlers and soldiers. Our guides are ordinary women, whom we may have assumed in a patriarchal society only take care of the household and the children. Provided with camcorders and training by an Israeli human-rights organization, they discover their power, and the cost. Infuriating and tough to watch at times, In the Image represents the strongest indictment of the occupation in the festival.