MBJ: So you gotta understand, man, A Tribe Called Quest—first of all, they were from Queens. They referenced Linden Boulevard, and 192, and that’s up the street from where I lived. So that was a big deal.

And Tribe Called Quest, De La Soul, Jungle Brothers, the whole Native Tongues: those people made it okay for me to be black and weird. There’s the fashion that they introduced, the black bohemian sound and outlook, but the music that Tribe was sampling—and “Electric Relaxation” features this amazing Ronnie Foster sample, from “Mystic Brew”—totally opened me up musically, and also socially, to different expressions of the black experience beyond the boom-bap of, say, KRS-One, or the straight-ahead DJ / MC combo of Eric B. and Rakim or Gangstarr. This was a different sound. As a dancer who hadn’t yet embraced fully my poetic ambition and latent skill, I fell in love with the music first. I just couldn’t believe what I was hearing.

And I say all that, and then, I loved this girl. My prom date. And “Electric Relaxation” was a smooth-ass love song. I love that. And Phife’s line, “I like ’em brown, yellow, Puerto Rican or Haitian”—this was just a little bit after the Fugees, but even the Fugees weren’t putting their Haitian heritage upfront in such a memorable way, and in such a memorable song.

“Sound of the Police,” KRS-One

MBJ: The ubiquity of police presence in urban neighborhoods, and the looking-over-the-shoulder-ness of being a 17 year old African-American male in the summer of 1993, you know – growing up in New York, this is what I grew up on. From Michael Stewart to Yusef Hawkins, every year, there was some engagement with the police. And it hasn’t changed, right? The relationship between young African American males and our justice system has always been fragile and aggressive. And KRS has an exceptional talent for distilling macro topics into easily recitable histories.

That whole thing, “Overseer, overseer, overseer, overseer, overseer, officer, officer, officer, officer, officer”—it’s like, “oh, right!” Like, he literally took 150 years of a paramilitary presence in the life of African-American males and just distilled it into two bars, you know, “Check the similarity!” So it became, ironically enough, a type of badge, a weapon, in and of itself just to be equipped with historical allegory for the relationship between an African male as property and also as an agent of both change and disruption in the dominant hegemony.

And with all that being said, it just knocks so hard. Like, the low end on that song is stupid. And I remember being in places—and certainly this was true in Atlanta—where anytime somebody was in trouble, or when police was around, you could just go “Whoop! Whoop!” and folks knew exactly what you were doing. So it became a signifier, and still is a major signifier, within the culture. It just says so much. An onomatopoeia that does everything.

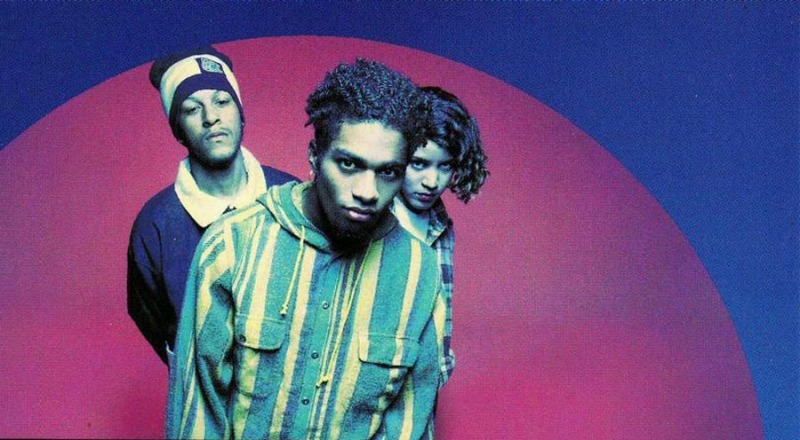

“’93 ‘Til Infinity,” Souls of Mischief

MBJ: As someone who graduated high school that year, it’s the anthem for 37-, 38-, 39-year olds everywhere. You know, youth culture is not about immortalization. As a young person, you feel immortal. You don’t need to be historicized. You assume that you’ll be 17 forever, and like, twenty-something feels really, really old. So there’s something in the complication of feeling immortal and timeless, and still being tethered to a particular year. “93 ’til Infinity”—that’s all the romance and bravado of what it meant to be a teenager in that year.

You know, I had no plans on living in California. I didn’t know what I was gonna do with my life, really, at 17. I wasn’t connected to Oakland in any way. I didn’t know that I would be married, and have kids, and have a mortgage here and shit, and dogs. I didn’t think I was gonna have this version of my life. But whenever I hear that song, I feel 17 again. I think it’s one of the many reasons why we love music: because it locates us in a particular time and place.

“Rebirth of Slick (Cool Like Dat),” Digable Planets

MBJ: You know, I still don’t know what those cats are saying! It’s funny, because the weakest rapper in the group, Doodlebug, he’s the one whose lyrics you know, because they’re so uncomplicated and straightforward. But the complexity of Mecca and Butterfly was really my introduction to spoken word. The jazz phrasing and the lack of commitment to a linear structure for storytelling—you know, De La Soul was in this family too, just in terms of the very tightly wound and intricately interconnected metaphors all wrapped around each other. De La Soul has that, but there’s a way that Digable, and on that song in particular, was almost arhythmical. Like, not anti-rhythmical, but that structure of the delivery wasn’t about one bar to another.

When I think about my current writing style, I was turned on by Ntozake Shange, by Nikki Giovanni, by Sonia Sanchez, and in a more prosaic way by Toni Morrison and Paule Marshall, but when I think about my writing style, the MCs that I owe the most debt to, in terms of a personal origin story, are Mecca and Butterfly. So I choose that song because it was probably the most influential, in that year, of how I currently like to write. That MCing sounds like the Harlem renaissance to me. “We be to rap what key be to lock”—that sounds like a Countee Cullen poem. It’s very simple, and intricate, right?

There’s so much to parse out in every individual line, but the meaning isn’t revealed to you at the end of the phrase. Which I think is how we hear most rap, especially in this modern era, this battle era, that’s so about the punchline at the end of the phrase. So it was the mystery of the song, and the relationship between the poetry that I was really into at the time—the poets of the Harlem renaissance—and the jazz era, with a hip-hop consciousness and flow. So that song didn’t turn me on to rap; that song turned me on to poetry. It told me I could be a poet, that was of hip-hop, who didn’t rap.

“I Am, I Be,” De La Soul

MBJ: This is like pure nostalgia for me. “I am Posdnous, I be the new generation of slaves / Here to make papes to buy a record exec rakes / The pile of revenue I create / But I guess I don’t get a cut ’cause my rent’s a month late.” It’s like, so vulnerable. You know, MCing is about so much bravado and armature, and when everybody else is talking about how much money they had—and this is before the bling era of rap, so everybody knew that nobody was makin’ money, but everybody was frontin’, like somethin’—and he talks about his parents! His mom, who didn’t get to see him “grab the Plug two fame / Now it goes a little somethin’ like this / Look ma, no protection, now I got a daughter”—it’s like, really? Okay. It’s like, his parents, unprotected sex, he’s a father, he’s not makin’ no money, you know what I mean?

Along with that, everybody else—the Bomb Squad, etc.—were working with Clyde Stubblefield, looking to the percussion on the James Brown side of things, and this was a group that was pointing to the J.B. Horns. But not in a funk way, but in a really sorrowful, pensive, contemplative, beautiful, lyrical way. The arrangement is bass, piano, horns, it’s a really beautifully composed song.