There is something antediluvian about world’s fairs. They still exist — one will open in Milan this May — but the concept sometimes feels from another time. The last world’s fair in the United States was held over 30 years ago in New Orleans, and was considered a failure; the more successful fair in Knoxville two years earlier reported a princely profit of $57. Though international events like the Olympics and the Venice Biennale share some similarities with world’s fairs, they still seem more appropriate to the times of Baudelaire and Zola, or at least Asimov and Disney.

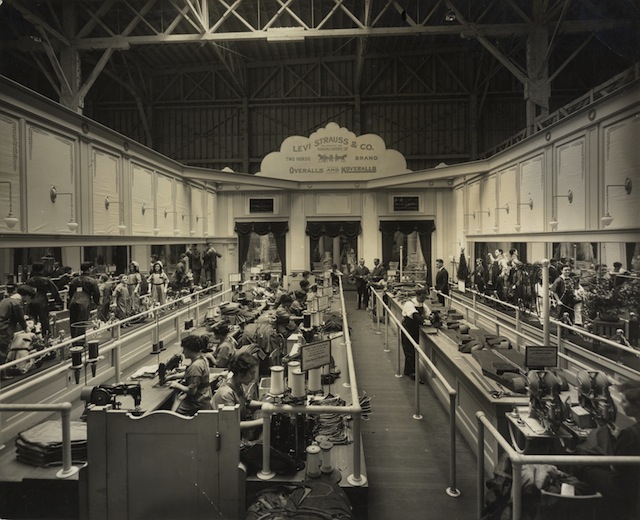

On the 100th anniversary of the opening of the Panama-Pacific International Exposition (PPIE) in San Francisco, I visited City Rising: San Francisco and the 1915 World’s Fair at the California Historical Society to search for an answer to why world’s fairs feel so antiquated today. City Rising explores the exposition from its emergence out the rubble of the 1906 earthquake to its demolition in 1916, making use of ephemera, posters, photographs, and even a large-scale reproduction of the fair grounds.

I brought with myself to the exhibition assumptions of national image-building and a narrative about the heroism of industrialism and imperialism. These assumptions were certainly substantiated, but City Rising helps make sense of the tenuousness of this narrative and how it relates to the contemporary condition.

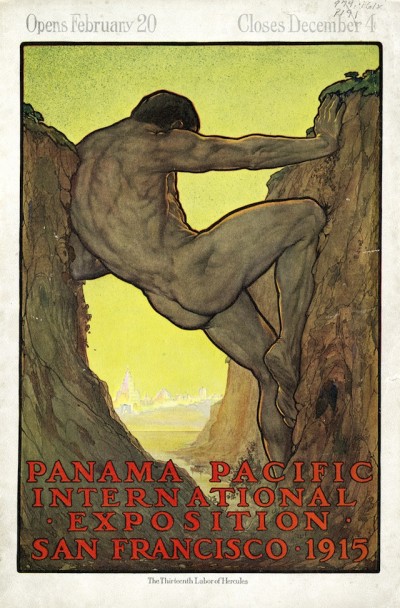

Ostensibly a celebration of the completion of the Panama Canal — an imperial project that overcame malaria, yellow fever, and geography — the exposition more broadly honored the greatness of the United States. A fair poster by Perham Wilhelm Nahl, titled The Thirteenth Labor of Hercules (1915), almost comically suggests that building the exposition was on par with Hercules slaying the Hydra or capturing Cerberus. In the poster, a naked man, washed with muscles, props himself against an enormous canyon wall, moving earth to reveal the “jewel city,” as the PPIE was known.

A triptych of photographic panoramas documents how the site of the fair looked before, during, and after construction (1912-1915). Viewers see the barren flatlands of Harbor View — now the Marina District — transformed into a beaux-arts metropolis. Part of the land the exposition sat on was once an Ohlone trading village, but by February 1915 it resembled more of a Potemkin village. Though The Thirteenth Labor, the grandiose architecture, and the Hellenic statuary gesture towards confidence and power, there is an air of something desperate in the documentation of the fair. The bluster and pomp hints at the need for a young nation to prove its worth to others, as if it is unsure itself.