Solo theater artist Don Reed has an amazing ability to transform himself into characters so memorable and hilarious that there’s no danger of confusing them with each other. When he brings one of them back with just a bit of body language or a signature verbal tic later on in any given monologue, you feel like you’ve run into an old friend.

Reed has turned this knack into a string of long-running solo shows at the Marsh, San Francisco’s hub for monologists. All of his past shows have been autobiographical, chronicling his life decade by decade. The first, East 14th, talked about his teen years in Oakland in the 1970s with his Jehovah’s Witness mother and his pimp father. Subsequent shows have talked about his college years in 1980s Los Angeles (The Kipling Hotel), his ’60s childhood (Can You Dig It?) and his misadventures trying to make it in Hollywood (Semi-Famous).

For his latest show, he tries something new: this time Don Reed himself isn’t one of the characters. Stereotypo: Rants and Rumblings at the DMV is a series of character portraits loosely organized around the theme of prejudice, or at least prejudgments—the assumptions we make about people based on ethnicity, gender, class, disability, religion and other factors. The thin connective tissue is that the nine individuals whose monologues make up the show are all waiting in line at the Department of Motor Vehicles.

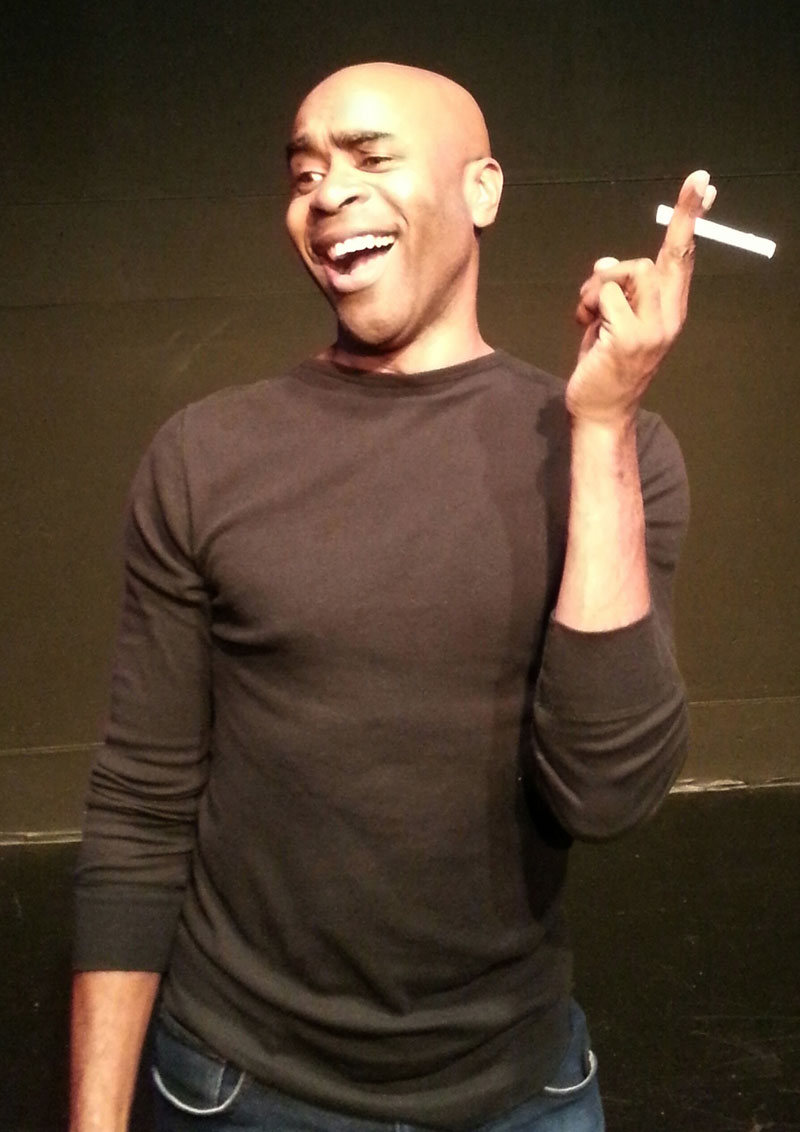

As usual at the Marsh (which runs several different shows on the same stage on different nights), the set is bare: just a few folding chairs and a music stand. Reed wears a neutral ensemble of black T-shirt and pants, occasionally supplemented by an accessory such as a baseball cap over his bald head. His transformations are achieved through performance, not costume. Even the score is largely performed by Reed, who sings wordless incidental music between scenes — although Marie Cartier’s sound design is peppered with recordings, from Gregory Porter’s jazzy “Painted on Canvas” to Panjabi MC’s bhangra-meets-hip-hop “Beware of the Boys.”

The characters in Stereotypo are all recognizable “types,” but the point of the play is that each eventually defies our conceptions of who we think they are and what we think they can do. The young African-American man boasting about all the money he’s making and catcalling the attractive women passing by has a wonderful rant about Waiting for Godot, delivered like a standup comedy routine. A Pakistani cab driver who talks about all the elaborately profane comebacks he has for people who insult him goes on to discuss his forbidden, cross-cultural romance with a black woman.