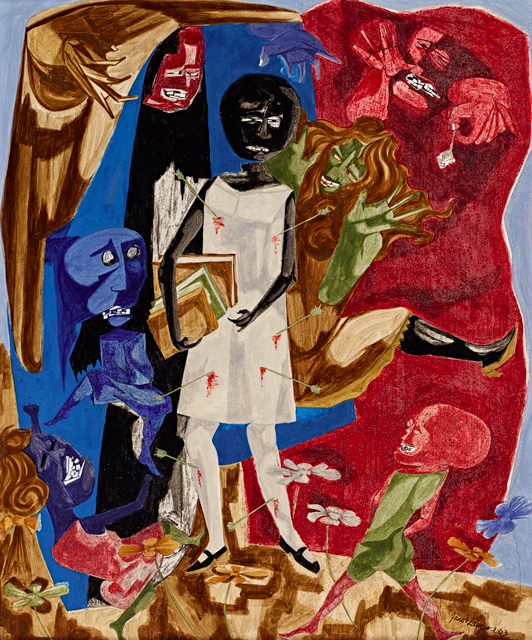

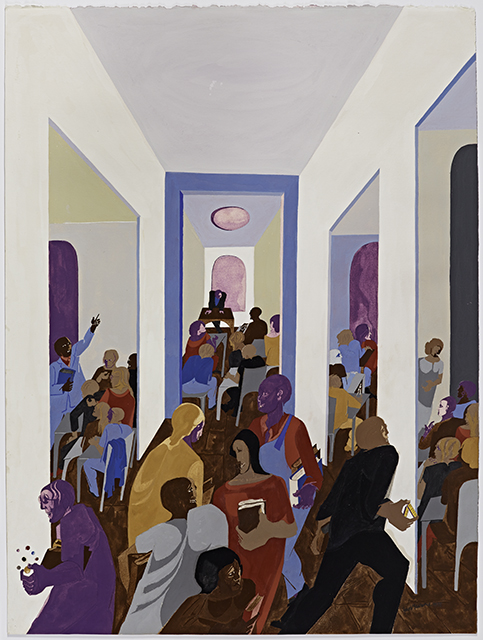

Inside Stanford’s Cantor Arts Center, a newly donated collection of Jacob Lawrence’s work fills a modest exhibition space with bright colors, dynamic compositions and deeply considered artistic documentation of the African American experience. Lawrence’s paintings, drawings, prints and one illustrated book are on view for the first time together, a generous gift to the Cantor from the Kayden family.

Though the collection will remain at Stanford after the exhibition’s close as an unparallelled resource for scholars, art historians and students, Promised Land: The Art of Jacob Lawrence is a unique opportunity to linger with Lawrence’s work. His bold graphic shapes and solid blocks of color translate incredibly well in reproductions, but the small details and surprising shifts in scale that make these pieces so special easily repay an in-person viewing.

For those unfamiliar with Lawrence’s work, I’ll attempt to condense his long and illustrious artistic career. Born in 1917, Lawrence came of age in New York in the final years of the Harlem Renaissance. He attended art classes at Utopia Children’s House, studied with Charles Alston and Augusta Savage, and at age seventeen committed himself to full-time art making.

In 1941, he completed a 60-panel series The Migration of the Negro; in 1943 he joined the coast guard. His long career as an educator began in 1946 at Black Mountain College and ended in 1983 when he retired from the University of Washington, Seattle. His work ranges from the monumental (New York subway mosaics) to the intimate (delicate egg tempera on board). Until his death in 2000, Lawrence depicted historical moments and figures along with utopian visions of possible American futures, blending both into an alternative and egalitarian reality of his own making.

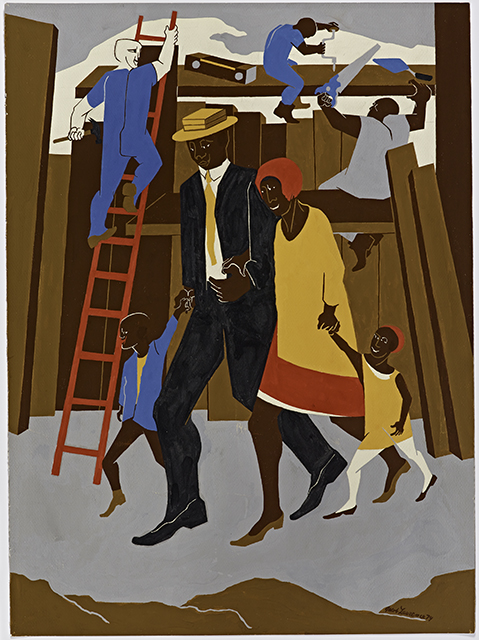

Promised Land is dense, both in the arrangement of artwork and in the scenes Lawrence depicted. His works on paper and board are full to the brim – the eye rarely finds a blank resting space or large swath of solid color. His paintings and drawings are filled with people in motion, at work and play. He routinely depicts scenes of labor: multiracial groups of men working in unison, tools in hand as they erect structures and shape the physical urban environment.

For his 1974 retrospective at the Whitney Museum of American Art, he created a gouache and tempera work on paper to serve as the poster design for the exhibition. Employing a palette of just eight colors, Lawrence depicts a family of four walking past a construction site, their legs criss-crossed, their hands entwined. As Stanford English Professor Michele Elam points out in her catalog essay, “It is important to remember that for most of the twentieth century, representing ordinary people across the color line doing ordinary things, unsegregated and unremarkable, was itself a political act.”