“I see myself with one foot in the Chicana writing tradition and the other foot in a completely different tradition,” she says. “Some of my work speaks really overtly to the Chicana identity. But some of my work is more abstract and harder to place in an ethnic context. When I take a form, it’s hard for me to work in that form without destroying it. I consider it trans-genre — though some people might just call it weird.”

Gurba started out publishing zines and chapbooks, mainly filled with strange, abstract, sometimes grotesque, poetic prose. In her twenties, she completed her first novel.

“It was a monstrous manuscript,” she recalls. “A sprawling and huge story that reflected my childhood.” After shopping the novel around the publishers without much luck, she was asked by someone at Manic D Press about her short stories. In 2007, the indie press released Dahlia Season. In 2011 a collection of poetry called Wish You Were Me came out on Portland’s Future Tense Books. Another poetry collection, Sweatsuits of the Damned, was published by Radar Productions and won the Eli Coppola Memorial Chapbook Prize. She also toured twice with Sister Spit, the queer and radical literary performance group birthed in San Francisco in the late nineties — an experience she calls “invaluable.”

Though she now lives in Southern California, Gurba keeps strong ties to the Bay Area, having lived for six years in Berkeley and Oakland. After graduating from UC Berkeley with a history degree, she worked as an editorial assistant at both Frontiers magazine and On Our Backs, two groundbreaking queer publications published in San Francisco.

For the last decade, Gurba has taught social studies at a high school in Long Beach. “When people find out that I write they assume that I’m an English teacher,” she says with a laugh. “When they see what I look like they assume I’m an art teacher, and when they learn that I’m a social studies teacher, they’re like ‘eeeewww’ and all the horror stories come out.”

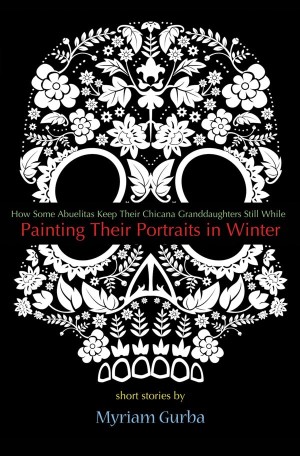

On the subject of horror stories, Painting Their Portraits contains many moments that are utterly macabre. The book’s title story, “How Some Abuelitas Keep Their Chicana Grandaughters Still While Painting Their Portraits in Winter,” has the narrator spending the winter in Guadalajara, in her mother’s childhood home. A painter (just like Gruba’s maternal grandmother), Abuelita tells her granddaughters stories to keep them still during portrait sittings — gruesome tales, involving children made into tamale meat, one-eyed perverts, and a satanic German shepherd that threatens bad children with eternal damnation.

There are also ghosts, like La Llorona, an addition that Gurba attributes to the stories and folk tales that peppered her childhood.

“When you get a bunch of Mexicans together and bring up the subject of ghosts, the stories just spill,” she says. “I’ve always loved that. Even now, when I’m with my family, I’ll bring up the subjects of spirits or ghosts to see what it’ll do to my aunts because I know that I’m going to be entertained for hours. I have all of these folk tales and ghost stories logged in my memory.”

In the end, Painting Their Portraits represents a deeply Mexican experience, one particular to a young, Chicana, queer, nerdy girl with a taste for the shadowy side of life. A girl, Gurba adds, who hasn’t been considered much by the larger literary publishing world as an audience.

“She’s the girl who likes to listen to sad music and wear dark clothes,” says Gurba. “She might be second- or third-generation American. She’s a little bit nerdy but knows she’s not supposed to like school that much. I know that this audience exists, because I’m part of it, and working with kids, I see that audience all over the place. I understand the experience and the taste of that audience, and I understand why they are hungry for stuff that’s a little bit macabre. It makes sense culturally where we come from.”