Pedro Calderón de la Barca’s Life Is a Dream at California Shakespeare Theater is a rare treat. Bay Area audiences seldom have a chance to see one of the great works of the Golden Age of Spanish drama, and it’s never happened at Cal Shakes before.

Less interested than his predecessors in exploring William Shakespeare’s less popular plays, outgoing artistic director Jonathan Moscone added more modern classics to the company’s seasons during his 15 year tenure with the company, such as plays by George Bernard Shaw, Oscar Wilde and Noël Coward. Moscone also started bringing in new adaptations of classic works, like Restoration Comedy by Amy Freed and John Steinbeck’s The Pastures of Heaven by Octavio Solis. In recent seasons Moscone has made a point of bringing more ethnic diversity to the Cal Shakes stage with plays such as George C. Wolfe’s Spunk and Richard Montoya’s American Night: The Ballad of Juan José.

In spite of the breadth of Cal Shakes’ programming, Life Is a Dream is an unusual departure for the company. It’s the theater’s first venture into Spanish drama and only the third time it’s taken on a 16th century classic by someone other than Shakespeare in its 41-year history (or the fourth if you count Freed’s Restoration Comedy), after John Webster’s The Duchess of Malfi in 1979 and Molière’s Scapin, the Cheat in 1998. Life Is a Dream also features an ethnically diverse cast of terrific Bay Area actors.

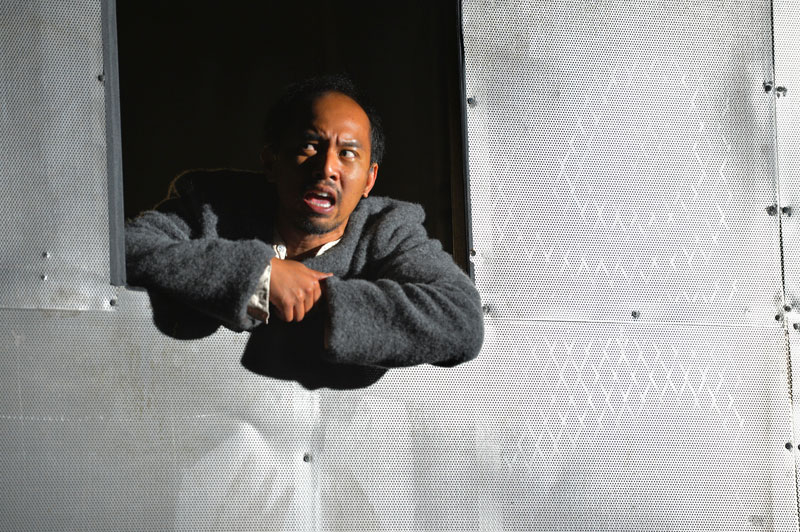

In this 1635 drama, a king (Adrian Roberts, exuding regal gravitas) learns of a prophecy that his infant son would bring doom to the kingdom and his father. So he does what anyone would do: He throws the baby in a remote prison to be raised like an animal in a cage, with his jailer (an eloquent and fretful Julian López-Morillas) as his only human contact. Then he gives his son one chance to defy fate by having the boy sedated and brought to the palace to wake up with all the privileges of princehood. If he proves the prophecy wrong and uses his power wisely, he’ll be allowed to inherit the kingdom. If he abuses the power, he’ll wake up back in prison and be told it was all just a dream, and his foreign cousins (the smooth Tristan Cunningham and Amir Abdullah) will marry and take the throne.

Calderón is playing with a then-common trope of a peasant, drunkard or other “low” person who awakens in a palace to find everyone treating him as royalty. The story goes back at least as far as a tale told about 8th-century Caliph Harun al-Rashid in The Arabian Nights, and William Shakespeare played with the theme in A Midsummer Night’s Dream and in the seldom-staged induction to The Taming of the Shrew. It’s not just a prank in Calderón’s version; the fate of the nation rests on the outcome of this perverse experiment, and it provides an opportunity for a great deal of philosophizing about the nature of life as a dream within a dream.