On occasion, while sitting around a meal at our well-worn dining table, my husband and I like to recall our weirdest favorite childhood foods. As a kid, he loved a heaping plate of sautéed onions. For me, it was mayonnaise sandwiches, compiled quickly after school, to be eaten in front of the television in the mustard-carpeted living room of my home in Whittier, 20 miles east of Los Angeles.

Most if not all of my meals in Whittier were of the modest persuasion. Both parents worked at least one job, sometimes two or three. My mom did her best, usually making sure there was a pot roast or other meat bubbling away in the slow cooker. On nights when she worked late, my dad took us out for fast food. Burritos at El Norte on Whittier Boulevard, pepperoni pizza at Lamppost, and greasy, perfect charbroiled burgers at Rick’s Drive Thru. On special occasions, we splurged on The Grand Canton in Uptown Whittier to feast on what I would later come to understand as Americanized versions of Chinese food: a syrupy sweet-and-sour chicken and salty chow mein, followed by my favorite dessert of crumbly, sweet almond cookies.

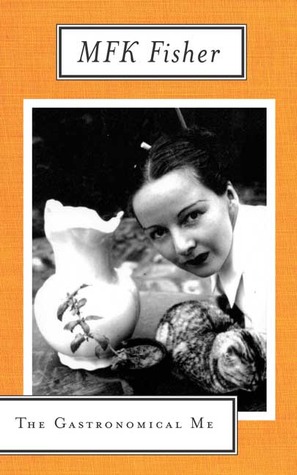

It was on these same Whittier streets, 70 years prior, that M.F.K. Fisher (the author of 27 books, including the classics The Gastronomical Me and How to Cook a Wolf) had her first experiences with hunger and the seductive pull of food. The “poet of the appetites,” as John Updike called Fisher, may have spent her last years in Glen Ellen at a cottage near Sonoma in the Valley of the Moon, but her formative years were spent in Whittier, a modest town founded by Quakers in the hills above Los Angeles.

As you might imagine, given its stolidly religious origins, Whittier, unlike Sonoma, is not the stuff of foodie fantasy. At least, not the Whittier where I grew up, and certainly not the post-Victorian era version in which Fisher lived with her family. Her father Rex owned the Whittier Daily News, and for many years, her ascetic, severe grandmother ruled the meal planning with demands for bland white sauces and plain puddings. (The woman’s favorite meal, according to Fisher, was steamed soda crackers with hot milk.) It was only later, when Fisher struck out for Dijon, France at the age of 21, with her new husband Al, that she discovered the joy of hedonistic gastronomy, an experience beautifully captured in her many essays.

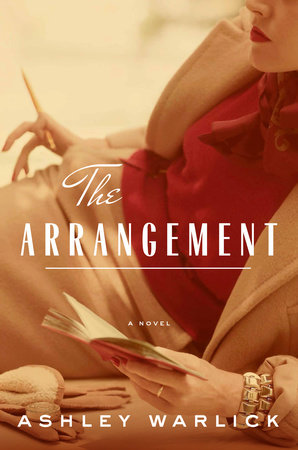

M.F.K. Fisher’s life story has received no shortage of coverage, given her prolific writing, and a few well-received biographies. In her fourth and latest novel The Arrangement, Ashley Warlick becomes the first writer to fictionalize the culinary star’s life. As the editor of Edible Upcountry, a South Carolina food magazine, Warlick knows that some of the best stories can be found in food. Accordingly, she does a fine job of weaving together food and romantic intrigue into a readable, if somewhat light, story.