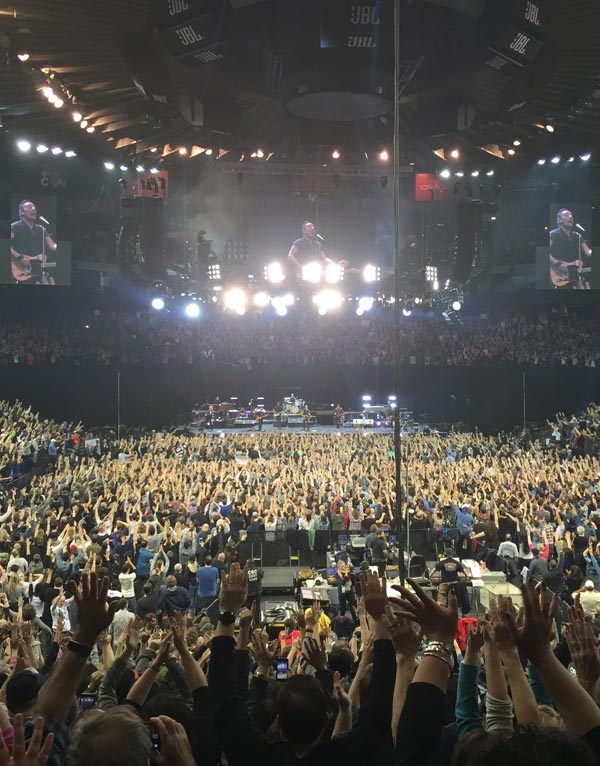

Bruce Springsteen decided to do a strange thing last year. He’d go out on his first tour in three years, he announced, and instead of a setlist culled from a huge back catalog, he’d play in its entirety The River, an album that maybe 10 percent of his fan base would pick as the one to hear live, beginning to end. (Only two songs from The River cracked the top 35 Springsteen songs in a recent fan poll.)

At the time, Springsteen explained this decision by saying, essentially, that he wanted to get the band on the road before a planned solo tour, and since he had a new box set of The River just out — and since he’d always imagined The River as a rollicking party reflecting the pacing of the band’s live show — well, why not?

But by the time The Boss got to Oakland last night, two months into ‘The River’ tour, his reasons had grown more serious-minded. I went to the show eager to see if I’d have a different reaction to the album live, if I’d see a different version of myself reflected in its songs or if I could appreciate the album as a whole in a new light. But from the onset, Springsteen himself was all too eager to provide us with a new framework.

“The early records were kind of outsider records. We were all part of a marginal community on the streets of Asbury Park,” he said, before the album’s first song. “But by the time I got to The River I was trying to find my way inside. I’d taken notice of the things that bound people to their lives — the work they choose, their partners, their families, their commitments. I wanted to imagine and I wanted to write about those things, and I figured if I could write about ’em I’d get a little closer to havin’ ’em in my own life. I wanted to make a big record. A record that felt like life.”

This meaningful intro speech of Springsteen’s — about making the album to “get a little closer to the answers” — felt like awkward revisionism. The River is basically a big, commercial-sounding double album with a lot of filler, containing exactly three types of songs: catchy 1-4-5 rockers, dripping ballads, and a few roadhouse ramblers. Why paint it as an important universal-theme album? Why try to make The River step in line with its weighty predecessors, Born to Run and Darkness on the Edge of Town?