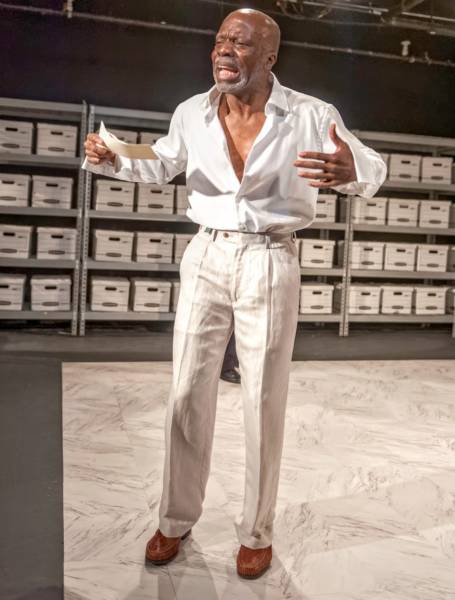

Watch Carl Lumbly’s face in SF Playhouse’s production of Red Velvet, and it seems as if you can read hundreds of distinct variations of despair, hope, and dismay in it. Lumbly gives an amazing performance in Lolita Chakrabarti’s backstage drama about the rise and disillusionment of the 19th century African-American actor Ira Aldridge (who wowed U.S. and British audiences with his portrayals of Shakespearean characters such as Othello) — or, maybe better put in this play about actors acting, a performance of a performance.

Now let’s slip across town to the Buriel Clay Theater in San Francisco’s Western Addition neighborhood for a moment so that we can catch L. Peter Callender, the brilliant actor and artistic director of the African-American Shakespeare Company, playing a live-wire Mark Antony in Antony and Cleopatra. The great Roman general’s position is precarious — he wants to live and love and rule in his own way, to openly cavort with Cleopatra and maintain his position in the Roman hierarchy of power. As Callender’s Antony falls, you can’t help but feel his descent in racial terms when personified by a black actor. And it stings all the more.

What unites these two productions is the fear that race — or blackness, really — is a kind of performance that is always on the verge of disrupting everything around it. As an abstraction or idea, race is fairly static. But let a performer, a politician (Antony) or an actor (Aldridge) loose, and all of a sudden those abstractions become dynamic and threatening.

When Aldridge replaces the great and gravely-ill English actor Edmund Kean in the role of Othello, he walks into his first rehearsal with Kean’s company as if nothing could go wrong. He’s only there to get to know his fellow cast members and yet he knows how fraught this meeting will be. Caught between the contradictory impulses of hope and knowledge, Lumbly catches the awkwardness of this painful encounter — the tilt of Aldridge’s shoulders, the way his eyes are always surveying the entire sweep of the stage, his awareness of how his body unsettles everyone around him — with immense subtlety and pathos.

Meanwhile, in Antony and Cleopatra, the most unsettling body is Cleopatra’s, and yet it is Antony’s body that goes through the most profound transformations. In Egypt, he behaves as if he were a Greek god descended from the heavens to once again taste the pleasures of the earth; in Rome, he is less than human and more the personification of political will and power. Callender embodies both states so fully that you see traces of one in the other. It is as if Antony is suffering a psychic split right before us, constantly and without end.