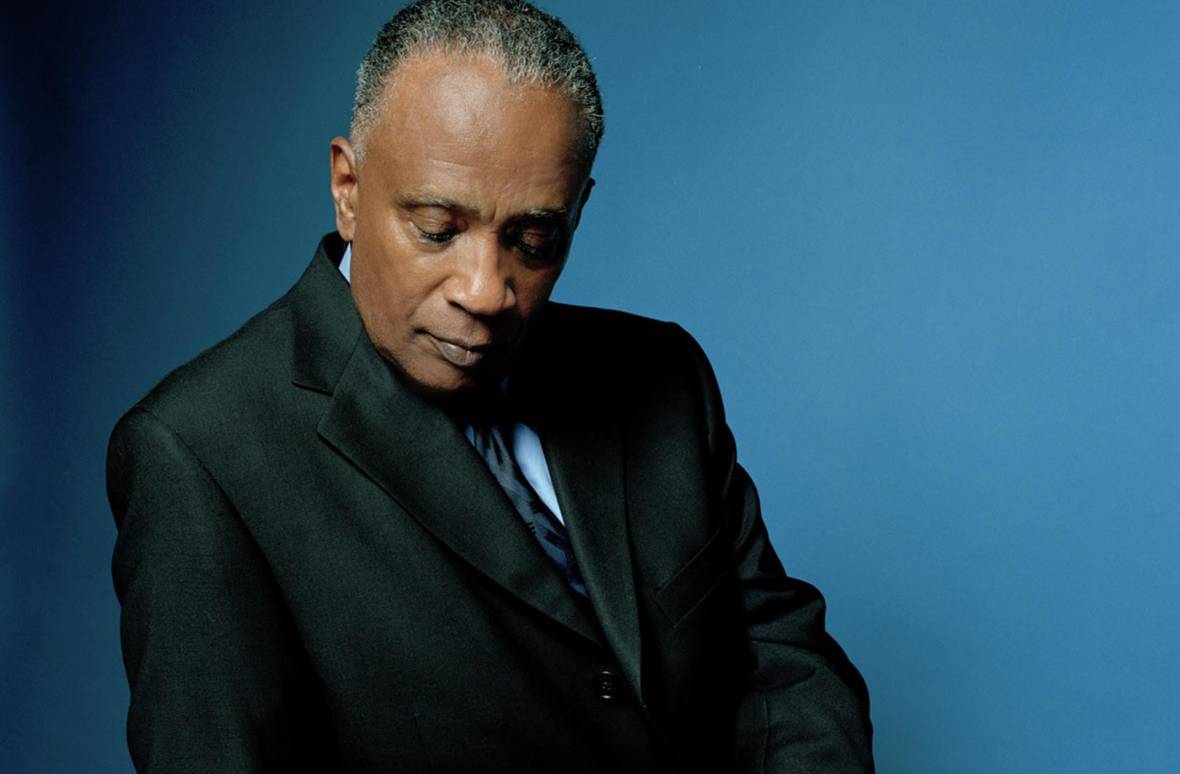

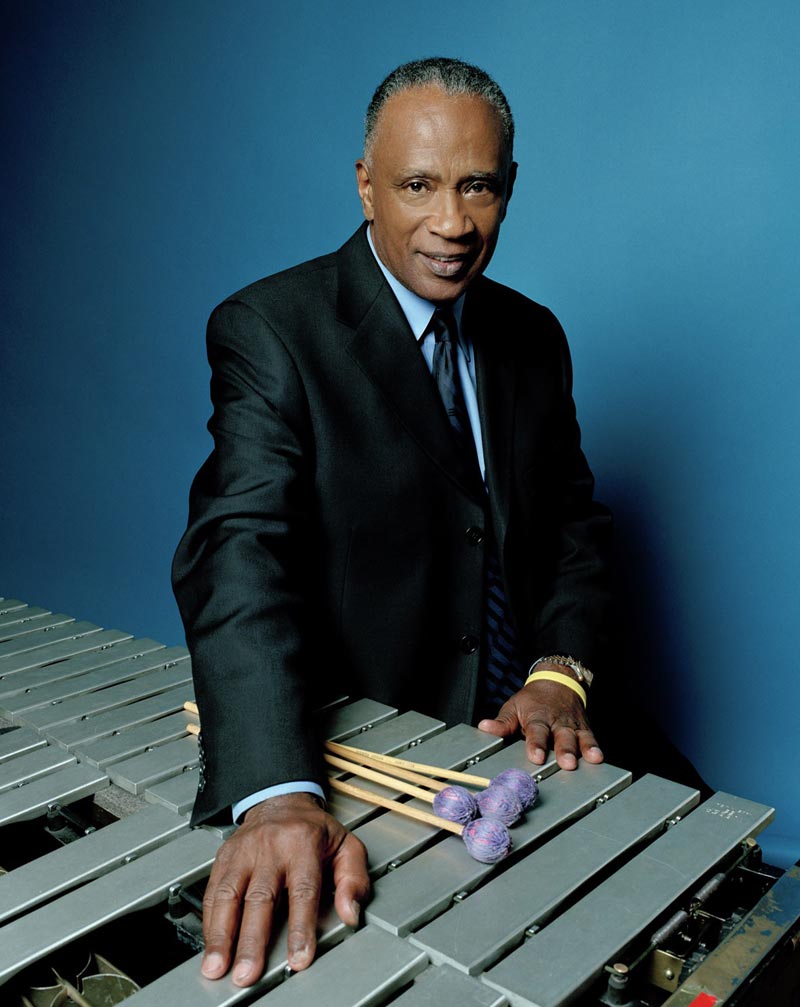

Vibraphonist Bobby Hutcherson, an NEA Jazz Master who influenced generations of musicians as an improviser and composer, died Monday at the age of 75 after a protracted struggle with emphysema.

A longtime resident of the seaside hamlet Montara, about 20 miles south of San Francisco, Hutcherson grew up in Pasadena and made a name for himself in the early 1960s as a creative catalyst for a cadre of brilliant young musicians associated with the Blue Note label. As a composer, bandleader and recording artist, Hutcherson created a body of work that ranks among the most profound and widely celebrated in an often divisive era marked by a proliferation jazz aesthetics.

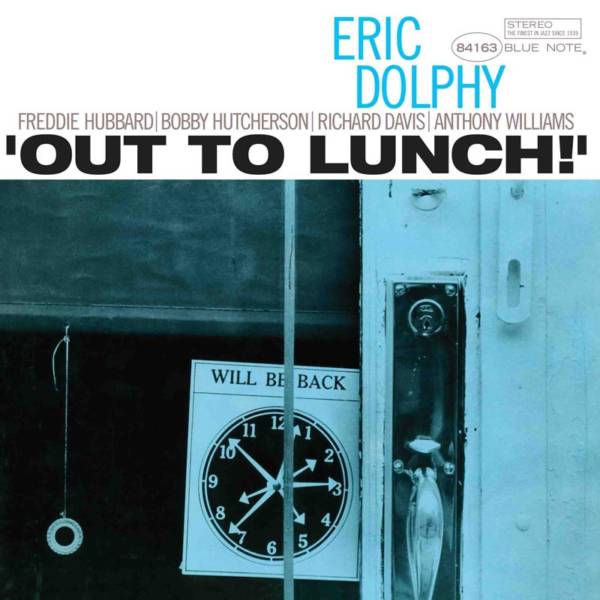

Introduced to the Blue Note fold by veteran alto saxophonist Jackie McLean, Hutcherson quickly joined a loose confederation of creatively ambitious New York musicians inspired by the rhythmic and harmonic innovations of free jazz patriarch Ornette Coleman but dedicated to experimenting with compositional form. With his thick, ringing four-mallet chords and exquisitely chiseled melodic lines, he played a defining role on several dozen era-defining albums, such as Eric Dolphy’s Out To Lunch, Lee Morgan’s The Procrastinator, McCoy Tyner’s Time For Tyner, Joe Henderson’s Mode For Joe, Tony Williams’ Life Time, Grachan Moncur III’s Evolution, and McLean’s One Step Beyond.

“Jackie McLean opened up a whole world to me, and during those years in New York I was running into all these players and recording all the time,” Hutcherson told me in an interview several years ago. “It seemed like everybody had an original sound. Everybody was writing music and the world was going crazy. It seemed like everywhere you went there was just unbelievable things, the war, riots, assassinations, and the music was definitely a reflection of everything that was going on.”

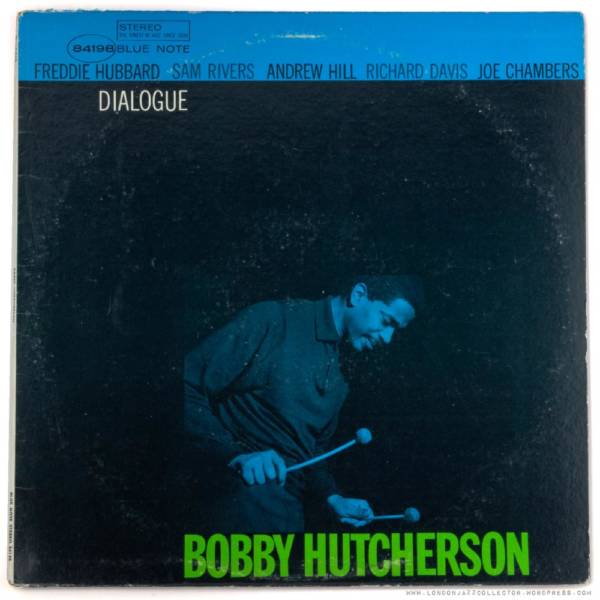

During his 13 years with Blue Note — a tenure exceeded only by pianist/composer Horace Silver — Hutcherson recorded a series of classic albums under his own name, including Dialogue, Components, Medina, and Stick Up! He had arrived in New York City in 1962 with a band led by Al Grey and Billy Mitchell and ended up driving a cab when the group broke up. He credited his fear of returning home to Los Angeles as a failure with pushing him to jump into the experimental-minded post-bop fray, where every recording seemed to introduce a new harmonic vocabulary.