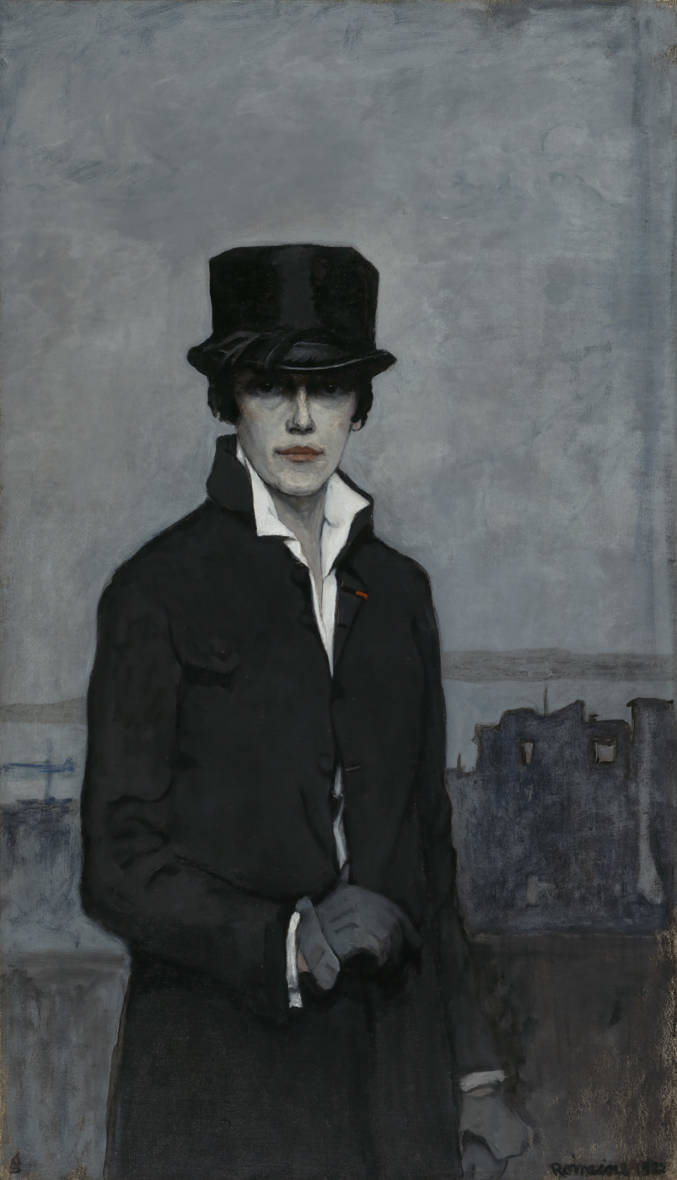

Twentieth century painter Romaine Brooks introduces herself in a 1923 self-portrait: She wears a narrowly cut, long, black riding jacket with a white blouse. She has short cropped hair, and her eyes are shadowed by a black high hat. There’s the slightest smudge of maybe pink on her lips — otherwise the whole portrait is black and various shades of gray.

An American who lived in Paris, Brooks conveys loneliness, strength and vulnerability, says Joe Lucchesi, consulting curator of an exhibit of Brooks’ work at the Smithsonian — “a kind of careworn but very strong presence all combined in one.”

Brooks painted androgynous women and depicted nudes so melancholy they’d make Renoir’s pink ladies weep. She left most of her work to the American Art Museum, where her work is currently on view.

The women she paints share a severe palette and a certain mood. In their man-tailored jackets, their aesthetic sensibilities, their intense love relationships, Brooks’ women moved in the artistic circles of 1920s Paris. Poets, novelists, socialites, photographers and painters, they were fashionable and rich. Their money helped insulate them from social constraints of their day.

In Brooks’ case, money freed her to paint whatever and however she wanted — the unconventional, androgynous women, the limited, gloomy palette — and to ignore what her Big Guy contemporaries were doing — Picasso and Matisse, whose vivid and revolutionary canvases filled the homes of Gertrude Stein and family.

9(MDAxOTAwOTE4MDEyMTkxMDAzNjczZDljZA004))