All musicians use some technique to get the music in their head onto the page. Most use modern notation, with the standard five line staff. China’s notation system uses numbers instead of round notes. Country musicians might use the simplified, chord-centric Nashville number system.

Trumpeter Ishmael Wadada Leo Smith felt constrained by the notation methods he encountered. So he developed his own.

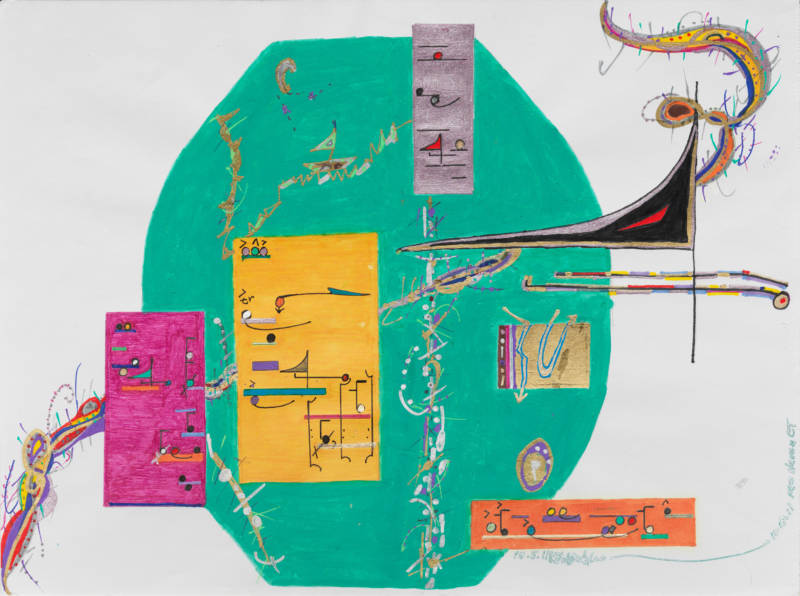

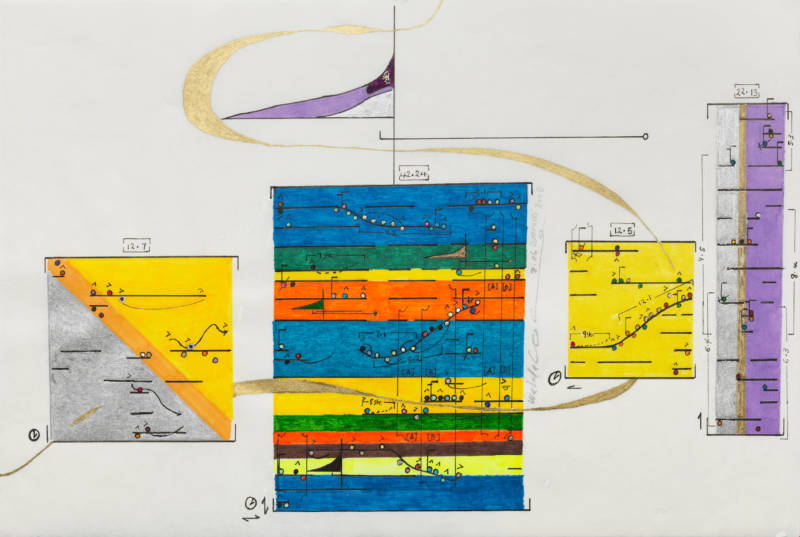

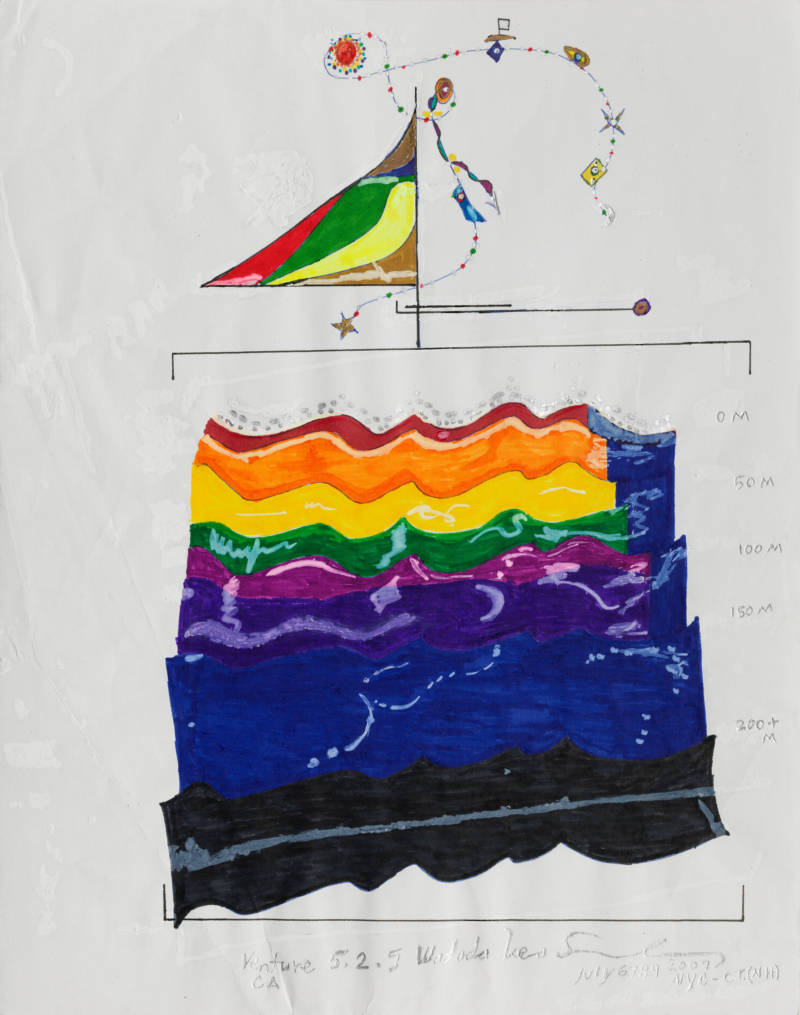

Smith, 74, calls his method Ankhrasmation, a term created from the “Ankh,” the Egyptian symbol for life; “Ras,” the Ethiopian word for leader; and “Ma”, for mother. Ankhrasmation combines symbols, colors and lines to illustrate Smith’s abstract, ambitious jazz. The result, on exhibition Dec. 14 at the Kadist, looks like something you’d find in your Abstract Art for Dummies book. But Smith is adamant that it’s not simply a visual score. He also chafes when I ask if it’s a framework for improvisation. So what is it?

“The easiest way to think about it is that scores are constructed in a way that can be used to produce music, but the music itself is not on the score,” Smith says. “The score is this doorway where you become aware of elements like structure, shapes, color and [the] connection of those shapes and colors and lines and dots. You have to transform that into some kind of reference, [and] then you’re able to actually get to the music.”

Ankhrasmation’s combination of creativity and structure has underpinned Smith’s long, impressive career. He grew up playing Delta blues in Mississippi, and in the sixties, he became a member of Chicago’s Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians, which helped shape the sound of modern and avant-garde jazz. (Initially, it was rough going: elders hazed Smith by talking through his initial performance). There, he honed his style of expressive, boundary-pushing free jazz, which has now appeared on the more than 50 albums he’s released. As he got older, he became a Rastafarian, adding Wadada to his name, and then converted to Islam, adding Ishmael. He started racking up awards, becoming a Guggenheim Fellow in 2009 and a 2013 Pulitzer finalist for his album about the civil rights movement, Ten Freedom Summers.

He started creating Ankhrasmation in 1967. To him, none of the traditional notation styles incorporated the musician’s life — their internal experiences, emotions and references — so he started researching, digging through other musician’s scores and music history books. He came up with the building blocks of Ankhrasmation, a series of units which includes rhythm-units, improvisation-units, and velocity units, which dictate the speed of a piece. Musicians study an Ankhrasmation piece and determine for themselves what the colors and symbols — things like eyes, boats and pyramids — mean to them personally, and then bring that knowledge with them to a performance.