“He wasn’t sad about it,” adds friend David Droz. “It was more like, he had come to this understanding both philosophically and scientifically that existence was without any higher meaning.”

“That was a huge conclusion for him to come to, because even as a kid he had lived his life trying to add purpose and meaning,” Klepper says.

Both Klepper and Droz say their friend came to this understanding during a particularly harsh summer in Cambridge, where he was isolated from friends and under immense academic pressure.

“We used to Skype a lot, and he would always say the only thing he was working for at Cambridge was one test,” Droz says. “So everyone was inside, it was raining, he was away from his friends, and he was feeling really, really lonely.”

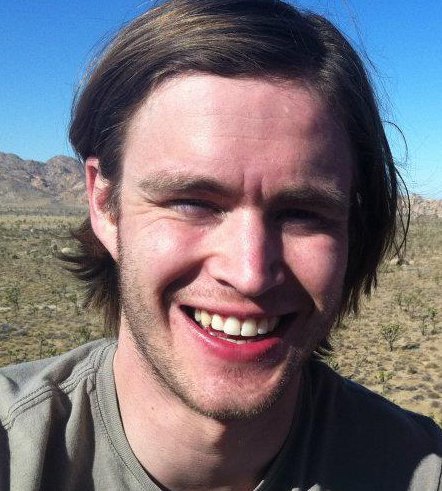

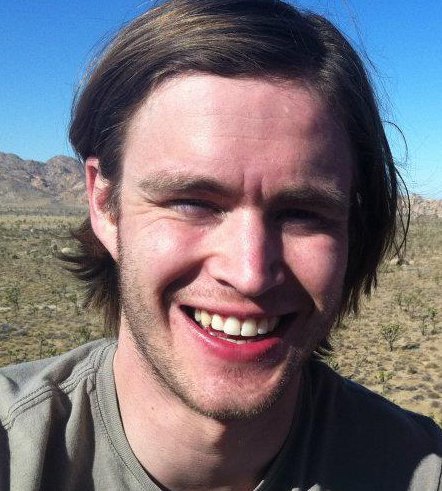

When he returned to the U.S., Walrath carried around his personality and existential understanding with him in every part of his life — even on his OK Cupid profile. Walrath refused to mention his notable achievements, and he often found it difficult to satiate his desire for a deep level of connection with the few dates he did attract.

“I had to write his OK Cupid profile, and once I bragged to everyone what kind of guy he was, he would get dozens of messages a day,” Klepper says. “It was nuts.”

One of the people he met online was Alexis Abrams-Bourke, a loquacious and curious young woman who was quick to ask Walrath, “Why take life so seriously?”

And while Walrath struggled at first to be as effusive and talkative as his new friend, he found in Abrams-Bourke a partner who brought out an energetic goofball side that had laid dormant while he sought out cerebral, high minded questions.

“When I met him he was a solid nihilist libertarian,” Abrams-Bourke says. “Although he didn’t tell me he was a libertarian. If he would have told me he was a libertarian, I would have run away.” Abrams-Bourke says the couple connected on a playful level. “He had this high-pitch giggle which you wouldn’t expect from a six-foot-two, big dude,” Abrams-Bourke says. “I can remember early on in the relationship, we were trying to figure out what we were doing. And he said, ‘I can be so goofy with you.’ It wasn’t the only reason, but we connected on this deep, playful level, and over time I was watching him become more and more spiritual, and finding more and more meaning in his life through love and his relationships.”

Recently, Walrath had joined the firm Durie Tangri LLP, which remembered him in a statement as “a fine lawyer as well as a good and caring person.” Previously, Walrath had clerked at the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of California and the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals.

On the night of the Ghost Ship fire, Abrams-Bourke invited her boyfriend to a magazine opening in San Francisco. Walrath decided to stay close to their Oakland home instead. “I think he hoped I would come home early and we could hang out,” Abrams-Bourke says. “But I texted him and told him I was going to this party, and so he was looking for something to do.”

Ultimately, Walrath decided to bike over to the underground music and art show on 31st Avenue in Oakland.

At 11:25 pm, Abrams-Bourke got a text from her boyfriend. “Fire,” it read.

A split second later, Walrath sent the last text of his life.

“I love you,” he wrote.

Abrams-Bourke says she, too, thought of Walrath as a sort of superhero, someone who wouldn’t ever die. “Immortal,” as she puts it. Abrams-Bourke says she can’t make sense of why he didn’t escape the warehouse. She thinks the fire must have come at him quickly for his text messages to have been so short.

“That’s what he chose to do, send me a text,” Abrams-Bourke says. “I know he wanted me to know he loved me, and what had happened. But now I want a why. I want to believe in something more, but I don’t know if I do… I wish he was here, because he could help me figure this out.”

For more of our tributes to the victims of the Oakland warehouse fire, please visit our remembrances page here.

For a printable poster of the illustration above, see here.