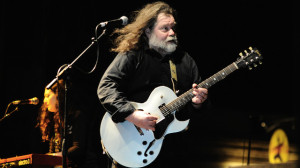

When Roky Erickson takes the stage of the Great American Music Hall on August 22, 2013, it won’t be the first time the Austin, Texas, singer-songwriter has headlined in San Francisco. For the record, he played the same room as recently as last year, and in 2010 he performed at the Fillmore Auditorium after an absence of 44 years. The last time he graced that legendary stage, August of 1966, Erickson and the 13th Floor Elevators were beginning a three-month-long Bay Area run that included stops at the Avalon Ballroom (on various nights, the band’s openers included the Sir Douglas Quintet, Quicksilver Messenger Service and Moby Grape) and Bill Quarry’s fabled Rollerena in San Leandro.

Back then, the prototypical psychedelic rock band (whose sound was somewhere between the surf-stylings of Dick Dale and the Rolling Stones during their R&B-cover-band years) was at its peak. Its first and only hit single, “You’re Gonna Miss Me,” written by Erickson, was starting to get airplay, and the band’s highly influential debut album, The Psychedelic Sounds of the 13th Floor Elevators, dropped in November that same year.

“That was a pretty good while ago,” Erickson says by phone, in response to my predictable question about what it was like to play in San Francisco back in the day. In fairness to Erickson, most of us would probably struggle to recall the events of almost half a century ago with anything resembling clarity (I’m hazy about last week). And most of our memories are not anywhere near as clouded as Erickson’s, who consumed almost religious quantities of LSD during his handful of years with the Elevators and received numerous forced sessions of electroshock therapy while an unwilling resident of the Rusk State Hospital for the Criminally Insane. The reason for his “One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest” experience? Busted for a single joint and facing 10 years in a Texas prison, he pleaded insanity, which turned out to be a truly crazy thing to do.

“They had Country Joe and the Fish,” Erickson finally answers in a friendly, gravelly voice, “and Big Brother and the Holding Company and those Grateful people. I would just kind of stay out of their way so they could make their music, to find out what they were trying to get at. They’d have about as many bands you’d want up there,” he adds of the multi-band marathons that often typified shows at the Fillmore and Avalon. “It was rather dangerous, you know?”