Art historians and curators offer disparate explanations for Stuart Davis’ absence from the list of American artists who are “household names.”

Stuart was ahead of his time, say some. His paintings bridged modernism and pop, but they weren’t quite one or the other, say others. There hasn’t been a major retrospective of his work in 20 years, goes the more recent argument; many of his paintings, now fragile, rarely travel.

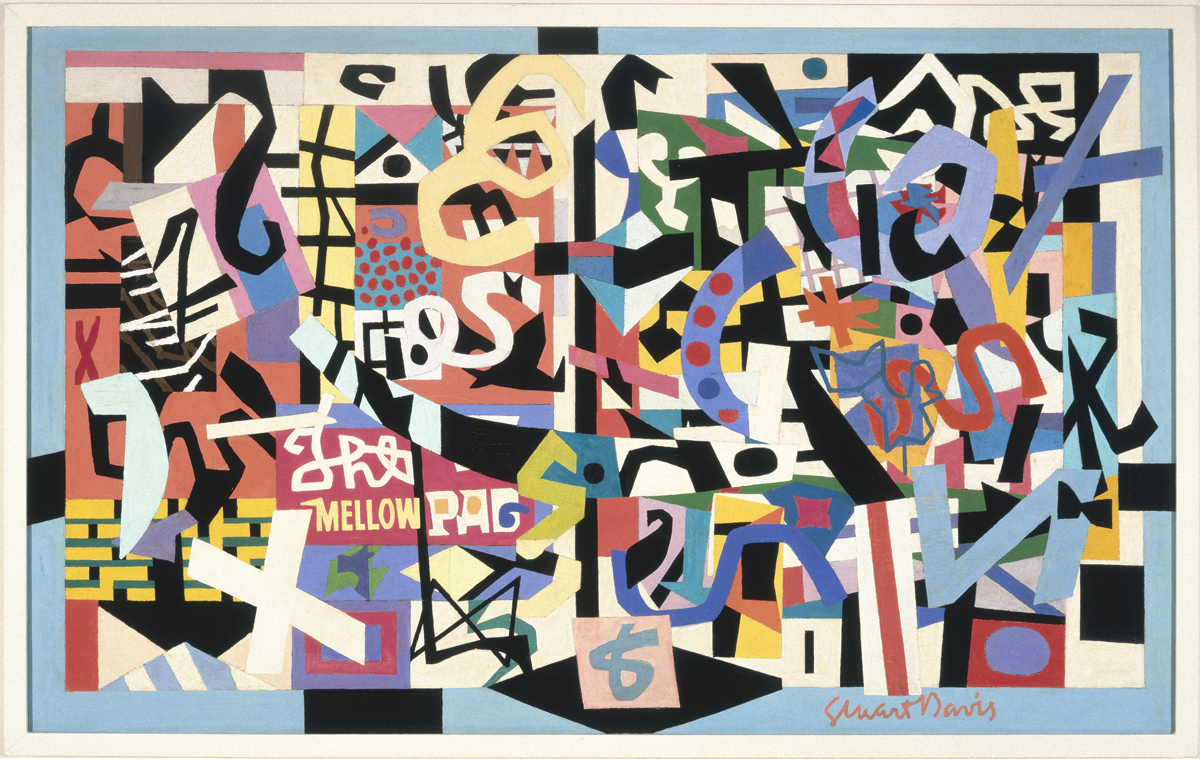

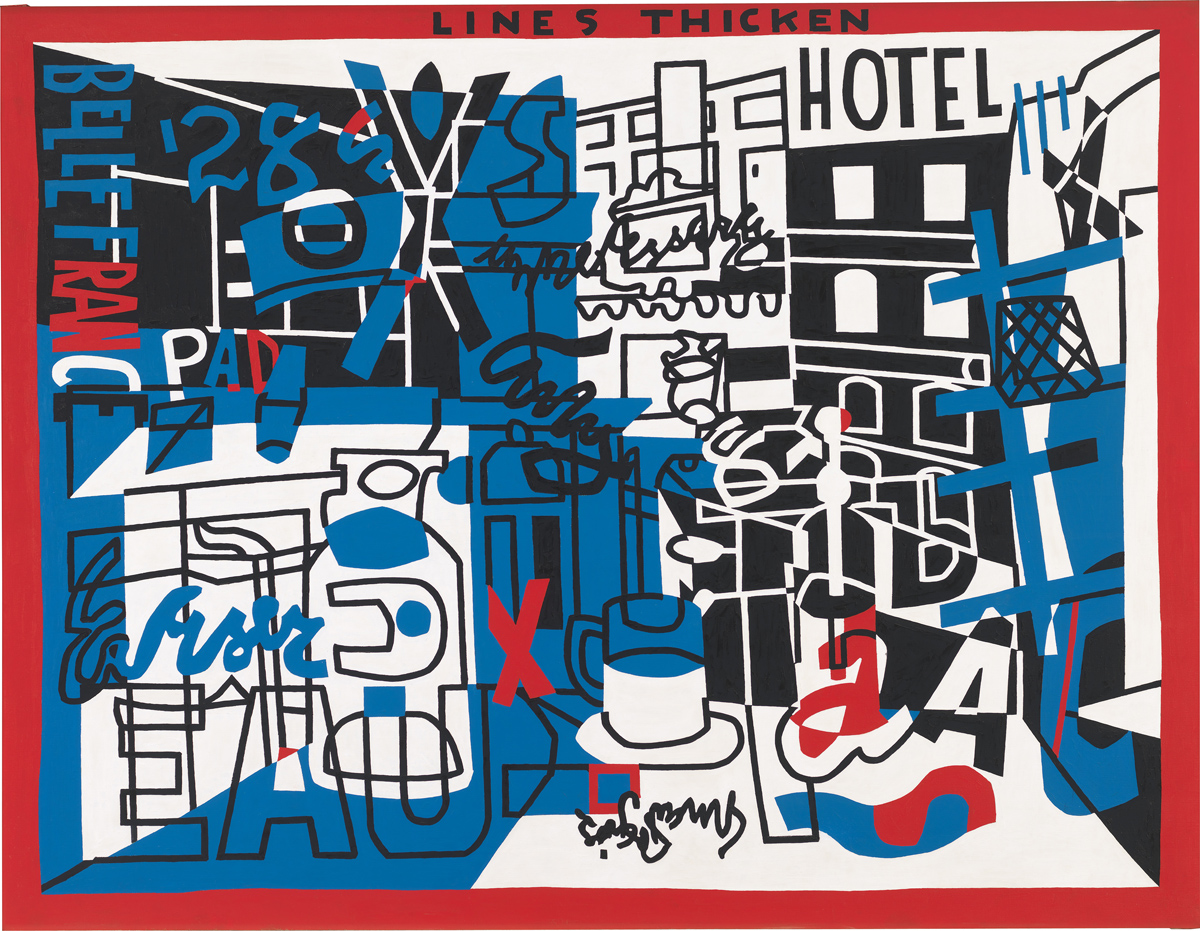

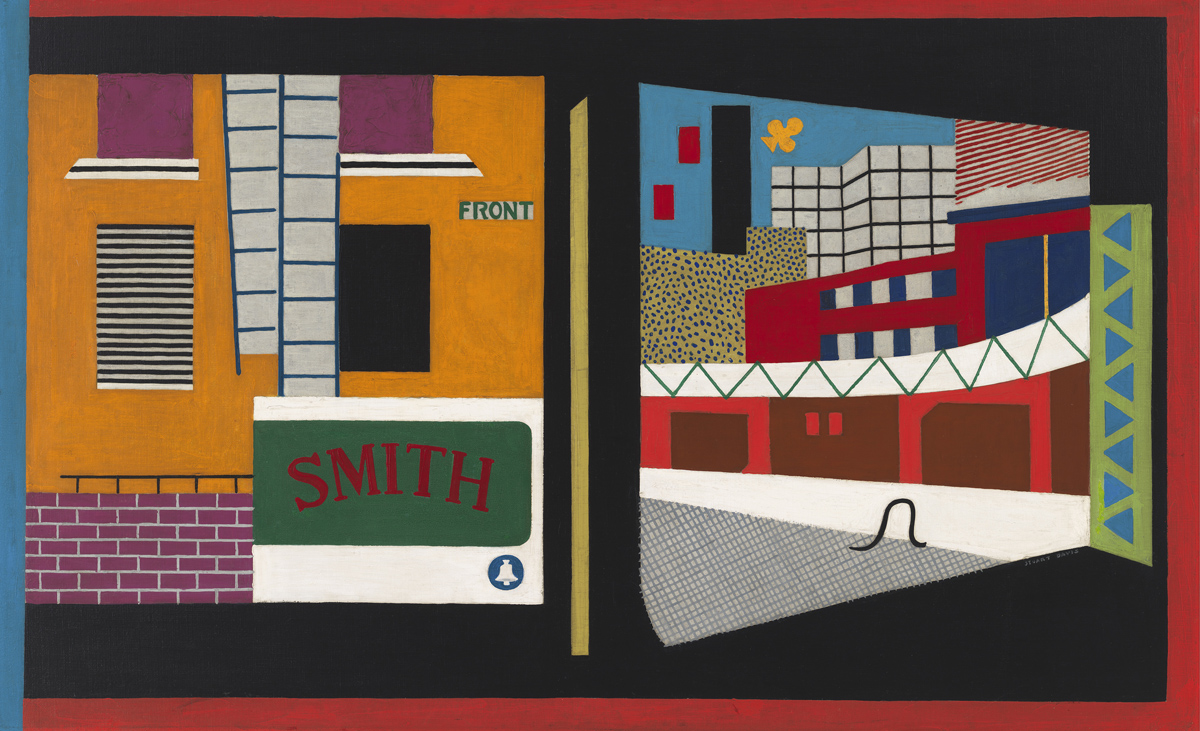

But really, there is no excuse: Stuart Davis should be a household name. Stuart Davis: In Full Swing, opening Saturday, April 1 at San Francisco’s de Young Museum, works hard to prove that point, packing 43 years of hard-edged color, overlapping shapes and enigmatic text into just one second-floor gallery space. (The museum’s main blockbuster for the months to come will be The Summer of Love Experience, opening Saturday, April 8, but more on that next week.)

Born in 1892 in Philadelphia to artist parents, Davis pursued art from an early age, dropping out of high school (with his parents’ blessing) to study painting with Robert Henri. The Henri School’s philosophy that “art cannot be separated from life” greatly appealed to the hard-drinking, jazz-loving teenage Davis. In later life, the artist reportedly kept the television on constantly with the sound off, to stay abreast of commercial imagery.

In Full Swing begins with some of Davis’ earliest abstract works — paintings of Lucky Strike tobacco boxes and Odol mouthwash jars — rendered in a synthetic cubist style that flattens text and texture to the canvas surface. The muted tones betray none of the artist’s future love for the whole spectrum of colors, but Davis’ subject matter is decidedly populist, from the details of printed packaging to the racing results in the sports pages.

Additional prologue is provided by Davis’ 1927-28 Egg Beater series, a suite of four paintings (three of which are on view at the de Young) made possible by a $125-a-month stipend Davis received from sculptor and heiress Gertrude Whitney (yes, that Whitney). The still lifes feature an electric fan, a rubber glove and the titular egg beater as solid geometries that Davis merged with color and line to the architecture around them.