What was the genesis of On to the Next Dream?

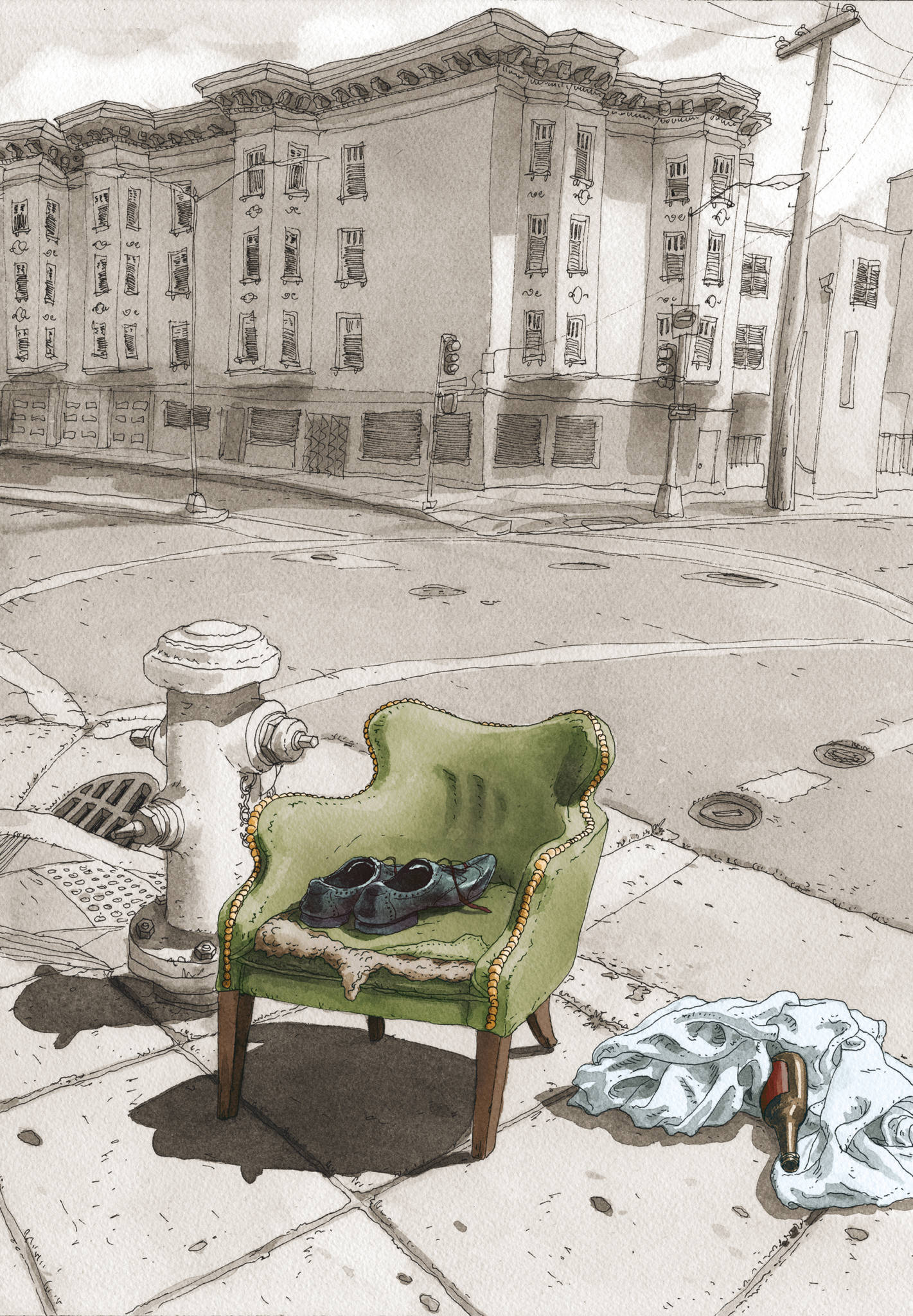

When the eviction came, it was an emotional and stressful situation and I found myself wanting to talk about it. I wrote all of these first-person pieces but I would scrap them at the last moment. At midnight before deadline, I was calling friends and asking them to give me feedback, and I had never done that before with All Over Coffee pieces. But then I realized I could use seemingly real situations and keep taking them one step further — an absurdist approach. Because I thought, right, that’s what we’re feeling, the anxiety and the absurdity.

So amplifying true situations with absurdity allowed you to enter into the creative process?

Exactly. I had this rule for myself that I would begin with a normal situation and then just turn up the volume increasingly until it was ridiculous. In the second chapter, the character goes next door to a house sale, and he realizes that it’s not actually the apartment they’re auctioning off — it’s the box in the corner. I thought that was a simple, clever metaphor. Nothing so outrageous, in terms of calling a small space a box. We do that all the time. But I thought it was humorous. And then I got emails asking whether that had really happened.

It’s a sign of the times that some of your readers thought the story about the box was actually true.

You hit on the exact thing that I want to talk about. Which is that we’ve become desensitized to absurdity, and that happens incrementally. When small things happen over time, you wake up years later and realize that you’re living in a completely absurd situation — but you don’t think so anymore. The line I like to use is, “I lost miles by slipping inches.” That’s what the box showed me. And the absurdist metaphor was a big change for All Over Coffee. It had never been a part of the toolbox that I allowed myself.

I like a limited palette — physical with my drawing materials and stylistically with my writing materials. All Over Coffee was always about this simplicity of language and scenes. As I began to write more flash fiction pieces, I allowed myself more tools. The metaphorical tool became something different because I was making a statement: I’m showing you this for a reason. I was very aware that I was taking a different step. These stories lead you to a specific spot rather than opening a door for you to wander out of.

You spent so much time illustrating San Francisco and capturing this specific energy. How did it feel for you to get that eviction letter?

There’s a scene [in the new book] where I’m in the coffee shop and people’s faces are disappearing and the woman across from me can’t understand me because she’s a long-time San Franciscan whose family owns property. In that chapter I was saying, “You know, I feel like this is partially my fault.”

The word eviction carries a lot of shame. In any place else but San Francisco, or maybe Manhattan, if you say you’re evicted it’s like, “Wow, what did you do? Your place must be infested with animals and you haven’t paid rent in a year and you must be a despicable person if that happened to you.” Anyone who lives in these highly charged urban environments knows that’s not the case. But there’s still this undercurrent. A feeling that people think: “Oh, you clearly didn’t take care of your life or this wouldn’t have happened to you.”

[The eviction] made me look at my definitions of success. Up until that point, I’d been fairly successful. I’d published two books, I was working on my third. I was selling artwork. I was making a living as an artist and a writer, and I had been for more than a decade. Which is not an easy task, and it took me many years to get to that point. I felt like I was living the life I wanted. I mean, I wasn’t able to buy a home in San Francisco, but my energy wasn’t focused on that. A lot of the money I made I would put it back into my work. Suddenly, when I was losing my home, I thought maybe I had my priorities wrong. How successful was I really if I couldn’t even secure a place for myself to live in a city, when I’m one of San Francisco’s creative people? I had to go through a period of thinking this was all my fault.

At the same time, by translating the experience into a story, I didn’t want it to be “my story.” It’s really not about what happened to me. It’s fantastical. I mean, my wife isn’t even in it. If I were really to write the story of what happened there would be a lot of sincere moments of what we went through, and how we dealt with it emotionally.

My wife and I went to a meeting down in the Tenderloin shortly after receiving the eviction notice. We walked into the room and there were hundreds of people there. We spent the afternoon listening to stories of people who were losing their homes, entire buildings of people who were being evicted. We left there saying, “We don’t belong here. All of those people were far worse off than we were.” There were people who had service jobs, who had families, English was their second language, they weren’t rooted in the community in the same way that we were, they had less options. Sure, we weren’t buying a home in Pacific Heights, but we weren’t about to fall out on the street either. We really felt like we were in the middle. It was like we didn’t belong in either world. People were saying, “You should be the face of eviction,” but I rejected that because I thought it was unfair. And it wasn’t my cause.

I had to wrestle with questions like: Who are you? What do you want to do? It forced me to ask a lot of these questions that I thought I had answered. I realized that was the common thread: We all feel powerless in the face of something.

Another idea that comes up is that change is inevitable. San Francisco has always been a boomtown, and a particular instability arises from that. But your character also says that it’s not okay that people are being displaced. And how do you reconcile those two realities?

You know, talking about the eviction is easy, but ultimately I feel small if I’m out there saying, “This is the book about me being evicted.” What it’s really about is how I learned how to take an emotionally charged loss and how I learned to process it in a way where I could make something. I grew as a person, but also as an artist. Week by week, I was able to take crazy emotions and translate them into metaphors, and deliver them to an audience. I used the process of art to deal with my emotions and and give them to the world as a way to survive the experience. And those words sound extreme, because I feel like there’s far worse suffering in the city.

Eviction is a big deal, though. I wouldn’t underestimate how much it can upend your life.

Ultimately, it’s about how we deal with loss and change. I also realized that I couldn’t go back to All Over Coffee as it used to be when this story was over. That’s when it dawned on me that I wasn’t just writing about the end of the era in the Mission, I was ending the series. This big external change was actually changing me. What better way to express it than to end a 12-year-run, and by saying that life changes and you have to move on. It became bittersweet. All Over Coffee was a dream come true. I got to do exactly what I wanted in a public forum and have the world respond to me, and now it was time to have another dream.

In a way, isn’t that what we all have to do all of the time? We have to take these crappy things that happen to us and we have to decide — are we going to be victims to it, or are we going to grow from it? I know I’m venturing into clichés, but it really is the truth. Are you going to carry stuff around with you? Or are you going figure out the best way to handle it? That’s really what I want the message of the book to be.

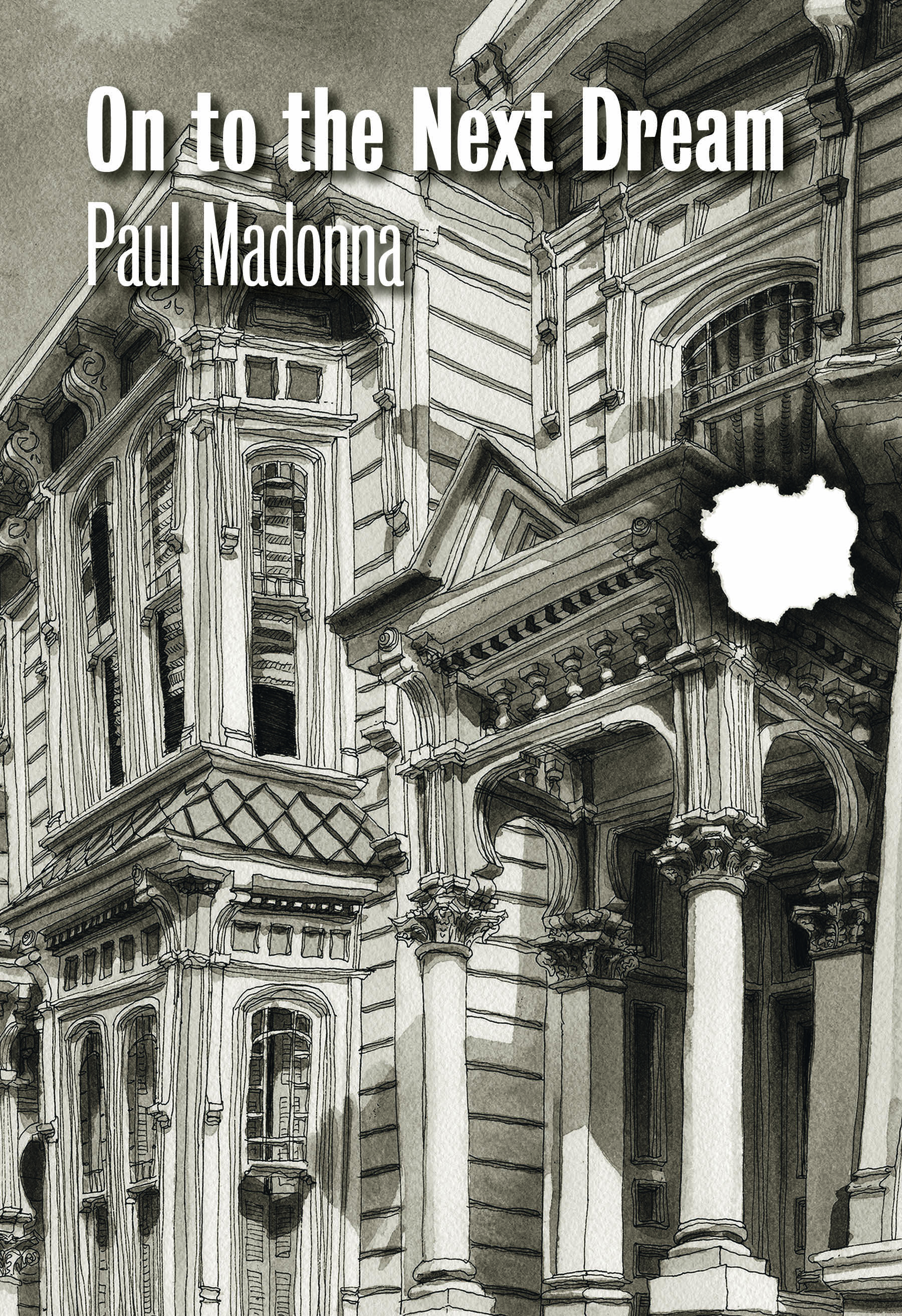

What about the burn marks that run through the book from the cover to the last pages?

When I realized the series was ending, I thought, “I can no longer draw San Francisco the way I used to.” The burns became symbolic of this style of drawing, this love affair, this way of looking at the world that can no longer be the same.

I knew this wasn’t just my story, but the story of every person who ever wanted their version of their world to stay the same. And those are the final words of the book: It was time to let go. Time to move on. On to the next dream.

And the older you get, the more you realize it’s never going to stay the same.

And so we have to change our definitions. We have to change what our version of the world is. These days I feel like life is just a series of disillusionments. We think that the world is getting worse but I actually think the world has always been what it is, we just grow to understand it more.

I love the part where Paul meets Future Paul who tells him what’s going to happen. How much of that is true? How has the story played out?

The events on page 62 are essentially all true. I still live in the city. I live in the Excelsior now. We landed fine. We found a place. It was trying and difficult and expensive and it took a while. And I have to say that the first year felt pretty unsettled. We were still reacting and we had a hard time settling. It’s like once you fall in love again but you’re terrified of getting your heart broken. It’s underneath everything and you don’t realize that’s the heartbeat that is guiding you emotionally.

But, physically we’re fine. We were two healthy people with means and community. It was community that helped us find a place — a fan offered us their home. In that way, I’m not the everyman. Sure, I’m not a big-time celebrity, but the average person who loses their home doesn’t get people reading their story. I had to acknowledge that for myself. Again, that’s why I felt stuck in between both worlds. I wasn’t a big enough celebrity that I could just go buy a home overlooking the ocean, but I wasn’t so common that I got swept out to sea.

I didn’t have to move into a tent, which we see a lot more of. Remember, we lose miles by slipping inches. Because we no longer look at those tents and say: Good lord, why are there four times as many tents as last year? Who are these people? Could some of them be people that I interacted with on a daily basis and I didn’t notice when they disappeared from behind the coffee counter or from the grocery store? We don’t stop to think, “Did they have more?” Again, we assume that it’s their fault. We don’t think those things out loud. We just think they didn’t take care of their lives and that’s why they’re out there. And I think some of that attitude comes because it is difficult to make your way. We all have to do things that are uncomfortable and hard and take sacrifice. And we all want more.

And some of us have more of a safety net than others do.

That’s why I don’t want the book to be about eviction. I don’t feel like I have a right to make any grand statements about it. There are many more people that are actively involved in the problems of eviction, who are helping people whose lives have been severely destroyed and upended. What I’m best at giving is this: I can write and I can draw and I can have the biggest effect possible through this medium. I have two guiding principles right now: beauty and entertainment. There is a lot of difficulty in the world. I want to be able to offer something that’s beautiful, entertaining, and thoughtful.

Paul Madonna appears at City Lights on April 19 at 7pm. For more details, as well as other upcoming book appearances, see here.