There’s an inherent inadequacy to writing about the work of Tosha Stimage — one that inevitably unravels the act of writing about art altogether, or even using language at all.

The Oakland-based multidisciplinary artist makes work that is essentially about the limitations of language, and the ways in which words can actually work to abstract complex concepts — rather than help to explain them — particularly when it comes to talking about race.

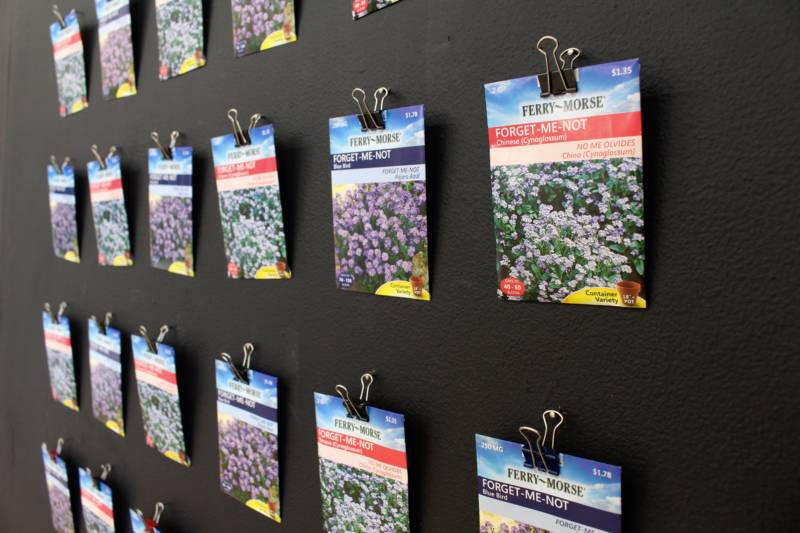

In her first solo show, Death Valley Covered in Flowers at City Limits Gallery, she diligently unpacks and re-presents discourses surrounding death and black identity in a way that preempts common associations with both, and brings forth latent relationships that would otherwise be overlooked. In the process, she manages to make the work about a million other things as well: the history of oranges, the lifecycle of a flower, the symbol of the labyrinth, and Astroturf, for instance.

But like an intricately spun web, all the pieces ultimately fit together to form a coded conversation about race and mortality that avoids familiar tropes. “I’m interested in language and the way that we use these forms that we’ve reinforced meaning into to construct identities which control the way people are able to move or not move through the world,” says Stimage. “How can I use things that aren’t necessarily overtly black to talk about blackness?”

In practice, that’s manifested in a show dominated by circular compositions. The most commanding is a bright orange wall painted to mimic the target sheet from the first time that Stimage shot a gun, complete with bullet holes. To the right is a tapestry featuring the woven close-up image of a black man’s scalp with tight braids forming an elaborate pattern that points to the center of his cranium. On the floor, there’s a labyrinth cut out of Astroturf alongside its own negative image. And above the mazes, a pedestal holding a pile of oranges.

The show’s visual code can feel confusingly esoteric, but in conversation Stimage readily reveals the extensive research and philosophical inquiry that went into each detail and decision. The fact, for instance, that in multiple cultural traditions labyrinths represent a path to finding oneself — but, to Stimage, can also be thought of as a trap representing the dangers of fixed definitions of identity. Or, for instance, that the practice of weaving can be considered a precursor to binary code — a fact that relates to Stimage’s interest in the relationship between technology and language; in particular, how smart phones and social media, like labels, allow us to create shorthand for peoples’ identities.

“I’ve been thinking a lot about death and thinking a lot about these figures who in our society become hashtags and how we compress so much about a person’s whole entire life and existence into this symbol so that we can readily associate ourselves with a movement,” says Stimage. “There’s something really disturbing about it to me.”