“Cassette tape resurgence” — it’s a phrase whose very utterance seems to beg several questions: How? Why? And for whom?

The subject of numerous thinkpieces, hullabaloo, and general derision, the return of the cassette tape seems, at first glance, to be little more than a bad joke about hipsters made manifest in corporeal form. For those old enough to remember when cassette tapes were the de facto standard, there doesn’t seem much to celebrate about their return: cueing a particular track involves a good deal of guesswork and repeated mashing of rewind and fast-forward; their artwork (or “J-card,” in the vernacular of the cassette otaku) is small and mostly insignificant; and worst of all, every cassette tape player seems prone to occasional bouts of cannibalism, eating the very tapes they were designed to play, enacting a vicious blood price for the mere enjoyment of music.

Regardless, after nearly a decade into their return, they don’t seem to be going anywhere. Why, you ask? The answer was succinctly stated by our dynastic philandering former president William Jefferson Clinton a full quarter-century ago: “It’s the econom[ics,] stupid.”

Simply put, cassettes are a boon to artists, offering a cheap and easy way to release music on a physical medium for an increasingly tight-fisted audience. Some facts and figures, courtesy the Nielsen Music Mid-Year Report for 2017:

- Total audio consumption, which Nielsen defines as individual album sales plus TEA, or “track equivalent album” (10 song sales = 1 album sale) and SEA, or “streaming equivalent album” (1,500 streams = 1 album sale) is at 235.5 million units, a +8.9% change over 2016.

- Streaming — that is to say, music consumption which listeners generally do not pay for — is growing at an enormous rate. On-demand audio streams are clocked at 184.3 billion units, a +62.4% change over 2016. Taking both audio and video streams into account, total on-demand streaming is clocked at 284.7 billion units, a +36.4% change over 2016.

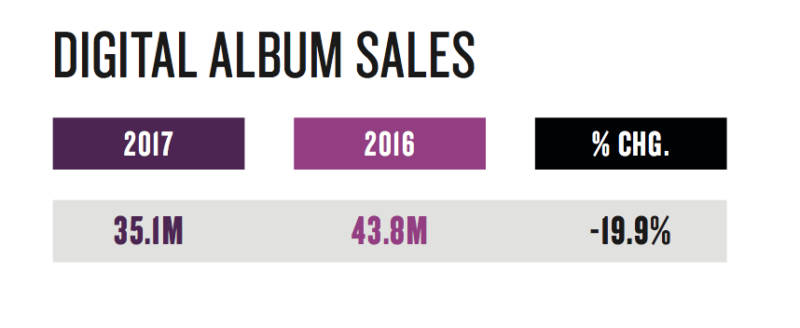

- Meanwhile, album sales are dropping precipitously. Album and TEA sales were clocked at 112.6 million units, a -19.9% change from 2016. Digital album sales clocked at 35.1 million units, also a -19.9% change from 2016; physical album sales clocked at 46.9 million units, a -17.0% change.

To wit: More music is produced, released, and consumed than ever before in history, but fewer and fewer people want to pay for it. And while a new record on vinyl commonly costs between $20–$30 these days, cassettes are still often around the $10-or-under range.

Years ago, I conducted an interview with German electronic musician Uwe Schmidt, best known as Atom Heart or Atom™. Active since the late ’80s, he has released hundreds of records across three decades, and summed up the present-day conundrum: “Today, you either go full commercial or full underground — there’s not really anything in between. In the ’90s and most of the ’00s, until 2008 or so, there was still a middle ground. You could make underground music on an underground label and still sell 5,000 copies, doing something really weird. That doesn’t happen anymore. In the ’90s, it was much easier to to make music and make a living.”