“Well-behaved women rarely make history” goes the old quote, but the truth of the matter is that the contributions of powerful women are too often sidelined in favor of their male counterparts. A perfect example can be found in Dolores Huerta, founder of the first farmworkers’ union in America. You’ve most likely heard of her compatriot Cesar Chavez. You’ve probably heard the chant, “Sí, se puede!” which was actually coined by Huerta.

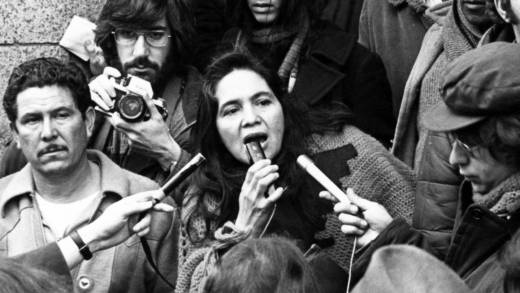

Dolores, a new documentary by writer, producer and director Peter Bratt aims to set the record straight — while Huerta, now 87, can still tell her own story. The film’s tagline says it all: Rebel. Activist. Feminist. Mother. “We want to set the record straight, I mean, women cannot be written out of history,” says one of Huerta’s eleven children. That documentary doesn’t fall short of this goal. I was brought to tears by the end, realizing I’d too long understood Huerta to be a lesser sidekick, almost a secretary, to Chavez.

Chavez’ name can be seen on schools and streets across the United States. And on calendars: In 2014, President Obama declared March 31 Cesar Chavez Day. Huerta, on the other hand, hasn’t received the same recognition. In one infuriating example in the film, an Arizona legislator refers to her as “Cesar Chavez’ girlfriend,” which hits like a slap on the face once you understand the work she did and the sacrifices she made.

After all, Huerta was the co-founder of the United Farm Workers labor union. She negotiated a labor contract between the farmworkers and Schenley Industries wine-grape company, a historical first, and she was a core promoter of the wildly successful national table grape boycott of the late 1960s. After interviewing dozens of politicians, educators, labor historians, ten of Huerta’s eleven children, and Huerta herself, director Peter Bratt became convinced that Huerta was the victim of a “deliberate erasure from historical record.” In effect, this erasure is punishment for living an unconventional life.