The late British dramatist Sarah Kane’s infamous first play Blasted begins under depressingly normal and rather crass circumstances.

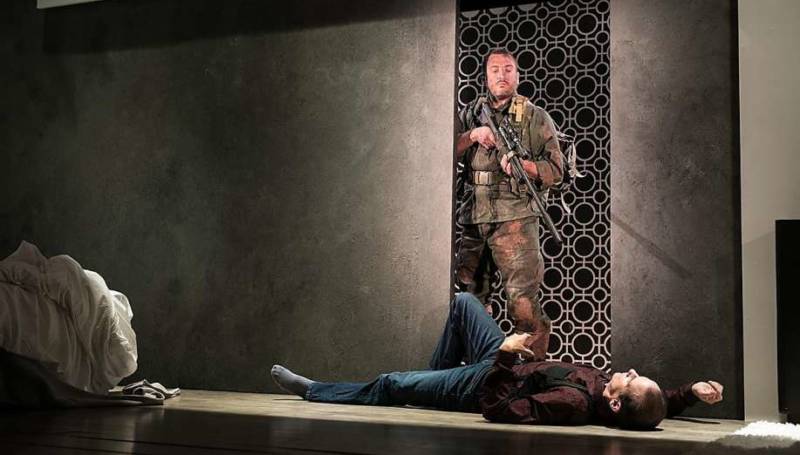

Cate, a young woman, barely out of her teens, and Ian, a seasoned journalist barely in his fifties, enter an upscale hotel room for what looks like a tawdry good time. The pairing of his gun and her backpack might make us pause, but not enough to jar us from what we know of these types of liaisons.

Kane shifts the focus from the mundane to the disconcerting almost immediately, as both Ian and Cate’s bodies appear to be in a state of permanent failure. He’s caught in some nether zone between coughing and vomiting, and her outbursts of stuttering feel closer to seizures than a speech defect. That she also occasionally falls into a narcoleptic trance is both terrifying — anything might happen while she’s unconscious — and a welcome respite for a mind in constant and overwhelming despair.

How these two people negotiate and what they expect from this brief encounter is caught in a tangle of memories — not only of their past (which as you might guess is fraught), but also the fragments of our cultural past as well. Kane fills the stage with signs of what romance once was, even in its most illicit incarnations. There is champagne, a shower, room service meals, and of course the bed. But the most potent and simplest image is a bouquet of flowers.

They are a constant reminder of where we — and they — need to return, a kind of path to the resurrection of normal relations. Watch the way Robert Parsons as Ian in Shotgun Players’ brilliant production manipulates this simple image and you’ll get a sense of why so many writers, directors, and actors are entranced with Blasted and Kane’s subsequent work. Each transformation of the bouquet is a masterpiece of dramatic concision, as you never quite know what’s going to become of those flowers.