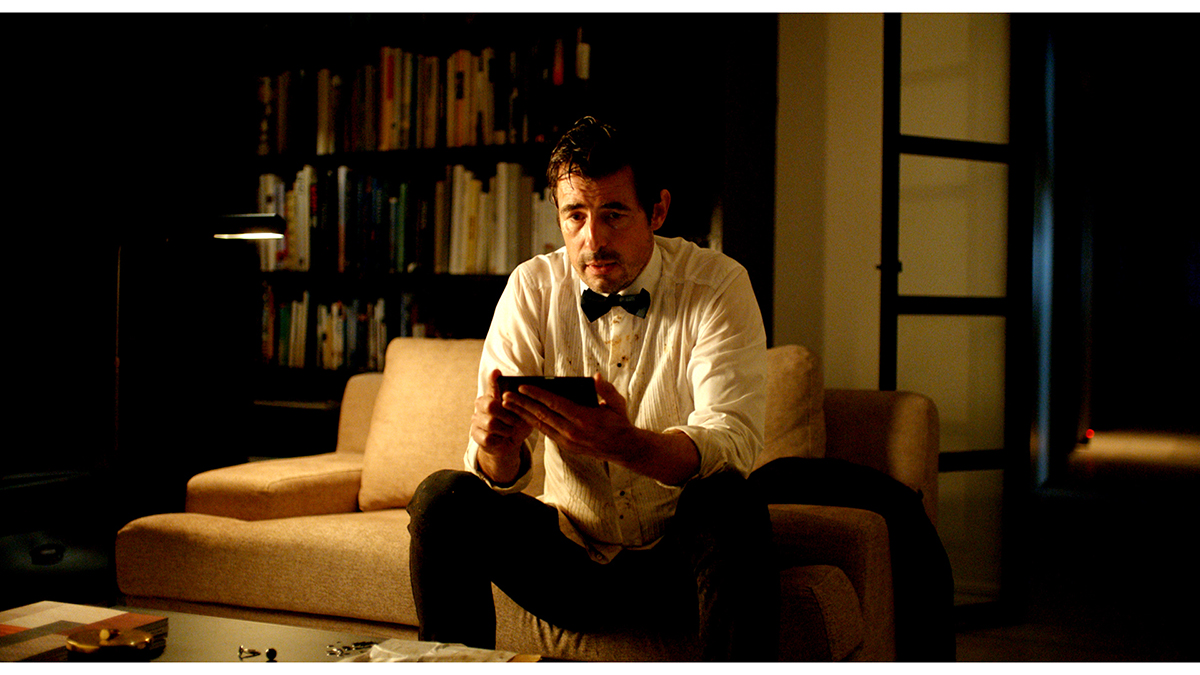

The off-center opening shot of Ruben Östlund’s film The Square focuses on a man who’s asleep on the job. Christian (Claes Bang), the chief curator of a contemporary art museum in Stockholm, is sprawled on the sofa in his office when an assistant enters the room to wake him. He’s due to meet a reporter in one of the galleries.

The Swedish director frames the press interview that follows with a neon installation reading “YOU HAVE NOTHING” directly above Christian’s head. The sign is both the measure of Christian’s spiritual capital and Östlund’s opening announcement; over the next 150 minutes, The Square will expose this character’s moral bankruptcy to the audience.

From the outset, Christian, a lanky 6-foot-4 libertine, appears to be equal parts arrogance and absent-mindedness. Not a sinister man, certainly, but one with several recognizable flaws. But what makes this particular character so deserving of a comeuppance?

In a recent phone interview, Östlund discussed what interested him most in taking Christian to task. He explained that he “was looking at him from the power position that he has, as a privileged man, and the kind of pressure that you are under when you are in that position.” As the character makes a series of bad decisions, Östlund wanted to see how he’d react to losing that privilege.

Outside of his workplace obligations, Christian is a divorced father with two young daughters. These girls would be marked for tragedy in the hands of other Nordic filmmakers like Ingmar Bergman, Thomas Vinterberg and Lars von Trier — yet while Östlund’s vision is at times severe, it is not overwhelmed by gloom.

He pitches absurdity and wit against depression, citing Roy Andersson (A Pigeon Sat on a Branch Reflecting on Existence) as an influence over Bergman. But he does admit that the Dogme 95 movement, started by Vinterberg and von Trier, was “a very, very great inspiration because they used the energy of the low-budget movie in a creative way. I was in film school when they started to make movies. ”

‘The Square’ opens Friday, Nov. 10 in San Francisco at Embarcadero Center Cinema and the Alamo Drafthouse New Mission Theater. For more information,

‘The Square’ opens Friday, Nov. 10 in San Francisco at Embarcadero Center Cinema and the Alamo Drafthouse New Mission Theater. For more information,