One of Shakespeare’s least-produced plays, Timon of Athens has several strikes against its popularity. Possibly unfinished, the play is thought to have been partially written by prolific Jacobean playwright Thomas Middleton, and doesn’t appear to have ever been performed during Shakespeare’s time. Its also difficult to categorize: Timon is sometimes labeled a tragedy, sometimes a “problem play,” and rarely ever someone’s “favorite.”

Even so, it’s been on the shortlist for Cutting Ball Theater’s co-founder Rob Melrose since 2000, when the then-fledgling company was tapped to stage a reading of the work for the Bay Area Shakespeare Marathon, and it was a surprise hit.

Now, on the verge of Cutting Ball’s 20-year anniversary, Melrose’s adaptation of Timon of Athens is both a testament to the experimental nature of his brainchild company (slated to turn over to associate artistic director Ariel Craft in July), and a reflection of the economic disparities that characterize his adoptive neighborhood, the Tenderloin, where Cutting Ball resides at EXIT on Taylor.

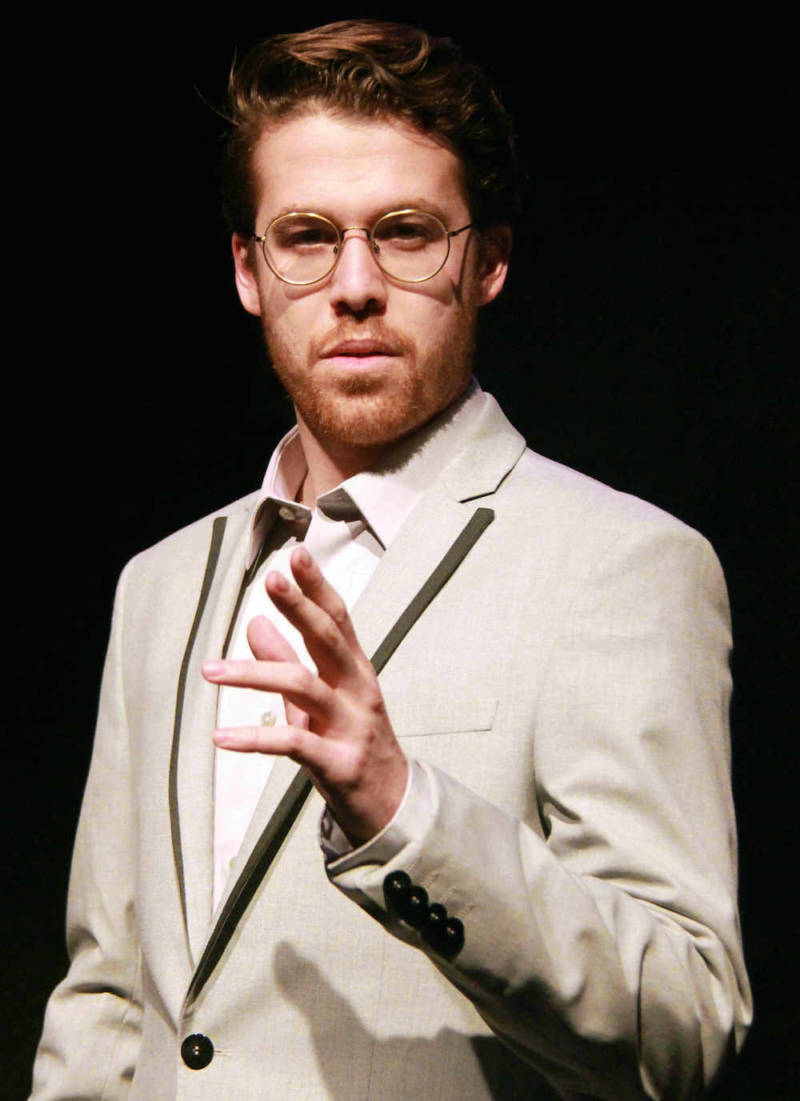

When we first meet Timon (Brennan Pickman-Thoon) he’s jovial, benevolent. He pays out gold to cover a friend’s debt, increases the status of a manservant that he might wed, then invites everyone over for a feast at his expense. Clad in neat, inoffensive grayscale and expensive sneakers, he’s the very model of a modern-day, tech-minted millionaire. The citizens of Athens, all too happy to avail themselves of his seemingly bottomless generosity, carouse with him and sing his praises — all except the ragged philosopher of the street, Apemantus (David Sinaiko), whose ill-tempered pronouncements offer ignored foreshadowing of Timon’s eventual downfall.

While Timon as careless spendthrift is as colorless as his tailored suit, Apemantus as oracle is vulgar, florid, and dynamic, cursed like Cassandra to be disbelieved as he looks into the hearts of Timon’s inner circle and finds them hollow. “Who lives that’s not depraved or depraves?” he demands, as a cupid in silver disco chaps (John Steele Jr.) gyrates across the platform thrust of the stage (designed by Michael Locher) as if on a catwalk. Melrose deftly transplants this ancient bacchanal to the decadent excesses of the Bay Area elite, complete with wedge-heeled dancing girls, Venetian party masks, and a blowhard in a custom leather vest (Douglas Nolan, as Ventidius), who busts out an opportune baggie of cocaine, aka “four milk-white horses, trapped in silver.”

It isn’t until Timon’s swift fall from favor once his money runs out that the play really comes into its own. Described by Shakespearean scholar G. Wilson Knight as a “pilgrimage of hate,” Timon’s descent into poverty and justifiable indignation of his so-called friends’ refusal to help in his time of need rivals Lear’s downward spiral. In his “cave” crafted of blue tarp, his clothing reduced to rags, talking frequently to himself, he cuts an all-too familiar figure of urban impoverishment. In just a few scenes he’s gone from one extreme to the other, a fact that Apemantus remarks upon when he comes to visit and trade comically caustic insults.