We are in a cultural moment where men’s predatory behavior — in the workplace, at parties, in living rooms and in the White House — has wrung dry any grace that dictums like “boys will be boys” previously provided. Critics sportingly hunt down that dictum wherever it appears, and one only wishes it a rapid extinction.

Personally, I hunger for more complicated views of masculinity. I couldn’t stop talking about Moonlight after I saw it. I remember curling up with my blanket and emotions on an airplane, landing and renting it again as soon as I returned to my apartment. I paused only to appreciate the beauty of its tonal blues and tenderness; its achingly beautiful and wholly unpredictable grace.

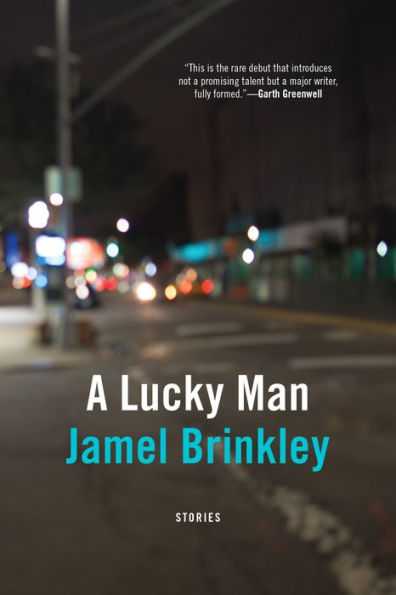

A Lucky Man, out this May, is the stunning debut short story collection by Jamel Brinkley, one that reminds me of Moonlight. It is not a book about gay men, though. Rather, Brinkley explores black men under both the pressurized violence and bottled up tenderness that undoes them at every turn. This is a book that acknowledges male stereotypes while subverting them and exploring the psychic damage they leave in their wake.

Brinkley builds his stories over the lowly clatter of life: recent college graduates on the prowl for girls; teenage boys on the prowl for a glance up a skirt; small boys on the prowl for haircuts that will make them look like men; and grown men on the prowl for something, anything, that will make them feel more whole.