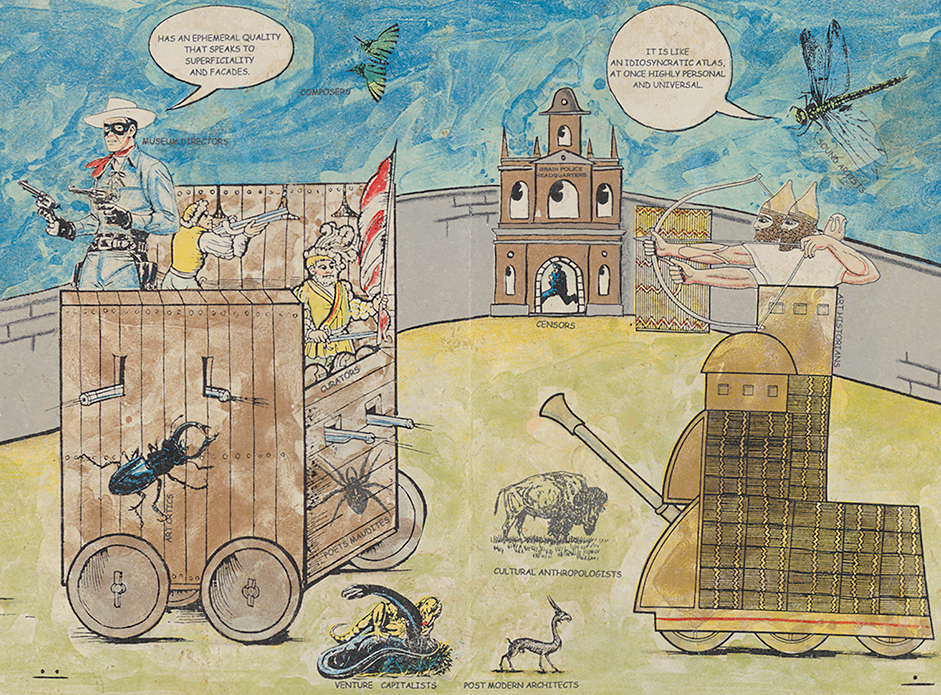

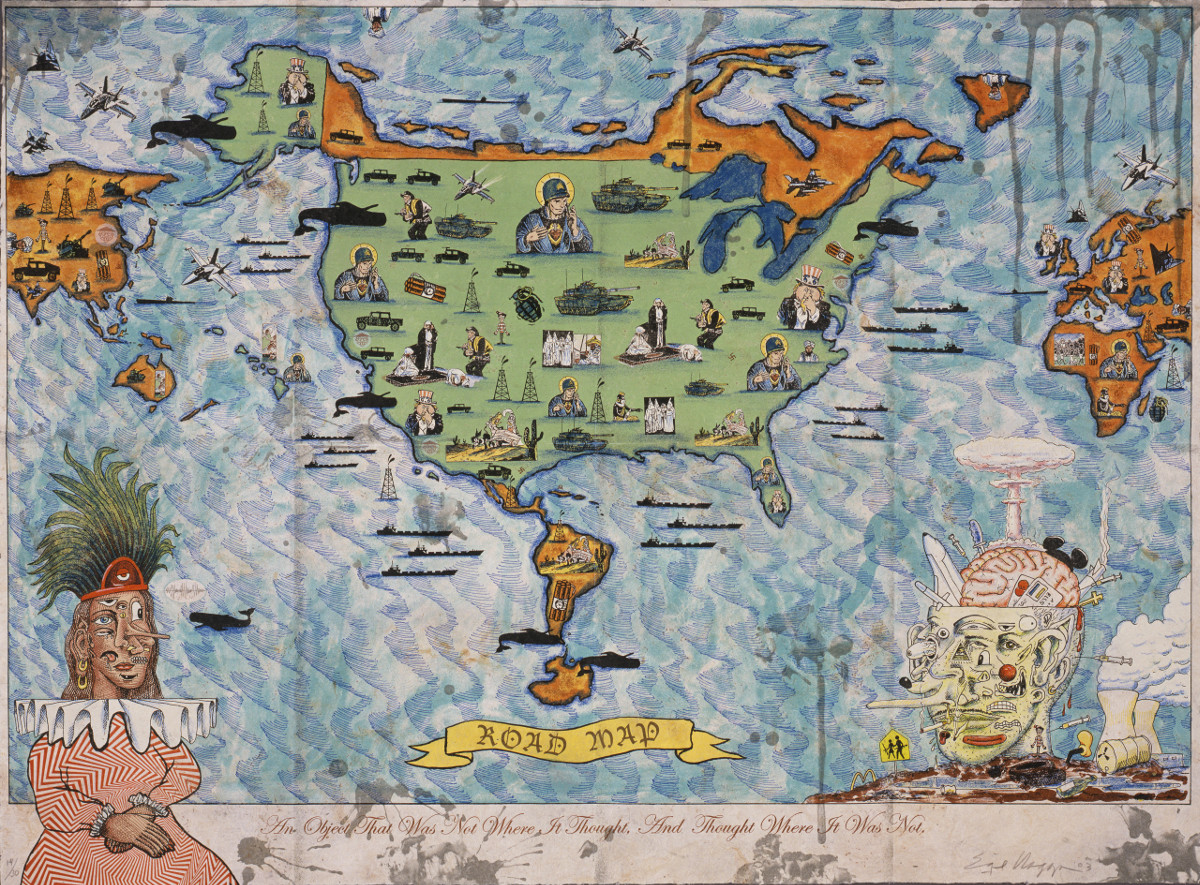

It’s difficult to write about Enrique Chagoya’s art. Much of the San Francisco–based artist’s work is seemingly narrative, and Chagoya’s rich imagery and text provide numerous jumping-off points. But these narratives aren’t always linear (even when presented in the form of seven-foot-long manuscripts), avoiding obvious beginnings, ends and sometimes even consistent internal logic. Meaning is particularly elusive in the body of work on view at Reno’s Nevada Museum of Art in Enrique Chagoya: Reimagining the New World.

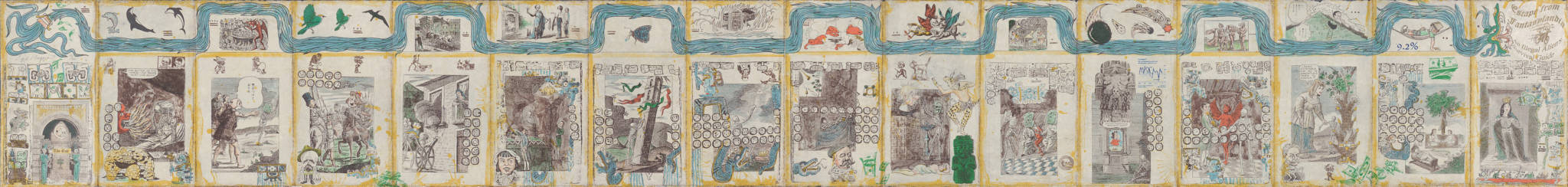

A hallmark of the exhibition is a wild pastiche of iconographies, languages and cultural signifiers. Chagoya’s Escape from Fantasylandia: An Illegal Alien’s Survival Guide, a 16-panel print that resembles Aztec and Maya codices, epitomizes this approach. Mesoamerican motifs are present throughout, and an 80-inch rendition of the god Quetzalcoatl runs the length of the print. Intricate illustrations populate the panels: skeletons, the devil, serpents, Fantastic Four’s The Thing, Astro Boy and a tertiary character from the Saturday Evening Post comic Little Lulu.

Full comprehension of the constituent stories in the codex doesn’t appear to be Chagoya’s goal. The text in Escape from Fantasylandia, for example, appears intermittently in Spanish, Japanese and English. And while many people can read all three languages, that’s a narrower viewership than the artist likely intends.

Likewise, in much of Chagoya’s work references from popular culture are instantly recognizable, but equally prevalent are the difficult-to-identify characters. These images are more powerful for the broader cultural associations they elicit, instead of simply referencing the specific media from which they originated. Little Lulu represents 1930s and 1940s Americana, and American pop culture in general, even for the art critic who needs to conduct research just to determine the comic’s origin.

Non-Indigenous artists often appropriate Indigenous imagery in such a way that the artists detach signifiers from their historical contexts, erase their meaning and use the appropriated material as exotic adornment. In Escape from Fantasylandia, Chagoya reverses this process by freeing American and Japanese signifiers from their meaning and incorporating them in a text created from and for an Indigenous or Mexican perspective. For those accustomed to their culture’s international dominance, it can be disorienting to construct meaning from familiar imagery cleaved from its significance.