Nothing succeeds in Hollywood like success. So box office champs Jordan Peele (Get Out), Ryan Coogler (Black Panther) and Ava DuVernay (A Wrinkle in Time), best picture director Barry Jenkins (Moonlight) and Oscar nominee Dee Rees (Mudbound) now have the clout to continue making movies about black people (and anyone else they like). With luck and positive word of mouth, the Oakland-set indie features Sorry to Bother You (now in theaters) and Blindspotting (opening July 20), will click with audiences and launch their creators’ careers.

This isn’t the first time a wave of black filmmakers galvanized American movies. Black Powers: Reframing Hollywood (July 12-29), the sixth edition of SFMOMA and SFFILM’s insightful dialogue between older and contemporary films, isn’t inspired by a single filmmaker (like previous Modern Cinema series centered on Claire Denis, Johnnie To and Todd Haynes) but by an infiltration process: the ebb and flow of black filmmakers past and around the studio greenlighters who serve as de facto gatekeepers.

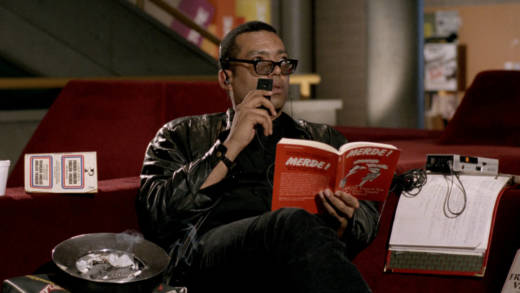

The first weekend of the three-part series boasts an array of landmark films, from the peerless writer-director Oscar Micheaux’s 1925 silent Body and Soul to Charles Burnett’s 1978 low-key working-class character drama Killer of Sheep to writer-director-actor Wendell B. Harris’ 1989 fact-based impostor fable Chameleon Street. Spike Lee’s career-making Do the Right Thing (a summer 1989 sensation) rounds out the lineup with Jenkins’ delectable S.F.-set 2008 debut Medicine for Melancholy and last year’s Get Out.

The other two weekends are given over to films that clamor to be re-watched (or discovered) post-Ferguson and post-Black Panther, augmented with an array of guests (check the lineup). The private-eye movies Shaft (directed by Gordon Parks) and Carl Franklin’s Devil in a Blue Dress (the first in what should have been a franchise based on Walter Mosley’s series of Easy Rawlins novels) shouldn’t be underestimated as pulp entertainment.

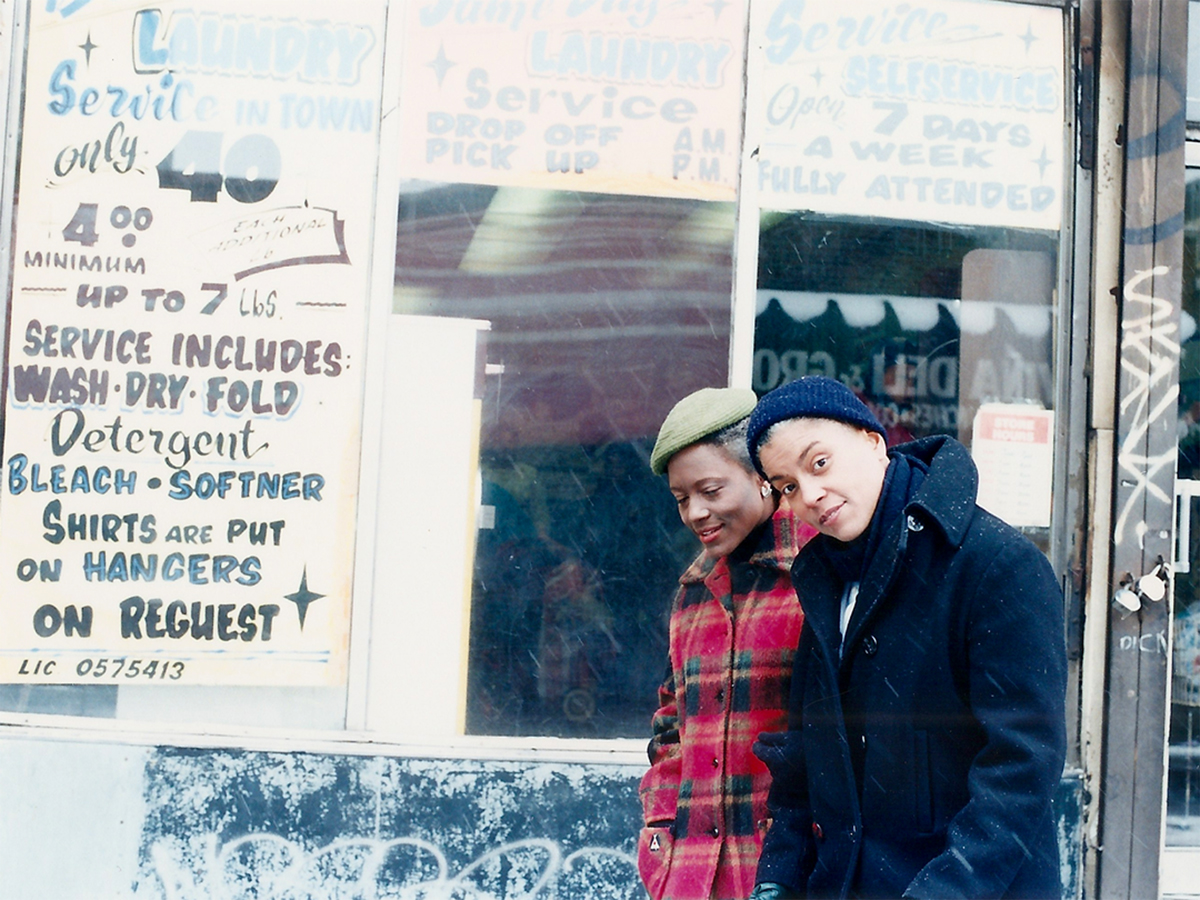

Godfrey Cambridge, an unjustly forgotten comedian and actor, is a brassy pleasure in Watermelon Man and Cotton Comes to Harlem. Cheryl Dunye’s 1996 queer classic, The Watermelon Woman, connects eras in African-American life and cinema, while Pariah, the 2011 feature debut by Dee Rees, tells an unflinching, sexually charged coming-of-age story.