If everything goes as planned, the rosy piece of alabaster currently propped up on wooden pegs at the Headlands Center for the Arts will have a nice big hole in its middle by 2064.

Gala Porras-Kim, the artist who placed it there, will be 80 that year, and she’s looking forward to seeing the hole. She’s creating it herself, positioning a water drip just above the soft rock’s center that releases one small drop about every three minutes, just when the previous drop has dried.

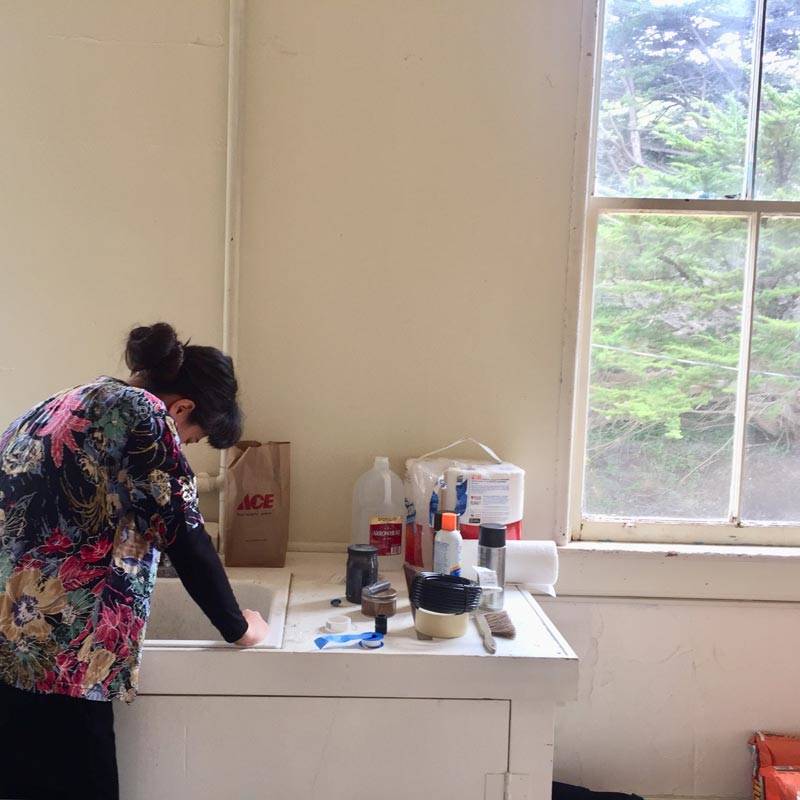

Now age 34, Porras-Kim is experimenting for the long term during a Headlands residency that she’s titled Trials in Ancient Technologies, which culminates in a reception for the public this Sunday, July 15. In addition to the alabaster time clock (officially named Untitled (Water Erosion)), four other pieces have resulted from her tenure in the Headlands’ Project Space, a time she says has been a welcome respite from her rigorous studio practice at home in Los Angeles.

Born in Colombia in 1984, Porras-Kim has an MFA from the California Institute of the Arts and an MA from UCLA. An emerging artist whose career is off with a bullet, her work has been shown at the Whitney, LACMA, and Hammer Museum and she has won a growing list of awards and grants. Interested in the lives of indigenous peoples—those of Mexico in particular—as well as the concepts of canonization, erasure, and appropriation, Porras-Kim’s work is cerebral to the extreme. Her objects, drawings, and relational constructs consider how to carve pathways of understanding towards long-gone peoples that perhaps exceed the ability of mere language to parse.

In the past, she has curated the unidentified potsherds and fabric scraps that institutions regularly store. Recently, she worked with the archives at UCLA’s Fowler Museum in an attempt to trace something of the lives of the anonymous artisans who made the vessels and the citizens who used them. By usurping conservators, she questioned the right of a museum to own such detritus in the first place, the canonization of some objects above others, and the value of loss.