It’s not every day a museum takes a proud and purposeful stance against collecting artwork. But in September 1968, representatives from the brand-new Studio Museum in Harlem, a space dedicated to supporting black artists and educating the surrounding community about contemporary art, did just that.

“When you have the vested interest of a collection you lose the desire to innovate,” Eleanor Holmes Norton, then-vice-president of the Studio Museum (and current congresswoman for the District of Columbia), told the New York Times. “We’re trying to do something other museums aren’t.”

While the Studio Museum succeeded in fulfilling half of that statement (doing something other museums don’t), it utterly failed to remain a non-collecting institution. Within its first two years of existence, enthusiastic young artists started gifting their own work. And by 1977, a collections committee began accessioning pieces in earnest. Today, five decades after its founding, the Studio Museum houses over 2,500 artworks by approximately 700 artists—a collection spanning over 200 years.

Which brings us to the present day, and the second and third floors of San Francisco’s Museum of the African Diaspora. The Studio Museum is currently constructing a new building for itself in Harlem, and has taken the opportunity to travel its impressive collection around the country in the form of Black Refractions: Highlights from the Studio Museum in Harlem. Its first stop is at MoAD, where the exhibition runs through April 14.

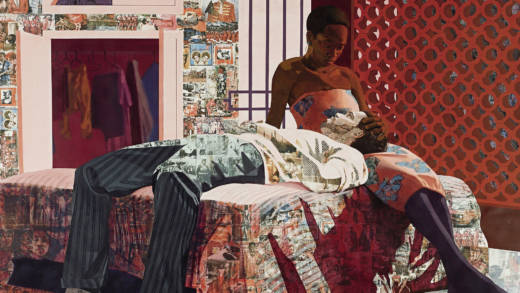

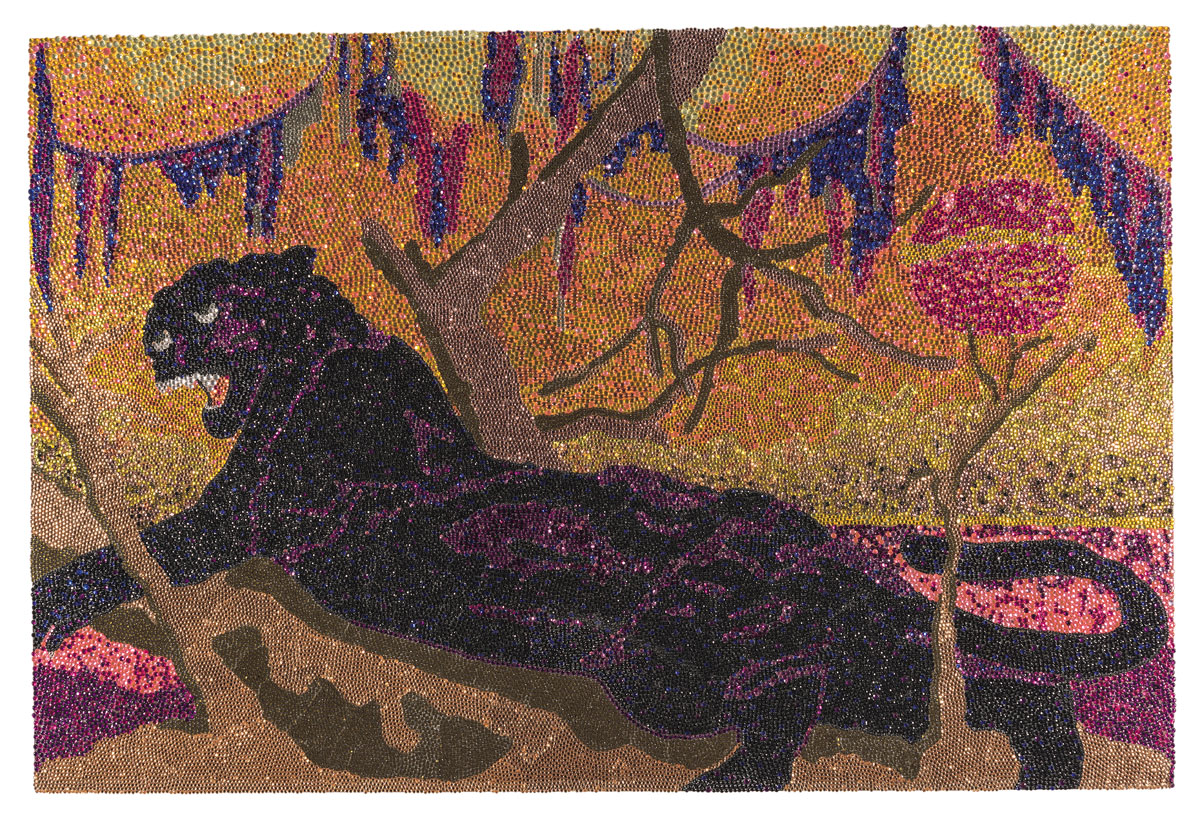

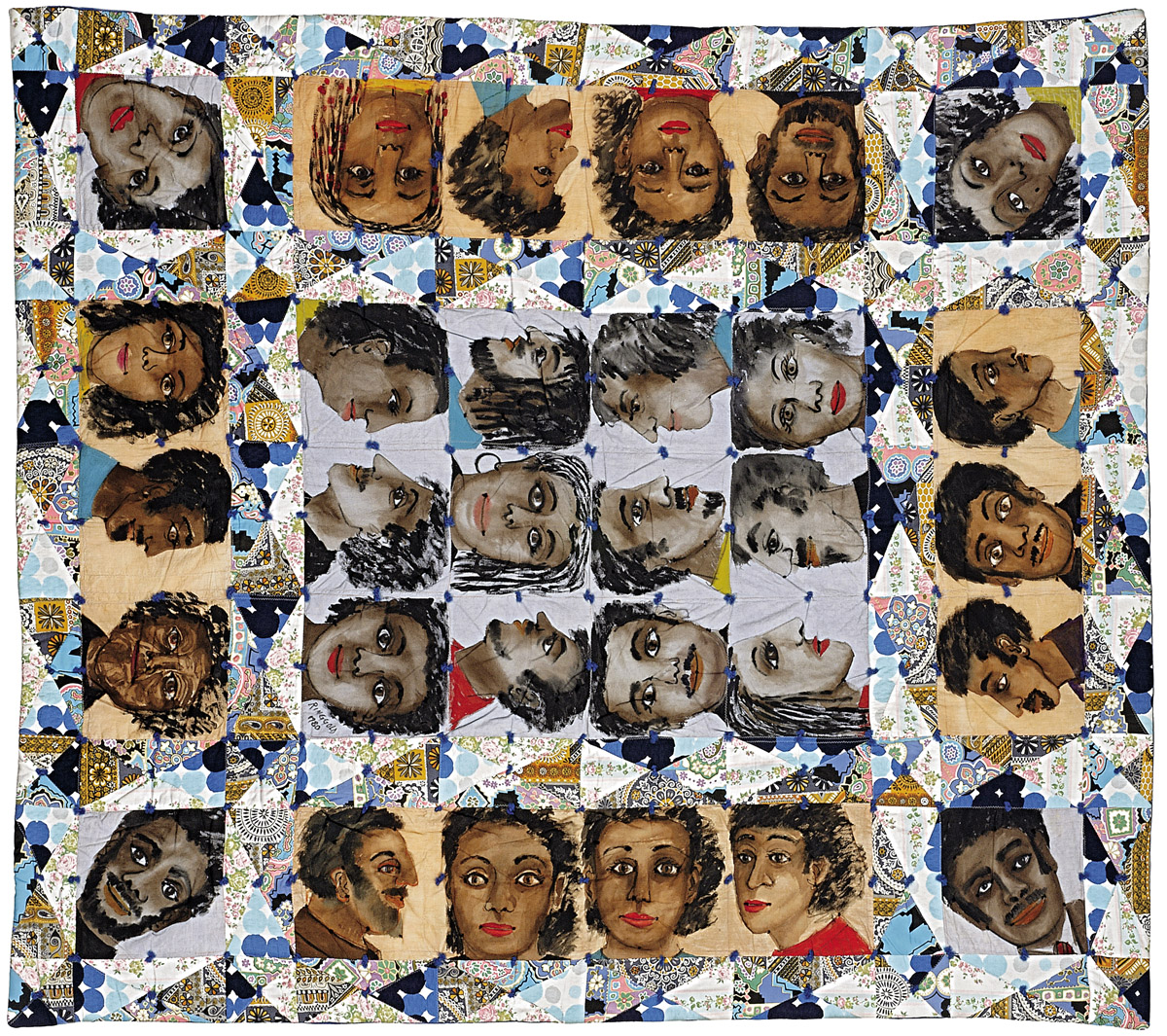

It’s an exciting show for a number of reasons, not least of which is seeing incredible work by contemporary artists of African descent in a local institution devoted to, as a Studio Museum rep says, “proactive and radical cultural specificity.” There’s a who’s-who quality to the Studio Museum’s holdings; among the artists included in the MoAD exhibition are Njideka Akunyili Crosby, Mark Bradford, David Hammons, Glenn Ligon, Kerry James Marshall, Chris Ofili, Mickalene Thomas, Carrie Mae Weems and Kehinde Wiley.