On Monday, Feb. 18, Conrad Meyers addressed roughly 40 supporters of Aggregate Space Gallery convened for dinner in the workshop adjacent to the nonprofit, artist-run space in Oakland. He wore paint-splattered jeans and a leather jacket, and apologized for the chill.

Conrad and his partner Willis Meyers built out the warehouse themselves and opened Aggregate in 2011, offering conceptual and video artists a sharp curatorial eye and malleable exhibition space. Now they’re in the awkward position of doing better than ever, yet also facing an existential threat.

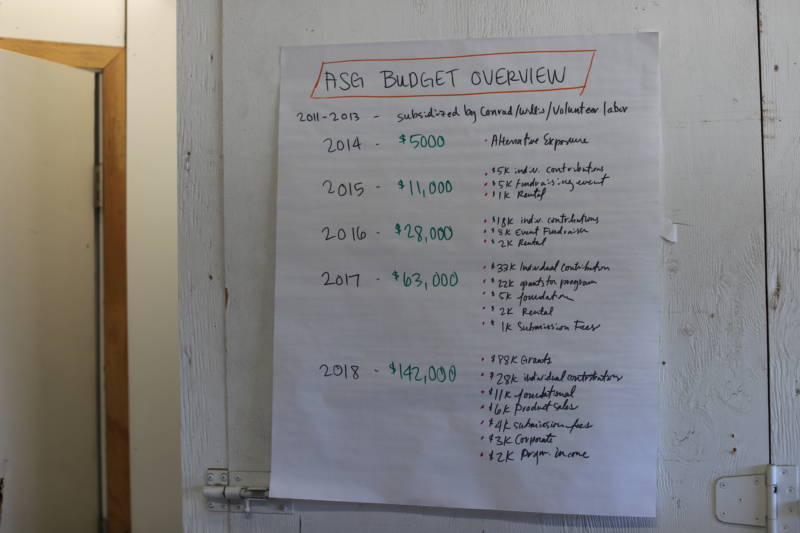

“So, our budget just ballooned by $100,000 from national funders who want us to stay in Oakland,” Meyers said, prompting applause. “But, the thing is, we’re still getting priced out.”

The purpose of the invite-only supper, attended largely by artists and nonprofit professionals, was to turn an ending into a beginning. After two years of negotiations, Meyers said, the landlord is insisting on a $1,500 rent increase and for the tenants to absorb the cost of an estimated $50,000 in code-compliance work. So the Meyers anticipate leaving by the beginning of August, and they’re looking for somewhere to land.

Meyers wanted recommendations on temporary space for satellite programming—noting that, in the working timeline, one National Endowment for the Arts-supported Aggregate show doesn’t have a gallery—and to spread word of a wider search, perhaps with nonprofit partners, for property to buy. Meyers, a fabricator and project manager by trade, said his body can withstand one more from-scratch warehouse buildout.