Which is worse? To have your work minimized as boring and routine? Or trumpeted to the heavens but the credit hogged by the man you work for? These narratives are sadly common when you look at the history of women in science — but they make for good theater, as in the play Silent Sky in San Jose.

The play focuses on a woman named Henrietta Swan Leavitt, whose work laid the ground for later revelations, like the idea the universe is much bigger than our little solar system.

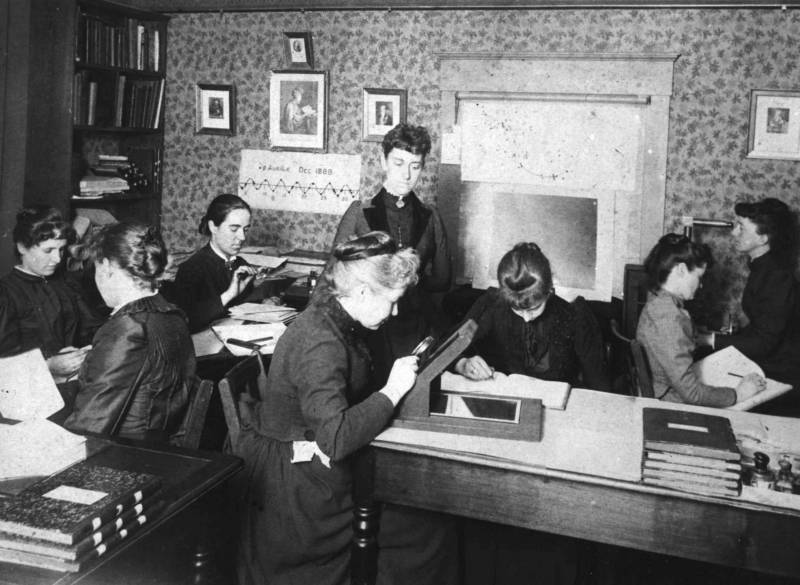

When the Harvard Observatory hired her at the turn of the 20th century, women weren’t allowed to look through its telescopes. The delicate dears might catch a chill in the evening air. Also, they could be paid a whole lot less than men.

Leavitt and other “computers,” as female mathematicians were called then, volunteered or worked for 30 cents an hour cataloguing the brightness of stars on photographic plates taken by astronomer Edward Charles Pickering. But Leavitt, looking down at those plates of Cepheid variable stars, had an a-ha moment. Well, two of them, really.

The brightness of these “variable” stars varies, from day to day or week to week. Leavitt figured out that the longer a star took to change brightness, the brighter it actually was. So, if a star took a longer time to change brightness than others but didn’t appear brighter, it must be farther away.

Looking at a clutch of these stars in the same astronomic neighborhood, the Magellanic Clouds, she came to another conclusion: if one star looked much brighter than another, it was probably brighter. Together, these observations help astronomers figure out relative distances between stars and the Earth.