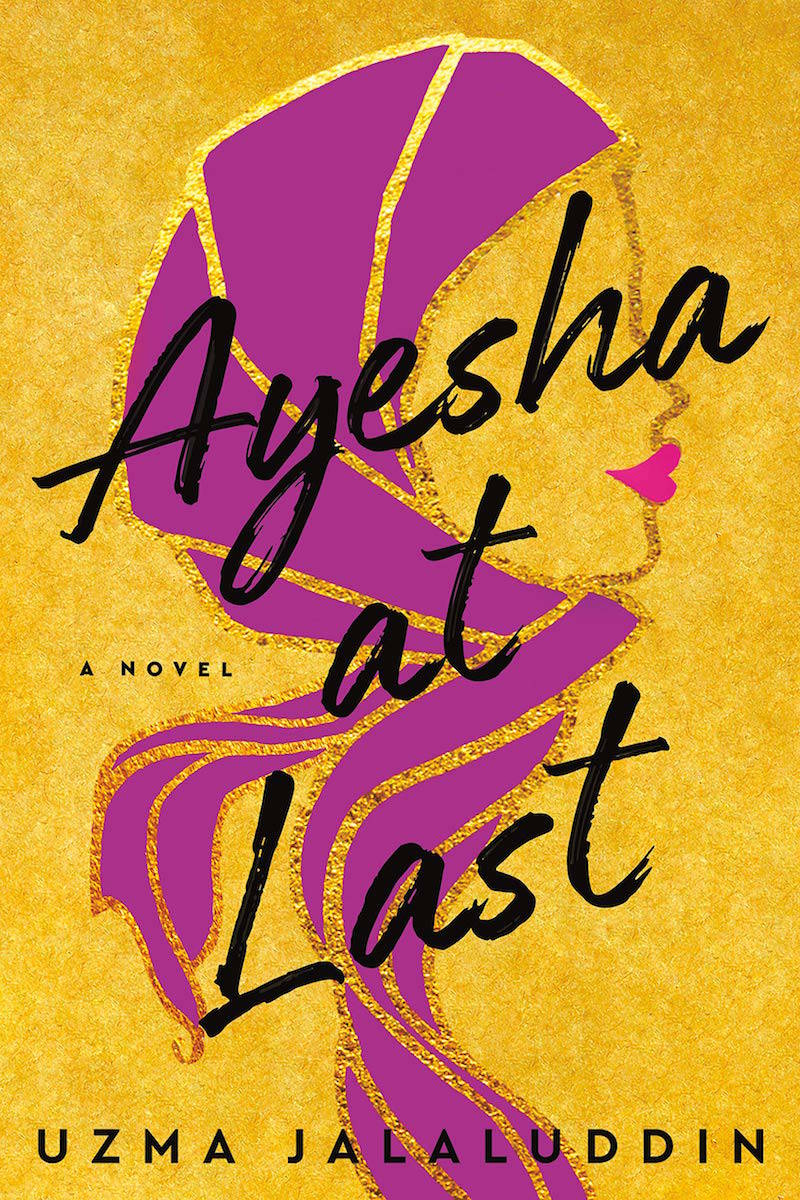

South Asian adaptations of Jane Austen’s timeless Pride and Prejudice have become quite popular recently — and no, watching the 2005 Bollywood-style token film Bride and Prejudice — the only famous Indian adaptation of Austen’s novel — doesn’t mean we’ve seen it all. Uzma Jalaluddin’s debut novel Ayesha at Last — which reads like an Indian soap opera with a dash of Shakespeare — stands out beautifully in the crowd.

The novel kicks off with Khalid Mirza and Ayesha Shamsi, two Muslims living in Toronto, who clash at every turn over different interpretations of their faith. Khalid, who’s more conservative, is content with allowing his controlling mother to run his life and arrange his marriage because “love comes after marriage.” Ayesha, on the other hand, is a fiercely independent poet on the rise, who would much rather focus on her career and find a husband on her own than be pressured into a relationship by her gossipy community, just because she’s getting older.

When they’re forced to work on a conference together at their mosque, judgmental glares and biting remarks give way to a burgeoning attraction that leaves Khalid confused; after all, his mother has always warned him about the dangers of pre-marital love. “These Western ideas of romantic love are utter nonsense. Just look at the American divorce rate,” his Ammi says.