When Ruth Bader Ginsberg attended Harvard Law School in 1956, she and the eight other women in attendance were asked by the dean to justify why they were taking places in class away from men. The women were refused entry to the law school dormitories, the Lamont library and even the Harvard Law Review banquet. So just imagine the indignities that must have befallen Clara Shortridge Foltz, who became the West Coast’s first female lawyer in 1878.

The West’s First ‘Lady Lawyer’ Opened Doors for Women in Law

“Genius, talent and hard labor know no sex,” Foltz once said, sharing a life-long mantra that enabled her to achieve a mind-blowing number of firsts. In her lifetime, she spearheaded legislation to allow women to become law school students, notaries public and administrators of estates. In 1890, she led a campaign for nationwide public defenders’ offices—over two decades before California got its first. In 1910, Foltz became America’s first female deputy district attorney. In 1930, at the age of 81, she was the first woman to run for governor of California.

So where did this tireless innovator come from? Foltz spent her childhood and early teens in Illinois and Iowa, but found herself in San Jose after eloping at the age of 15 with a Union soldier named Jeremiah Foltz.

Raised with a reverence for the law by her attorney father, Elias, Foltz often overheard him telling her mother: “I’m sorry that girl was not born a boy, for then she would have become a great lawyer.” Only after Foltz’s husband left her for another woman, abandoning her with five children under the age of 11, would she conjure the chutzpah to try.

It was then, in 1876, at the age of 29, that Foltz finally began to take steps towards a law career, arguing to all who would listen that moving into a male profession was the only means she had to support her family and keep her children together. Though she divorced Jeremiah in 1879, the story she told the world was that he died suddenly. Disguising her career ambitions as something purely spurred by the love of her children, she was able to earn the sympathy of enough men in the legal profession to advance into it herself.

Though there were 50 other female lawyers in the United States at the time, California’s Code of Civil Procedure prohibited women from joining the profession, expressly stating that only a “white male citizen” could apply to the bar. But with the help of several male allies, suffragist campaigners, a supportive local press and her mother’s assistance with child care, Foltz successfully lobbied for a new bill, the Woman Lawyer’s Act, that allowed women to take the bar.

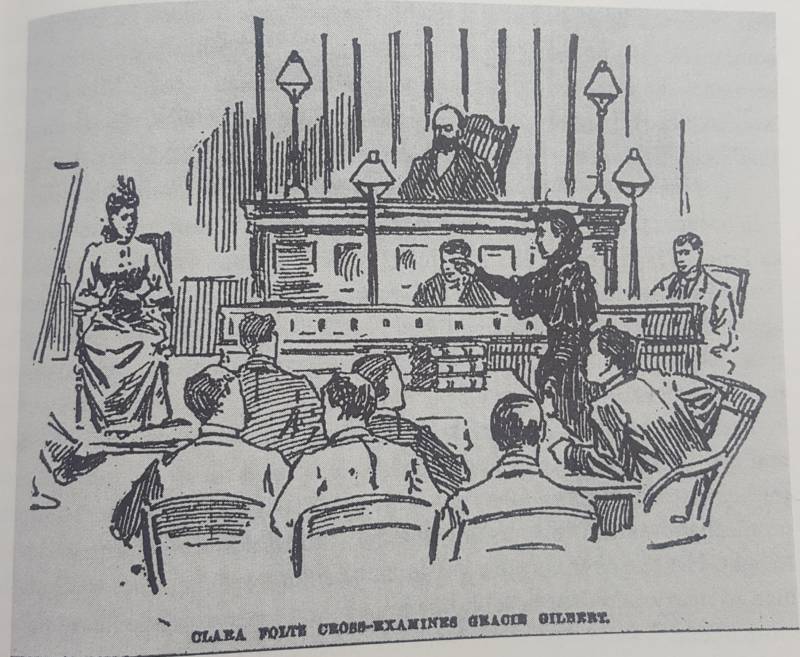

Thanks to Foltz’s commitment to her studies, legal training from her father and his partner C.C. Stephens and a local legal club where aspiring attorneys practiced arguing cases, Foltz passed the bar in 1878, just four months after the Woman Lawyer’s Act was passed. She began practicing in San Francisco.

Though Foltz described this victory as “bliss,” it only spurred her determination to make life better for women all over the world. She traveled the United States and Europe, campaigning for women’s suffrage, and used her position as editor and publisher of the San Diego Bee and The New American Woman to advance the suffragist agenda. In one public lecture, she put her position in no uncertain terms:

“Woman must be either man’s equal or his slave. There is no middle ground. The flag of our Union floats not over one free woman in all this broad land. Every inch gained by her in the last half century has been contested and every inch gained has only subjected her to fresh demands.”

Along with her career and activism, San Francisco proved to be Foltz’s other great love. When moving to New York in October 1895, she confessed to the San Francisco Examiner: “For a long time I have had my eye on [New York] as a larger field, and only my pleasant business and social associations in San Francisco have prevented an earlier removal.”

After finally moving east, initially because she wanted to earn more money and eventually open a women’s law school in San Francisco, Foltz lasted only four years in New York before coming back. Her later move to Los Angeles is said to have been prompted by the 1906 earthquake. She left an indelible mark on the southern part of the state too—today, the county courthouse in downtown Los Angeles is named after her.

Through her barrier-busting life, Foltz found that combining an inner toughness with an outer femininity was the best way to get things done. “They call me a lady lawyer, a pretty sobriquet,” she once said. “For of course to be worthy of so dainty a title, I was bound to maintain a dainty manner as I browbeat my way through the marshes of ignorance and prejudice.”

Foltz died of heart failure on Sept. 2, 1934, at the age of 85. She was at home in Los Angeles at the time. Though all of her impressive achievements stand as testament to her extraordinariness, a quote from her in the April 1916 edition of The New American Woman best sums up her life. “For as I look back over the hard journey,” she said, “and recall the difficulties which seemed insurmountable, and the obstacles that would have awed the heart of the stoutest man, I am amazed at my own temerity!”

For stories on other Rebel Girls from Bay Area History, click here.