There is occasional confusion about the nature of the United States poet laureateship: The selection of laureate has nothing to do with the president.

The poet is selected by the Librarian of Congress, meaning the laureate works for a completely different branch of the government. This is a smart and useful separation of powers: An advocate of free speech and education should not be beholden to a president, especially this one.

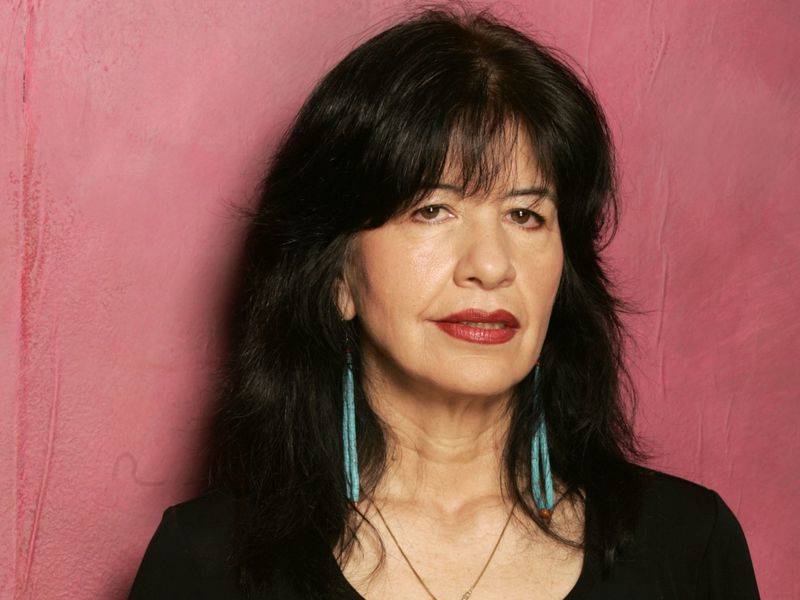

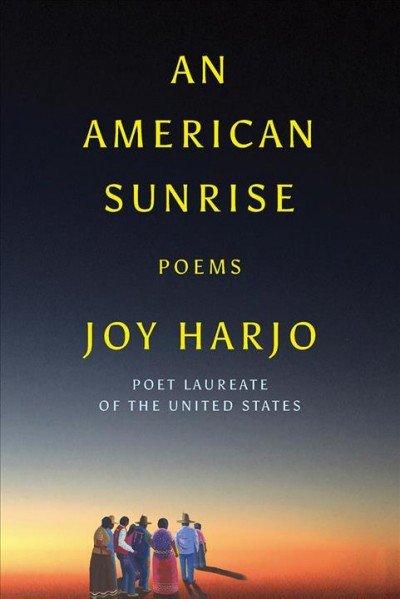

While I do not believe that Joy Harjo’s recent appointment to the laureateship was intended as an explicit rebuke to President Trump, the poetry in her new book, An American Sunrise, casts an undeniably critical eye on the kinds of policies — and people — Trump tends to support.

The first Native American to hold the laureateship, Harjo recalls and laments the violence and displacement that has marked hundreds of years of Native American history: “The children were stolen from these beloved lands by the government./ … / …they were lined up to sleep alone in their army-issued cages.” She’s talking about Native American children forced from their homes in the 19th century, but it’s hard to imagine she does not also mean to call to mind the present horrors at the Southern border.

Harjo began publishing poetry in the 1970s and has many collections, as well as a memoir, to her name. She belongs to the Muscogee Nation, has won lots of the major honors available to an American poet, and lives in Oklahoma. Her poems are accessible and easy to read, but making them no less penetrating and powerful, spoken from a deep and timeless source of compassion for all — but also from a very specific and justified well of anger: “They kill what they cannot take. They rape. What they cannot kill they take.” They are white settlers, the soldiers pushing westward, forcing Native Americans from their homes, destroying their families and cultures. They are also us. “I returned,” Harjo writes, acknowledging this book’s act of imaginative memory, “to see what I find, in these lands we were forced to leave behind.”

The book opens with a long poem that blurs the distinction — to my ears at least — between historical Native Americans and contemporary situations where people are trying to cross borders into a new life. It then weaves through lyrics, songs, prose interludes, and meditations that mix history — the poet’s ancestor, the tribal leader and warrior Monahwee is a recurring character — personal recollection, and urgent calls for spiritual awakening and action: “Someone is always leaving/ By exile, death, or heartbreak,” she writes in “Break My Heart.” “Police with their guns/ Cannot enter here to move us off our lands/ Or kill our babies.”

Despite its many resonances with the present situation in America, this book was not written as a commentary on the Trump presidency: The horrors it recounts, and the hopes it upholds, were here long before — and will remain long after. This is an old and ongoing story in which “Even when I dreamed, I dreamed a chain around my neck.”

Harjo tells the tale of a fierce and ongoing fight for sovereignty, integrity, and basic humanity, a plea that we as Americans take responsibility for what’s been — and being done — in our names. Her work is also a stark reminder of what poetry is for and what it can do: how it can hold contradictory truths in mind, how it keeps the things we ought not to forget alive and present.

“What we speak always returns,” she writes, “With a spike of barbs/ Or the sweet taste of berries in summer.” We need — and deserve — both those barbs and berries right now.

Craig Morgan Teicher is the author, most recently, of the poetry collection The Trembling Answers and a collection of essays We Begin In Gladness: How Poets Progress.