There are two graphic novels out this summer about Jean-Michel Basquiat, and you’re definitely going to hate one of them. Which one? That’s harder to say. Julian Voloj and Søren Mosdal’s Basquiat and Paolo Parisi’s Basquiat: A Graphic Novel couldn’t be more different: Mosdal emulates the artist’s agitated lines, while Parisi uses flat zones of primary color, in the style of Basquiat’s mentor Andy Warhol. Aficionados will doubtless disagree about which book works—but that was probably inevitable. There’s something inherently odd about using one artistic tradition to depict the life (to say nothing of reproducing the work) of an artist from a different tradition. And yet, not only are a growing number of cartoonists creating books about famous artists, but their approaches are dizzyingly varied. When is a comic book a fitting tribute to an icon?

It’s a question that numerous publishers and creators are eager to address. Andy Warhol, Salvador Dalí, Jackson Pollock and Francis Bacon have all been memorialized in panel form in recent years. It’s not a stretch to use the quintessentially modern medium of comics to capture the life of a 20th-century artist; the free-flowing Niki de Saint Phalle: The Garden of Secrets, by Dominique Osuch and Sandrine Martin, is a particularly ingenious tribute to an underappreciated figure. But even Velázquez, Caravaggio and Goya are getting cartoon treatments.

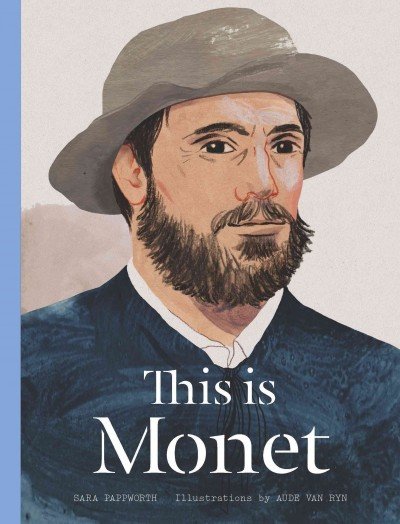

by Sara Pappworth and Aude Van Ryn.

The results of such attempts vary widely, but one rule is clear: Don’t reproduce the artist’s paintings if you can possibly get away with it. That’s the misstep of Monet: Itinerant of Light, by Salva Rubio and Efa. Efa envisions the world around Monet the way the artist would paint it, with vivid patches of light and dark dappling every scene. It makes for a beautiful book—that is, until you get to Efa’s recreations of Monet’s best-known paintings, which naturally suffer by comparison with the originals. In This Is Monet, on the other hand, illustrator Aude Van Ryn doesn’t attempt to duplicate her subject’s famous works. Instead, the book intersperses color plates of the actual paintings with Van Ryn’s drawings of scenes from Monet’s life. (In one particularly charming interlude, the Monet family helps to carry canvases in a wheelbarrow). Van Ryn’s style is complementary without being imitative—a tough balancing act that Efa doesn’t pull off.

This Is Monet is part of an unusual series from British publisher Laurence King that combines biographical text, reproductions and modern illustrations. “I wanted to be able to show, in illustrations, the pop culture that existed around the artists,” series editor Catherine Ingram says. “Even … Old Masters paintings, they’ve got a vibrant visual culture they’re tapping on. That visual culture is missing from art history books. It’s time to get back to that, to get the illustrators involved.”

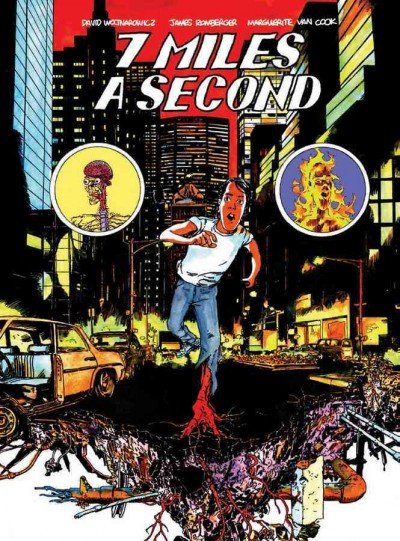

by David Wojnarowicz, James Romberger and Marguerite Van Cook.

Some corners of the art world have always embraced comics, of course. In 1988, David Wojnarowicz asked his friend and fellow East Village artist James Romberger to collaborate with him on Seven Miles a Second, an adaptation of Wojnarowicz’ autobiographical writings. Romberger, whose depictions of downtown New York life can be found in many museums’ collections, had to finish the book alone after Wojnarowicz died of AIDS in 1992. But he was aided by Marguerite Van Cook, who’d shown Wojnarowicz in her gallery, gone on road trips with him and had long discussions with him about color theory. Van Cook gave the book its explosive palette. (The book was reissued by Fantagraphics in 2013 and is now being self-published by Romberger and Van Cook.)

9(MDAxOTAwOTE4MDEyMTkxMDAzNjczZDljZA004))