Out of the 12 books chosen for the campaign, only one was written by a black author—The Count of Monte Cristo, by Alexandre Dumas.

“It’s still a story by a white author, featuring a white character, told via the white gaze,” McKinney says. “And none of this has changed within the contents of the story itself. They’re essentially just slapping a cover on it to ‘celebrate diversity.’ But a lot of us felt that you’re just trying to cash in on the fact that it’s Black History Month, and now all of a sudden, black faces and brown faces will sell books. Just maybe one, two years ago, people were saying in meetings, ‘Yeah, you can’t put black people on covers. It’s not going to sell the book.'”

Interview Highlights

On what Barnes & Noble could have done instead

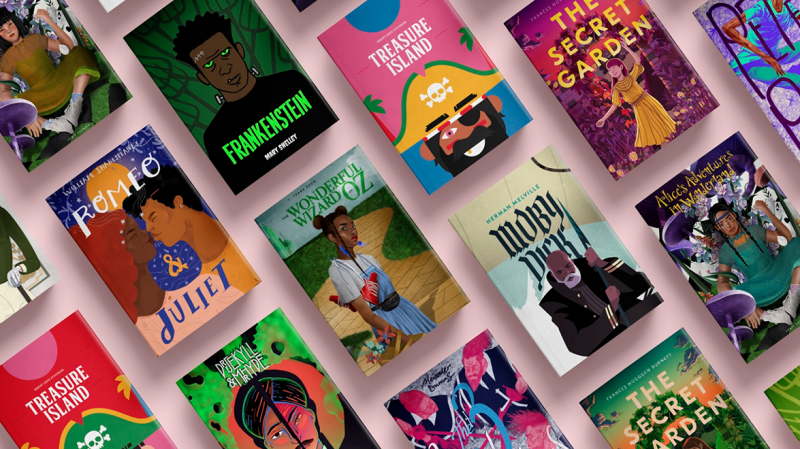

Feature black people, that’s the beginning and end of it. If you’re wanting to put a spin on classics, feature classics that are by black and brown authors. Like Zora Neale Hurston. Toni Morrison. Give their covers updates and put them on your tables. Or if you want to do this thing where you connect to the ideas of the classic canon, we are out there writing reimaginings and retellings and putting ourselves in the narratives of these stories. Like Pride & Prejudice. Like Alice in Wonderland. Like Wizard of Oz. We’re doing that, so feature those books if that’s the angle you want to go.

On diversity in book publishing

No one thinks they’re capable of making mistakes at this level. Especially mistakes like this. Because if you did think that that was a thing that could happen, you would have things in place and people in place to be able to prevent it from happening, right? I’ve been that person, you know, that one black voice, that one person of color in the room or maybe there are two or three of us who says, maybe this isn’t a good idea. But then we’re shouted down or talked over, so it rolls out. This definitely says that there were no people of color in the room to make those decisions. And if they were, no one listened to them.

On representation

I am of the camp of if you want good representation, you let those people speak for themselves. You set up the microphone, you check the levels, you get everything together, and then you get out of the way. Especially if you’re someone who has the resources to do that. And then we can take it from there. That’s what I think good representation is. It mostly comes from within the communities that are attempting to be represented because nobody knows it like us, right?

There are people who do do the work and they take the care and they show the research and they’re very sensitive to the nature, not only of the representation, but the context around the bad representation that has come before it. Cause you’re not just representing us in that moment, right? You’re fighting against this narrative that has been developed for decades and people don’t even take that into account. They’re just like, “Oh, well, you know, let me write this down and get this out there.” And maybe I don’t play into, you know, this sharp thing that people are aware of right now, but you miss the connotation of like maybe minstrelsy you know, from decades ago, that’s still very much felt in our community. So I think that good representation happens when we’re allowed to take the mic.

This story was produced for radio by Justine Kenin and adapted for the Web by Brianna Scott.

Copyright 2020 NPR. To see more, visit NPR.9(MDAxOTAwOTE4MDEyMTkxMDAzNjczZDljZA004))

9(MDAxOTAwOTE4MDEyMTkxMDAzNjczZDljZA004))