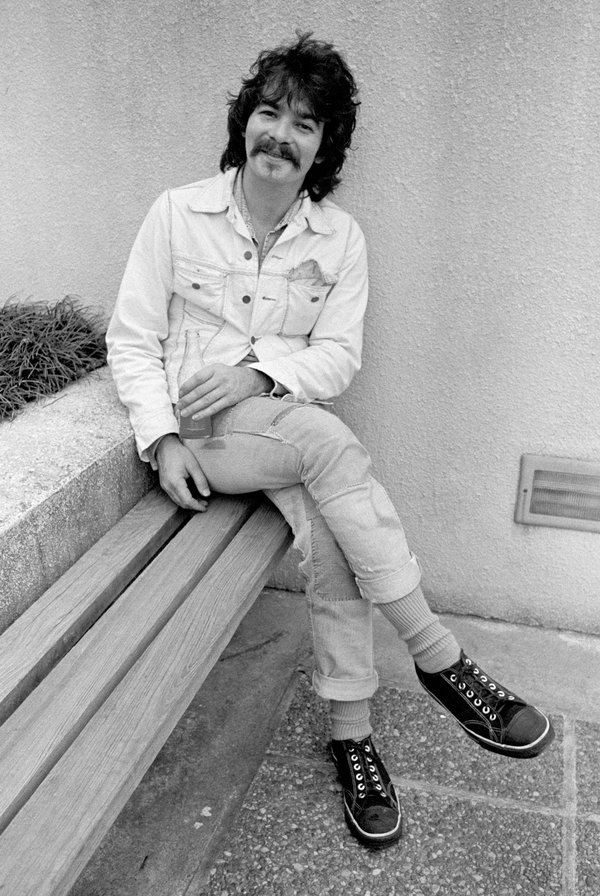

John Prine, a wry and perceptive writer whose songs often resembled vivid short stories, died Tuesday in Nashville from complications related to COVID-19. His death was confirmed by his publicist, on behalf of his family. He was 73 years old.

Prine was hospitalized last week after falling ill and put on a ventilator Saturday night, according to a statement from his family.

Even as a young man, Prine — who famously worked as a mailman before turning to music full-time — wrote evocative songs that belied his age. With a conversational vocal approach, he quickly developed a reputation as a performer who empathized with his characters. His beloved 1971 self-titled debut features the aching “Hello In There,” written from the perspective of a lonely elderly man who simply wants to be noticed, and the equally bittersweet “Angel From Montgomery.” The latter song is narrated by a middle-aged woman with deep regrets over the way her life turned out, married to a man who’s merely “another child that’s grown old.”

Bestowing dignity on the overlooked and marginalized was a common theme throughout Prine’s career; he became known for detailed vignettes about ordinary people that illustrated larger truths about society. One of his signature songs, “Sam Stone,” is an empathetic tale of a decorated veteran who overdoses because he has trouble readjusting to real life after the war. (Prine has said he based the protagonist around friends who were Vietnam War veterans, and also soldiers he encountered during his own two-year stint as an Army mechanic.)

Like “Sam Stone,” many of Prine’s songs also had an uncanny ability to address (if not predict) the societal and political zeitgeist. The understated 1984 song “Unwed Fathers” illustrates pernicious double standards pertaining to gender: The titular group “can’t be bothered / They run like water, through a mountain stream,” while the young women they impregnate are shamed and face consequences. Recorded for John Prine, “Your Flag Decal Won’t Get You Into Heaven Anymore” criticizes people who use piety and patriotism as a cover for supporting an unjust war — a theme he’d revisit on 2005’s “Some Humans Ain’t Human,” which pulls no punches slamming both hypocritical people and the Iraq War started by George W. Bush.

But like fellow songwriting iconoclast Shel Silverstein, Prine also cloaked his pointed commentary within whimsical wordplay. “Some Humans Ain’t Human” claims that inside the heart of these turncoats is “a few frozen pizzas, some ice cubes with hair and a broken Popsicle,” while “Dear Abby” has a lilting, rollicking rhythm to its verses, as it gently chides advice-column complainers to count their blessings. “Bruised Orange (Chain of Sorrow)” uses both absurdity (an altar boy struck by a train) and the mundane (a bench makeout) to encourage people to stay positive and have gratitude.

And “Christmas In Prison” boasts one of his best lyrics — “She reminds me of a chess game with someone I admire” — while embodying his quiet irreverence. “It’s about a person being somewhere like a prison, in a situation they don’t want to be in, and wishing they were somewhere else,” he wrote in the liner notes to 1993’s Great Days: The John Prine Anthology, adding that “I used all the imagery as if it were an actual prison. … And being a sentimental guy, I put it at Christmas.”

Prine was born on October 10, 1946, to parents with strong family ties to Paradise, Kentucky, a place that later served as the backdrop to “Paradise,” his cautionary tale about a coal country town destroyed and discarded by corporate interests.

9(MDAxOTAwOTE4MDEyMTkxMDAzNjczZDljZA004))