At the center of the documentary, at the center of the Bulls, and in some ways at the center of the world, especially circa 1993, is Michael Jordan. Jordan has always somehow been both ubiquitous and a little elusive. These are by far the most involved, seemingly candid interviews I’ve ever seen with him; he gave the filmmakers a lot of time to talk about everything from his tensions with Isiah Thomas to the death of his father.

Incidentally, the bad blood between the Bulls and the early ’90s Detroit Pistons—Thomas especially—is one of the juiciest tales that arises from the first years of the Bulls’ dominance. Some examinations of old sports rivalries show former athletes burying the hatchet or at least finding some humor in their pasts (as in the outstanding 30 For 30 entry Winning Time, about the Pacers and the Knicks). This is not that kind of documentary. Jordan doesn’t seem to have lost an iota of his disdain when it comes to Thomas, and the filmmakers offer some artfully presented evidence that he’s got good reason to remain frustrated.

The interview techniques here are very smart; I especially like the decision to sometimes let an interview subject see the footage of what someone else has already said. Sometimes you get a wry “that’s about right”; sometimes you get a laugh; sometimes you get Jordan roundly ridiculing another player’s reminiscence of perhaps having gotten the better of Jordan once, just for a moment. He assures you that never happened. Never.

In fact, one of the most compelling threads in The Last Dance is the fine line between Jordan’s unmatched competitive drive—to which everyone attributes much of his success—and his extreme sensitivity to slights. Even at the height of his powers, he cannot bear to have anyone even casually compared to him, in any way, lest his uniqueness be bruised. Over and over, he explains that his desire to win a particular game came from a need to retaliate following something inadequately reverent that was said about him or the Bulls. (This at a time when he was also exhausted by the demands of being as famous as he was.) He attributes one of his best performances to wanting to get back at someone who didn’t greet him at a restaurant.

Did Michael Jordan, who could have crushed most of his enemies in multiple ways at any time, actually need to make things this personal in order to be motivated, as he seems to suggest? Or was he just an outstanding basketball player who also nursed decades of grudges because it’s just how he is? Do you need resentments to be that good?

It feels important that The Last Dance doesn’t seem built to change anyone’s opinion of Jordan, for better or worse. It returns again and again to his extraordinary talent, his legendary work ethic (including during his stint in minor league baseball, which took place between the Bulls’ two three-peats), his closeness with his family, and his version of leadership—which looks a lot like bullying, but which teammates who are interviewed generally insist was for the best.

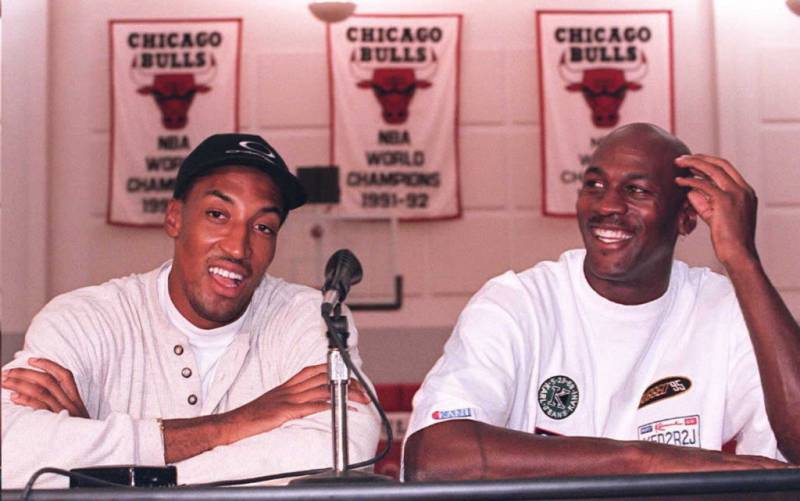

But there’s also a lot of time spent on the fact that no matter how good Jordan was, and no matter how much talent he had, he was never going to win six championships without the rest of his team. In that final season, when Pippen—who everyone then agrees is wildly underpaid because he got into an ill-advised seven-year contract—decides to have surgery on his foot at the beginning of the season rather than getting it over with in the off-season, in part because he feels stung by management’s unwillingness to renegotiate, Jordan is irate. Pippen has left him out there to fend for himself, he complains. He has disappointed the team. Indeed, the season doesn’t start off well at all.

And … well, wasn’t this Pippen’s point? Wasn’t he precisely trying to demonstrate that he was needed more than they were treating him like he was needed, even with the great Michael Jordan on board? And didn’t he prove he was right? This, too: Couldn’t Jordan have thrown his massive influence behind Pippen’s request for a renegotiation as he had behind Phil Jackson, announcing he’d quit if the coach was replaced? It’s not explicitly explored, but watching Jordan get so angry that someone else was also trying to have his value recognized is, at times, curious.

The biggest open question from The Last Dance is what it would take to put together a team this dominant over this period of time again. Could you possibly keep guys together long enough? If a Scottie Pippen doesn’t get into a bad seven-year contract (a mistake you have to assume young players want to avoid) that lets the Bulls keep him cheaply, does Michael Jordan get the support he needs to be Michael Jordan in the first place? Put another way: No matter how good LeBron James is, it seems like he was probably never going to win six championships in eight years with the same team.

9(MDAxOTAwOTE4MDEyMTkxMDAzNjczZDljZA004))