Julia Morgan’s name might not be familiar to everyone, but some of the beautiful landmarks she left behind undoubtedly are. Hearst Castle in San Simeon stands as the most famous monument to Morgan’s boundless imagination—but across the Bay Area, her architectural fingerprints dot the landscape.

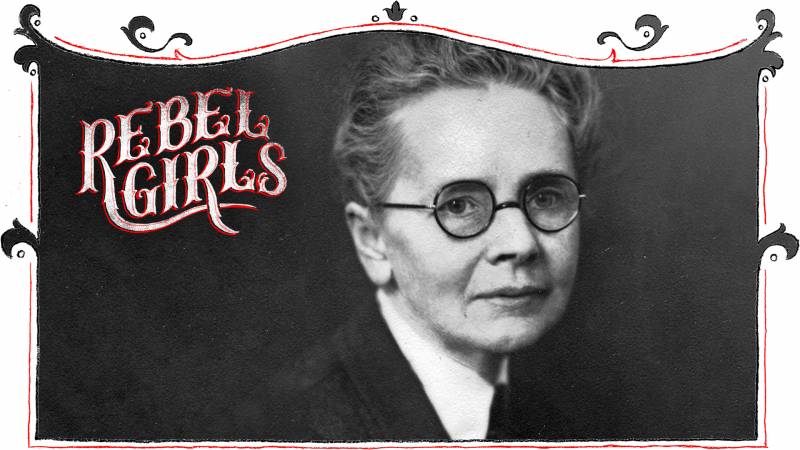

Born in San Francisco in 1872, Morgan understood how to create grand and imposing structures without once sacrificing meticulous detail. It was a combination that forced the world to look past her gender—she was California’s first licensed female architect—and simply embrace her abilities. Her talent, coupled with a willingness to work around the clock, six days a week, made her prolific. In the first 12 years of her career alone, she completed 300 commissions, some of which were extremely prestigious.

Just four years after receiving her architectural license, Morgan was tasked with rebuilding the lavish (not to mention enormous) Fairmont Hotel in San Francisco’s Nob Hill. The hotel had been destroyed by the 1906 fire and the owners wanted to rebuild using the safest possible methods. They had no choice but to turn to Morgan: She had knowledge of reinforced concrete, a brand new technique, that other California architects lacked at the time.