When I was in college, my girls and I would get all dressed up in our tight jeans, jersey dresses and stretchy shirts, and line the hallway of the designated “Afro floor” dorms at UC Berkeley, ready to go to a party. That hallway was like a runway. New fits were debuted, uncomfortable stilettos were broken in, fresh perms and presses ready to be sweated out. We were Black girls in search of fun nights, backed by the sounds of Bay Area hip-hop that filled the venues with a kind of euphoric chaos that I haven’t witnessed since.

For Filmmaker Nijla Mu’min, Loving Bay Area Hip-Hop is Complicated

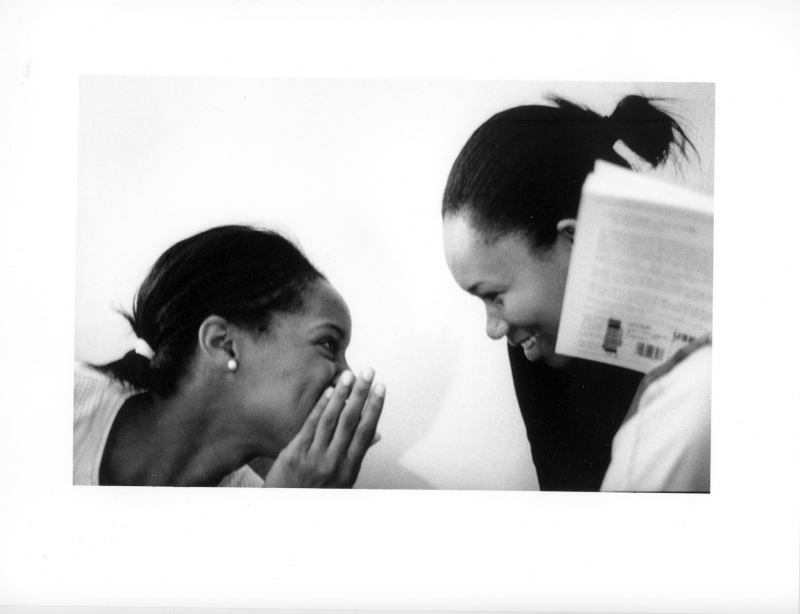

We never drank at these parties, but the dancing was a kind of intoxication. We danced until we sweat, forming a circle together; young Black women mouthing the words to songs not always meant for us, transforming meaning as our hips circled and swayed in the darkness. This was our space.

The guys came in white T-shirts and button-ups, some with deep waves in their haircuts, smelling of strong cologne. And we didn’t have to try. We’d just turn around, and they’d be there, standing behind us, waiting to be grinded on. But what if we didn’t want to? What if our bodies weren’t an invitation?

One night, I refuse to dance with a guy who then picks me up and carries me around the club in anger. I struggle to get down but he won’t let go. My girlfriends tug his arm until he does. I remember.

Another time, “Shake That Monkey” by Too $hort and Lil Jon comes on and my knees are tired. I wanna hit up Jack in the Box, but my girls are still dancing. Some guy keeps getting behind me, and it seems like he might be aroused through his jeans. I can feel his wet breath on my neck. I’m uncomfortable, and I quickly dance away from him, disappearing into the crowd as the song segues into an extended chorus of, “Now put your ass on his dick / Let him know you the baddest lil’ bitch / Put your hand on your clit / Ask him do he like that shit.”

I made my first short film in 2006. It was around the time that E-40’s classic “Tell Me When To Go” was released. I had a white Cutlass with a blue interior that could’ve been a scraper, and the bass bounced off the windows. My film was appropriately titled Oakland, about a Black woman falling for a Black man through her bedroom window. It starred my friend Yahya Abdul-Mateen II. My editor used that song during one of the opening scenes in the film. We shot on-location around the North Oakland house I lived in at the time. One day, while I was filming b-roll in my neighborhood, a Black male neighbor yelled out: “Bitch, you better put down that camera!” It made me aware of myself in a way I hadn’t been before, and I began to realize I wasn’t always perceived as an equal participant in the culture I came to celebrate.

While we could all dance and go crazy at the parties, I was called an “ugly ass bitch” on Telegraph Avenue for not giving my number to a man I didn’t know. I walked away startled, with anger and hurt in my throat. I was followed by a different group of men while driving home because I wouldn’t slow down to talk to them through my car window. I was writing for a Bay Area hip-hop publication and was told I couldn’t interview a well-known Bay Area rapper because he didn’t like to be interviewed by “females.” And I remember a friend who got spit on by her boyfriend in high school because she had an argument with him. We often celebrated the pimp culture in this music, sometimes at the very expense of ourselves.

My identity as a Black woman filmmaker was forming at this time, and it was inherently subversive. I wanted to document the people around me in ways that humanized them, especially Black women. The heavy thump of “Tell Me When To Go” was like the backdrop of my emergence into this medium. I was going dumb at the parties, spending long days in the dark room developing film prints and then renting cameras to bring the Bay to life at a time when I had no example to follow.

That same independent, grassroots, guerrilla grind culture that helped birth some of the classic Bay Area hip-hop is what also brought me into storytelling in this medium. I wasn’t selling CDs out of my trunk like E-40, but I was teaching and immersing myself in the craft, documenting the sounds and moments that would come to define an era. I was gettin’ it. I was a Black girl—discovering, but not always welcomed.

I wonder how certain Too $hort songs have aged, and if they will be played in his Verzuz battle with E-40. I wonder if we’ll all just bob our heads and let it ride. I wonder what it means to be of a moment, but also be critical of your place in it. Those Friday nights dancing, those days building stories with a camera and film, are indelibly a part of the culture I come from, though I see things through my own lens.