William T. Wiley had many names over six decades as an artist. There were his alter egos Mr. Unatural and Zenry. Critics called him the Zen Cowboy, the Metaphysical Funk Monk, the Dude Ranch Dadaist and Huckleberry Duchamp—handles that conjured California’s brew of folly, spirituality and rugged individualism. Few other West Coast artists inspired so many nicknames. One could chalk this up to Wiley’s thick mustache, blue jeans, boots and bolo tie. But there was something more elusive that aroused the image of a folk hero—and that needed some kind of special name. He worked against the grain in a way that was knowingly oblivious, like someone slightly out of time or in possession of ancient wisdom. For many he was a sort of art world frontiersman, tucked away in the hinterlands of Marin County. He died on April 25, at age 83, due to complications from Parkinson’s disease.

Remembering William T. Wiley, Bay Area Artist, Teacher and Notorious Punster

I met Wiley for the first time at his studio in late 2019. I was struck first by his wit, which came in flashes that were easy to miss. And I was lured in by his easy manner and long, comfortable pauses. One wall of his studio was reserved for works in progress. They were delicate black-and-white paintings that belied the tremors of Parkinson’s. The other walls were festooned with objects, among them a clock set in reverse with its numbers printed backwards, a painter’s palette bedecked with an infinity sign, a map of Indiana, a punning holiday card (Happy You Near!) and a portrait of Jim McGrath, Wiley’s high school art teacher. They reminded me of the mementos and inside jokes that populated so many of his paintings.

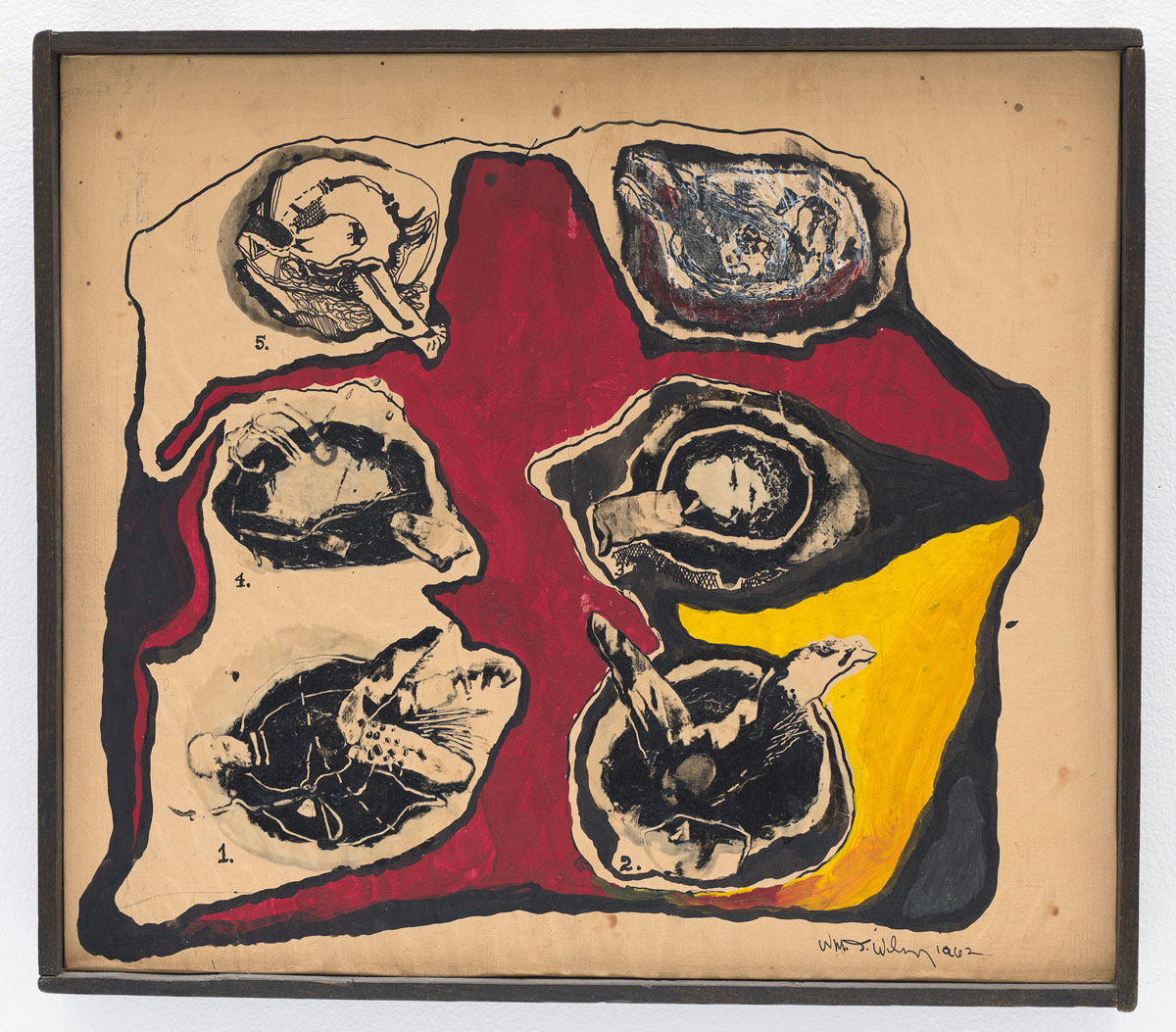

William T. Wiley was born in Bedford, Indiana in 1937 but didn’t stay for long. The Wiley family hit the road every year so that his father could find new work as a foreman, a surveyor or a service station owner. “Fifth grade in Washington, sixth grade in Texas, seventh grade in California,” is how Wiley remembered this time. Eventually they settled in Richland, Washington, where he attended high school and worked construction in the summers. Themes of wayfaring and blue-collar Americana would emerge years later in Wiley’s work, but when he left Richland in 1956 to study at the California School of Fine Arts (now the San Francisco Art Institute), abstract expressionism was the order of the day. Instructors Elmer Bischoff and Frank Lobdell transformed Wiley into a painter of vigorous blotches and skeins, and after receiving his masters in 1962 he shot to national recognition through exhibitions at the San Francisco Museum of Art and the prestigious Allan Frumkin Gallery.

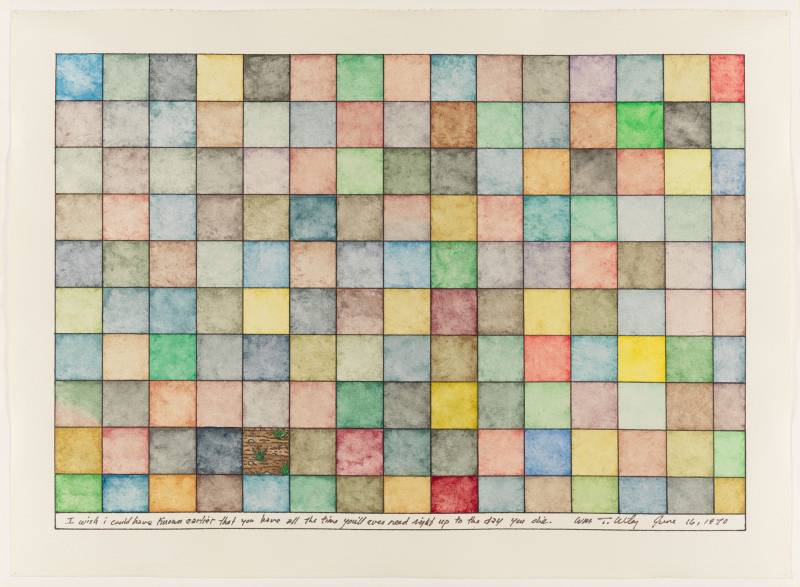

He soon, however, had enough. In 1967 Wiley was already burned out from the demands of the art world and in need of a new spark. A simple realization reignited him, something almost too obvious: make art without thinking too much about it; use what first comes to mind. “It suddenly occurred to me,” he later said, “that art was about what I’d heard on the radio that day, or something I saw outside.” A series of watercolors ensued that sponged up little things from the world around him: the tools in his studio, messages from friends, headlines from newspapers, passing thoughts. O.T.P.A.G. became a motto—an acronym for “on the page anything goes.”

Wiley’s stream-of-consciousness is both bewildering and easy to enjoy. This is his curious feat. Enigmatic references and symbols (why are there always infinity signs, checkered squares and question marks?) confound art historians, and yet children rejoice at the twists and turns of his compositions. Puns, homonyms, and spoonerisms abound. Words and images crowd together to make their meaning impenetrable, but their exploration is gratifying. It’s personal, amusing and oblique all at once.

Wiley’s most lasting influence might be his many years teaching at UC Davis. With Roy De Forest, Manuel Neri, Mike Henderson and Robert Arneson, he transformed a school best known for its agricultural program into ground zero of the so-called “Funk” movement. Funk was loose, kitschy and unafraid of ugliness. Few agreed on the precise meaning of the term, and many artists rejected it outright, but for Wiley it simply meant “down home.” It was rough around the edges and done for its own sake. As Wiley wrote, “Don’t be afraid of being right or wrong about art … the art won’t mind … be afraid of not feeling very much.”

Zully Adler is a PhD candidate at the University of Oxford and former Shorenstein Research Fellow at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. William T. Wiley’s work can be seen in ‘Con-Fusion-Ism: The Art of William T. Wiley’ on the fifth floor of SFMOMA.