Nguyen’s embrace of indeterminability is evident in the anthology itself, which takes the form of a kind of montage; a choir of voices placed in kinetic proximity. Writers, artists and poets are bound together in the pages like threads in a spider web. Authors in one section reference works written by other contributors, netting a space for shared attention and providing a transcript of collaboration.

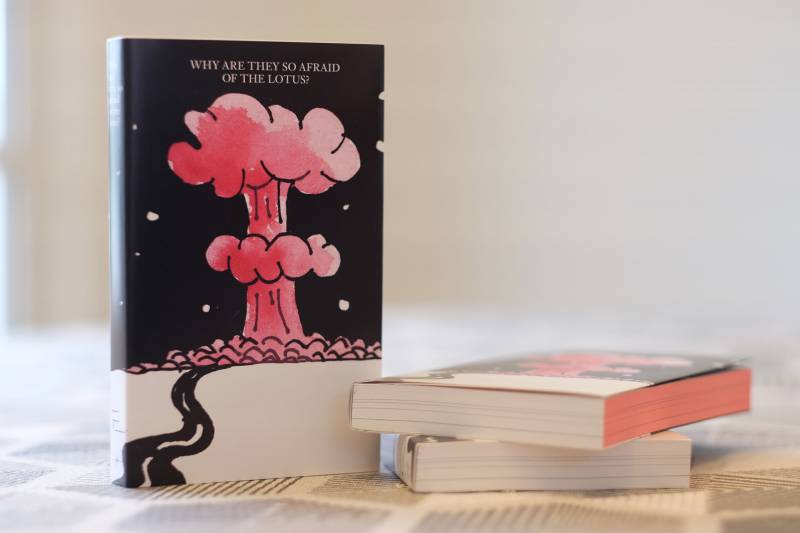

In the filmmaker Sky Hopinka’s “The Center of Somewhere,” a meditative text on his relationship to Indigenous representation as a member of the Ho-Chunk Nation of Wisconsin and a descendent of the Pechanga Band of Luise Mission Indians, Hopinka writes, “What is urgent is what exists beyond myself and my experience.” Expanding that thought, he considers that his sense of self comes from “many threads being woven together to attempt to form and ritualize something less clear.” This sentiment, which could easily be a line from one of Trinh’s films, feels like a guiding parameter for how to read the anthology. Why are they so afraid of the lotus? makes its statement through correlated texts rather than a single given thesis.

Fred Moten considers the montage as a radical technique for putting images in dialogue with each other in his book In The Break. He invokes an idea of Trinh’s, “the multiple Oneness in Life,” that she introduces to speak to the complexity of her own identity as it is re-conferred across languages, nationalities, and social spaces.

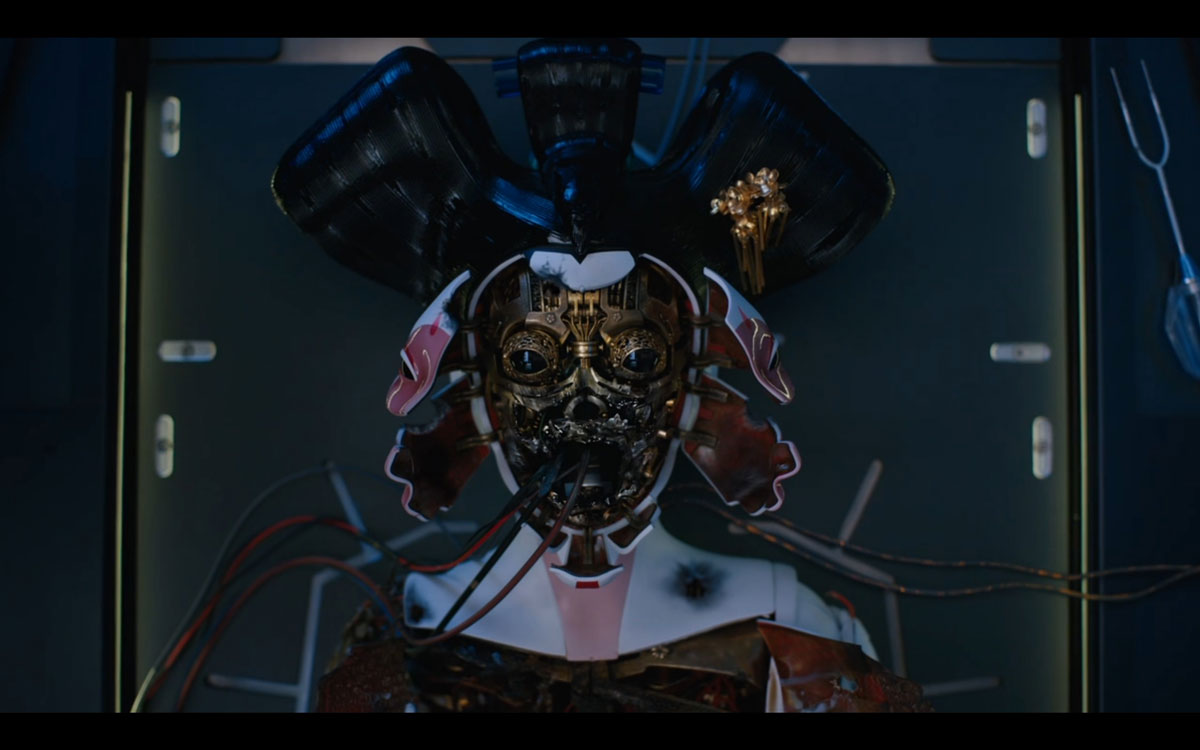

In a 2019 talk entitled “Lovecidal,” which Trinh gave at the Wattis, she introduces the idea of “vernacular architecture,” which, she puts poetically, ‘breaks within here and there.” Vernacular architecture feels like the right name to use to describe Renee Gladman’s Paragraphs. Skeletal drawings, at once image and text, function between architecture and scribble. Each image-poem is made up of language that inhabits its physicality fully, and, if considered with Trinh’s thinking, insists on opening up a liminal space that still resists permanency. Gladman’s drawings are neither here nor there.

Trinh has written often about the diasporic experience, as a Vietnamese person living outside the country for most of her life, and how it relates to a sense of time. The feeling of displacement, of being out of context, has an eerie relevance during the pandemic, as for the past year everyone in this country was asked to make alienation routine. Public space in the Bay Area transformed dramatically. New access and new barriers punctuate the city, and both the capacities and limitations of convening digitally loom over social gatherings.

“What use is you and me together in a room?” Steffani Jamison asks, rhetorically, in her piece on Lorraine Hansberry’s “What Use are Flowers?” which expands on Hansberry’s eponymous unpublished story, in which a hermit survives the end of humanity and finds himself in the peculiar position of trying to describe the utility beauty once held to the planet’s few surviving children.