“It’s actually scientifically proven you’ll make more money on an independent label if you’re a not-so-great punk band like us,” Jawbreaker singer and guitarist Blake Schwarzenbach once told an audience in 1993. This, he said on stage, isn’t an empty play to the crowd, but rather good business advice. “The smart money stays on an independent, and actually gets richer. And you can do it scrupulously. So think about that.”

Not long after, Jawbreaker would sign a nearly million-dollar record deal with the label Geffen.

And they weren’t the only ones. Immediately following the massive boom that was Nirvana, major labels began scouring local indie punk scenes looking for the next big thing. But if you were the kind of band that earned its cred giving the finger to corporate suits, how were you supposed to navigate shaking their hand for your shot at rock stardom?

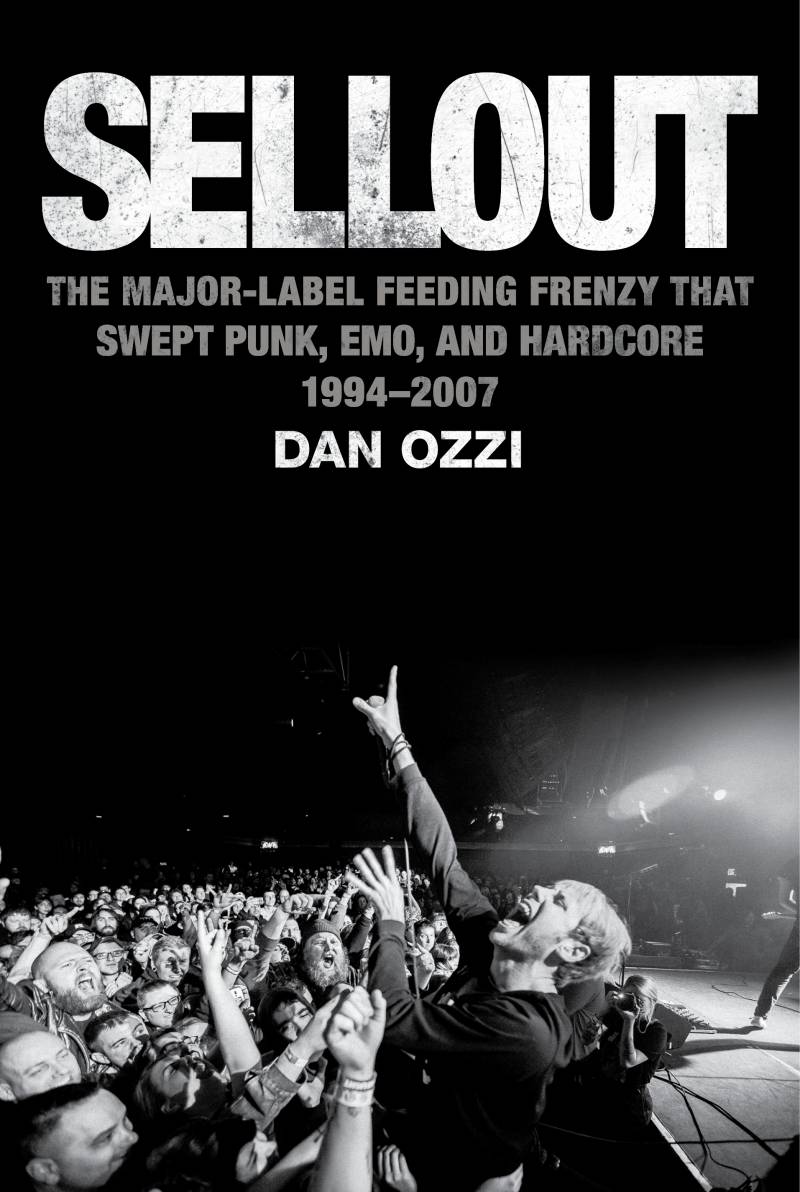

That’s the question at the center of the new book Sellout: The Major Label Feeding Frenzy That Swept Punk, Emo, and Hardcore 1994 — 2007 from music writer Dan Ozzi. The book uses the major label debuts of 11 bands to examine a music industry in flux, fans feeling betrayed, and bands just trying to navigate the machine. “I wanted to know, what happens to the real people,” says Ozzi. “Is it worth it?”

Some chapters are straight-ahead success stories (Green Day, Blink-182, My Chemical Romance). Others, less so. Which brings us back to Jawbreaker.

9(MDAxOTAwOTE4MDEyMTkxMDAzNjczZDljZA004))