In The Exterminating Angel (1962), one of the signature satires by the sublime Spanish surrealist Luis Buñuel, the mannered façade of upper-crust guests at a tony Mexico City dinner party cracks and crumbles when the servants depart. Helplessly left to feed and fend for themselves, and oddly incapable of leaving the premises, the masters and mistresses of the universe revert to behaving like animals.

Jean-Pierre Jeunet’s ‘Bigbug’ is the Anti-‘Blade Runner’

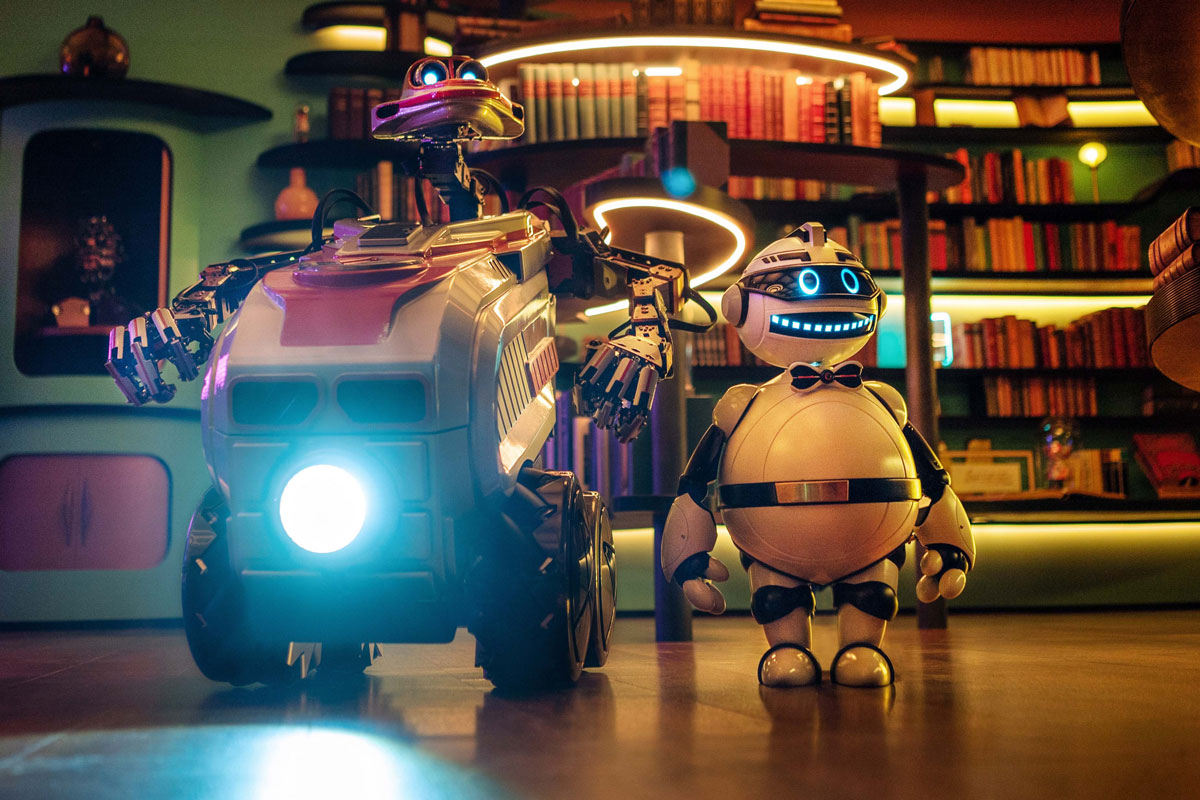

French filmmaker Jean-Pierre Jeunet’s fast-paced, multicolored and wildly entertaining Bigbug reimagines this scenario, with a good deal less acidity and more empathy, in 2045, when robots are the low-status household help, everything is Alexa-ized and the next-level generation of machines has designs on displacing (or rather, colonizing) the human race. The scene isn’t a dinner party but an ordinary day in a suburban house, complicated by the unexpected arrival of the ex-husband and his young squeeze—and further complicated when the trio of smart “home appliances” decide to lock the extended family and friends indoors for their own safety.

Bigbug (a worldwide Netflix production that premiered this past Friday) is the anti-Blade Runner, a gaudily art-directed and cheerfully tongue-in-cheek fantasia of post-apocalyptic life on earth. It’s concerned with the same fundamental question, though: What is the ineffable quality that makes us human, and lies beyond the ken of robots and androids?

Jeunet is the co-writer, director and architect of the much-loved hit Amélie (2001) and The Very Long Engagement (along with ’90s cult faves Delicatessen and The City of Lost Children). Those later films provoked a love-it-or-hate-it response, you may recall, with the haters turned off by the reek of sentimentality perfumed with nostalgia. We’ll always have Paris, or at least the Paris snow globe of Amélie.

I fully expected Big Bug to pine for a romanticized past of scratchy Édith Piaf LPs and crêpes with strawberry preserves (homemade, of course). And while the lady of the house cherishes the long ago (she has a large collection of books, and at one point models the character of Garance, the object of everyone’s desire in Marcel Carné’s immortal Les enfants du paradis), Jeunet keeps the focus on the timeless impulses of human nature—lust, jealousy, pride, innovation and the need for connection, companionship and love.

That final bit involves the Spielbergian reconstitution of the nuclear family, the last in a very long chain of homages and send-ups of films by Jacques Tati (the cloned dog), Stanley Kubrick (HAL 9000, the most charismatic character in 2001: A Space Odyssey), George Lucas (R2-D2 and C3-PO) and no doubt many more that I missed. Jeunet’s affection for previous cinematic depictions of futuristic technology is palpable, but so is his concern for the quality of real life with actual, existing tech. As the teenage daughter says to the screen-savvy fella also stuck in the house, “When you’re purely virtual, how are you going to kiss girls?”

The pastel palette and frothy banter—I would say that Bigbug resembles a live-action cartoon except that gives short shrift to the game-for-anything actors, in particular Claude Perron as the bewigged robot cook/housekeeper Monique—camouflage but don’t obscure Jeunet and co-writer Guillaume Laurant’s social commentary. The reality show that resurfaces on the big-screen TV from time to time makes humans the humiliated targets of robot-torture, a kind of metaphorical revenge for our mistreatment of animals as well as our indifference to the degradation of the environment.

Much lighter, but just as pointed if you’re paying attention, is the stream of throwaway jokes. We’re informed in passing that that teen girl was adopted when the Netherlands flooded. By the time you’ve parsed the joke, which references rising ocean levels due to climate change while evoking Westerners who adopted babies after past quakes and famines in Asia and Africa, another three one-liners have zipped by.

Between its dense set design and rapid repartee, along with the necessity of speed-reading subtitles if you aren’t a French speaker, Bigbug demands and rewards a second viewing. (Though not right away, perhaps.) And that, arguably, is the lone advantage of its exclusive release on a streaming platform. Bigbug deserves to be seen on the big screen, and I’ll hold out hope that one day Netflix and the Castro will grant that wish.

For now, I’ll be content with the explicit Buñuel homage that Jeunet lovingly included. The erstwhile seducer (played by Stéphane de Groodt) of the lady of the house (Elsa Zylberstein), who’s stymied at every turn, has a goatee. His resemblance to Fernando Rey, the urbane and sexually frustrated lead of That Obscure Object of Desire and other Buñuel masterpieces (as well as the titular figure of The French Connection), is intentional and wonderfully satisfying.

‘Bigbug’ is streaming on Netflix. Watch it here.